We take so much for granted today about printed books. The wisdom of the ages can be captured and preserved for costs that are so low as to almost negligible. Save for the surfeit of information that currently exists, the modern man has no excuse not to be reasonably acquainted with his heritage.

It was not always so. Before the advent of the printing press, books circulated in manuscript form. They had to be copied by hand, and this was laborious and costly. In the ancient world, manuscript books were relatively cheap and plentiful; but papyrus became unavailable from Egypt during the Middle Ages, leaving expensive vellum as the only available medium for “mass” writing.

Our classical heritage–the literary monuments of Greece and Rome–was in a confused and sorry state before the age of printing. Only wealthy men, scholars, or churchmen owned books; literacy was the exception rather than the rule.

It is only by appreciating this backdrop can we begin properly to honor the greatness of a rescuer of classical antiquity named Aldus Manutius. His given name was Teobaldo Manucci. He was born at Bassiano in the Romagna in 1450, showed an early aptitude for language learning, and absorbed Latin and Greek readily. One of his students was the great Pico della Mirandola, who invited Aldus to tutor his two nephews. He must have been charming also, for he somehow managed to convince the mother of one of the nephews, the Countess of Carpi, to finance Aldus’s idea for a new publishing company.

It was an incredible plan, breathtaking in its conception and audacity. Aldus intended to publish, at a reasonable price, all that was important in Latin and Greek literature as then could be found. We must remember that, at this time, manuscripts were scattered all over Italy and the rest of Europe. Many of them were corrupted by careless monkish errors over the centuries, and differed substantially from one another. Someone would have to collate hundreds of arcane manuscripts and edit them, while trying to preserve their fidelity to the original, as far as this was possible. Qualified scholars would need to be hired who could collect, collate, and edit the codices. New typefaces in Greek and Latin would need to be cut by the printer.

Massive amounts of high-quality paper would need to be imported (no easy feat in those days). A purchasing public would have to be created where none previously existed, for classical learning in those days was not at all common knowledge. Most perilously, there were at that time no copyright protections. A printer might have to invest massive amounts of money to produce something of worth, only to see it quickly pirated in another European country.

We thus begin to glimpse the greatness of Aldus and his incredible labors. There were some advantages that he had. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Turks meant that a large number of Greek scholars had become refugees in Italy, especially Venice, which had long been a trading city. These men were idle and welcomed a task that appreciated their education.

Venice itself had become a center of publishing in Italy. Of the 5000 or so books published in Italy at the end of the fifteenth century, more than half (2835) came from Venice; the rest originated from printers in Florence, Milan, and Rome. Aldus was established in Venice by 1490.

At first he concentrated on publishing Latin and Greek grammars. These preliminary warm-ups done, he dove into the ocean. Employing a tribe of scholars, he attacked his task. He conversed with them readily in ancient Greek. Edited and illustrated editions of the Greek classics were produced, one after the other, a cascade of literary brilliance: Plutarch, Pindar, Euripides, Herodotus, Thucydides, Plato, Hesiod, and the rest of the pantheon.

Only one who has labored over and translated such works can fully appreciate the magnitude of the scholar’s commission. It was a revelation to the public, which had never seen such things before. In the span of a few years, the best heritage of the West was made available to all.

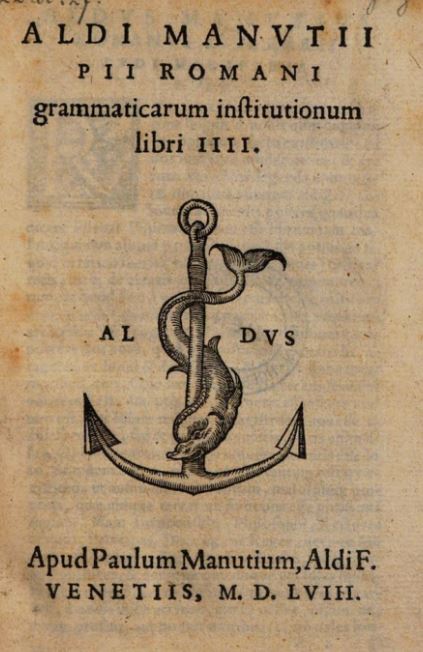

Even the great humanist Erasmus came to visit Aldus and help him produce an edition of his famous book Adagia. It was he who invented the font we now call italic. The motto of the Aldine Press–his publishing house–was Festina lente, which means, “Make haste slowly.” The symbol of his press (what we now call the publisher’s colophon) was a dolphin twined around an anchor. This combination, which can be found on old Roman coins, was intended to juxtapose stability and agility.

He nearly wore himself out with work, but he was a man on a mission. He would not be deterred by anything. Over the door of his publishing house he had inscribed this warning: “Whoever you are, you are requested by Aldus to state your business briefly, and to leave promptly…For this is a place of work.”

This was a man with no time or sufferance for fools.

He also founded what he called the New Academy in 1500, a society of scholars dedicated to the revival of Greek learning. He faced many difficulties. Political instability, war, strikes, labor shortages, and other interruptions were present, then as now. He did receive some patronage from Venetian authorities, but it was not a huge amount. By and large he had to finance his labors, and pay his scholars, himself.

He did not reap vast profits from his labors except in gratitude and glory. Almost as soon as his editions left the presses, they were pirated in Germany or France, often in inferior editions. But at least, he told himself, classical learning was being distributed. He could claim the satisfaction that comes from the knowledge of having a unique role in the order of things.

Let us never take learning and the preciousness of knowledge for granted. In every age and in every nation, there have been those who have labored, fought, sweated, and bled to produce or preserve the wisdom of the ages. The only reason that modern libraries of the classics exist today–the Penguins, Loebs, Bude, and Teubner editions–is because of one audacious Venetian who loved these old books so dearly. By his passion and his perseverance, he seeded Europe with the timeless tree of classical learning.

And so we here salute Aldus, and express our debt of gratitude.

Read More: Talent Applied Consistently Is Never Wasted

You must be logged in to post a comment.