Some books are so good that they become adopted by cultures outside their place of origin. Such a book is the collection of stories and fables that has found a home in India, Iran, the Arab world, and in Europe. The book is known by many names in all of these cultures, and various version of it exist, just as we find in Aesop’s Fables or the tales of the Thousand and One Nights.

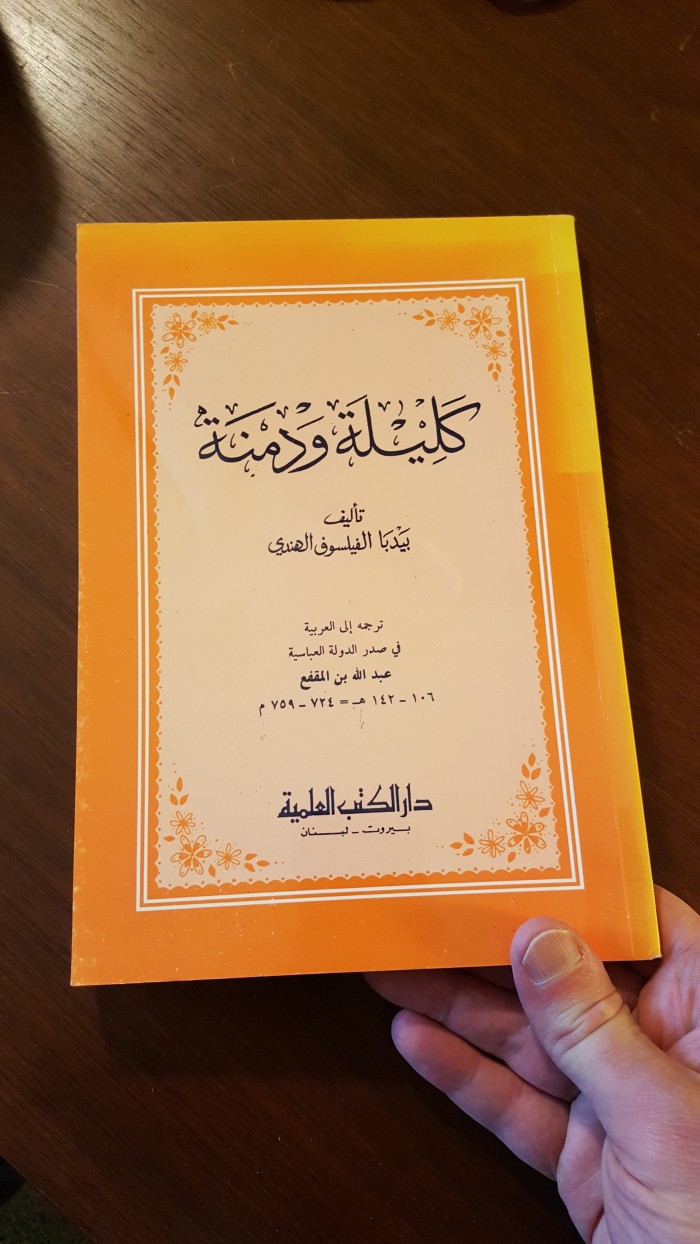

It is known most commonly in India as the Panchatantra, in Iran as the Kalīleh o Demneh, and in the Arabic-speaking world as كليلة ودمنة (Kalila wa Dimna). In Europe the book generally is known either by its Arabic title or by the generic Fables of Bidpai.

The book’s original form is of great antiquity. We are told that it first took definite shape around 300 B.C. under the authorship of an Indian scholar named Vishnu Sharma. Like many such collections of stories, he likely based his version on the oral and written traditions that he found at the time. From this point, the book found an eager audience. It was translated into Pahlavi (Middle Persian) by the scholar Borzuya around 570 A.D. In 750 A.D., it found a home in Arabic literature with the translation of Ibn Muqaffa, which he gave the name Kalila and Dimna.

From this point, the book found its way into Europe through Latin and vernacular versions that trickled out of Moslem Spain from 900 A.D. to about 1400. Alfonso X of Castile ordered it translated from Latin into Castilian Spanish around 1260. He was an urbane and worldly man, noted for the prominent roles he gave in his court equally to Christians, Jews, and Moslems. Rarely has a book had such a multitude of fathers, or spawned so many children. All in all, it has seen about 200 translations into over 50 languages.

What are the contents of this little book?

It is a collection of teaching-stories told using animals as substitutes for humans. The basic themes of the book, that run through all the tales, are the ideas that one must (1) cultivate friends; (2) truth will find a way of coming out; (3) intelligence is more important than force; (4) wise reflection is better than rash, intemperate judgment. We are provided a succession of tales about how to live with wisdom, and how to profit from diligence.

It almost reads like a digest of advice given by a courtier for a prince or a sovereign. And this is what I suspect it was intended to be, at least when Ibn Muqaffa produced his version. One gets the sense that Ibn Muqaffa was a figure like Niccolo Machiavelli, a former diplomat or advisor who suddenly found himself out of favor. His book may have been an attempt to offer his services to the sovereigns of his era. Unfortunately, he could not resist the temptation of getting involved in court intrigues. This failing ultimately led to his execution around 756 or 759 by the local authorities of Basra, Iraq. He thus failed in winning the favor of princes, but, nevertheless, won over all of posterity. Fate is not without a sense of humor.

My own familiarity with this great work is with the Arabic version written by Ibn Muqaffa. As written by him, it is a sublime and beautiful work of art. His Arabic makes use of rhyming prose, brilliant turns of phrase, and he packs his paragraphs with profound aphorisms.

It rises above the status of simple translation, and becomes a work of literature in its own right. Every student of Arabic should know this book. Kalila wa Dimna (in one version or another) is practically a standard textbook for beginning students of Arabic literature. Ibn Muqaffa’s original classical Arabic version is not an easy read, however. I remember my own frustrations when wrestling with his text. Many of the words are archaic, and require frequent trips to the dictionary.

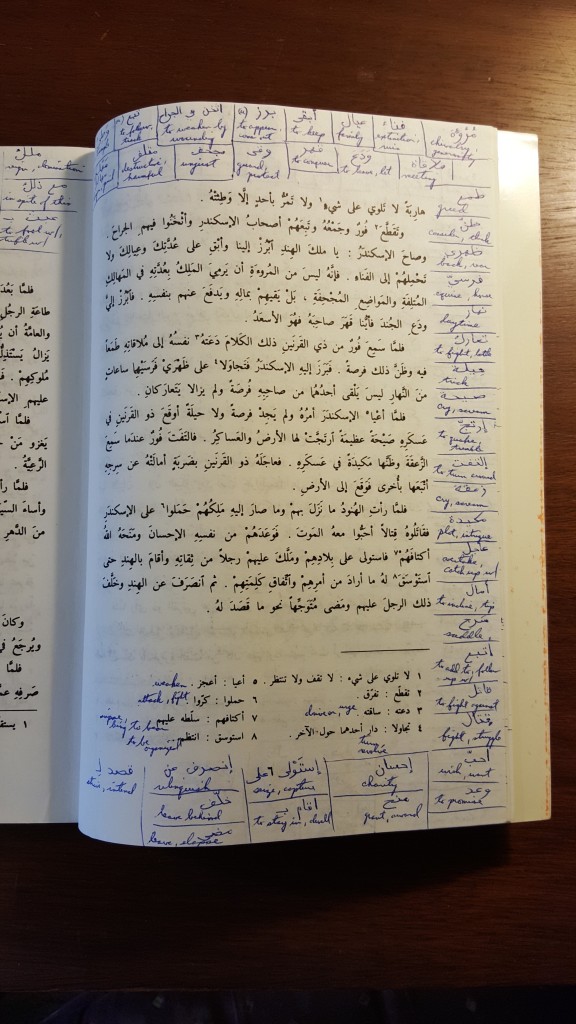

I still have it, and it is still cluttered with the notes and annotations of an enthusiastic student grasping for the meanings of words. The section shown here is from the introduction, describing Alexander the Great (the “two-horned one”) and a King of India:

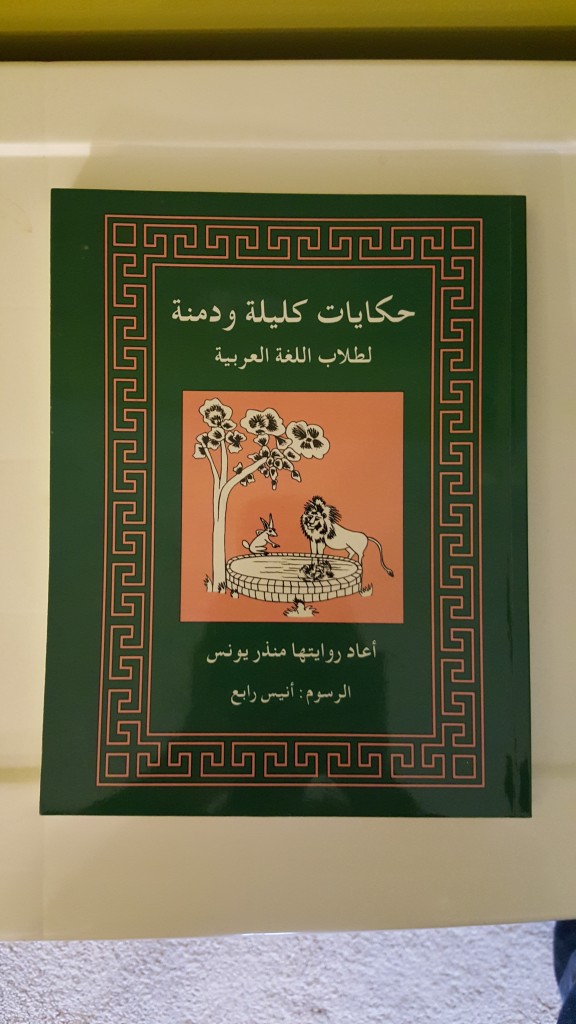

Most readers, even in the Arabic-speaking world, are unlikely to tackle the original unabridged edition, as I was bold enough to attempt. For them are edited versions, using more modern and colloquial terms.

Here is one such edited, abridged version, which I also own:

Ibn Muqaffa changed some of the features of the original Indian text. He places the era of the work during the time of Alexander the Great’s (called “he with two horns” or ذو القرنين) invasion of India, and includes an extended prooemium, or introduction. The general premise is that an Indian wise man (named Bidpai) has been commissioned to collect a book of wisdom. He does this, and the book is secreted away for safe keeping. A Persian king later hears of this precious book of wisdom, and desires a copy for himself. This is accomplished through a long and arduous process.

The names “Kalila” and “Dimna” are the names of two jackals that feature in the book. In the beginning of the book, Dimna has been accused of causing the death of a noble bull named Shanzabeh. Other animals testify against Dimna, he is convicted, and promptly executed. The message is thereby sent that human relations is a serious business, and anyone wishing to improve his knowledge of the same must study it with the gravity it merits. Anyone who enjoys books of wisdom, practical life advice, and world literature will profit from exposure to this work.

Readers are encouraged to explore the riches of this book in one of the best modern English translations, available here.

Its advice is timeless, and its lessons never fail to resonate.

Read More: The 5 Essential Elements Of Creativity

You must be logged in to post a comment.