A news agency recently reported the discovery of the tomb of Suleiman the Magnificient, who by general consensus was the greatest of all the Ottoman sultans. Suleiman, who lived from 1494 to 1566, is now nearly unknown in the West; but he was, in the words of one eminent historian, “the greatest and ablest ruler of his age.”

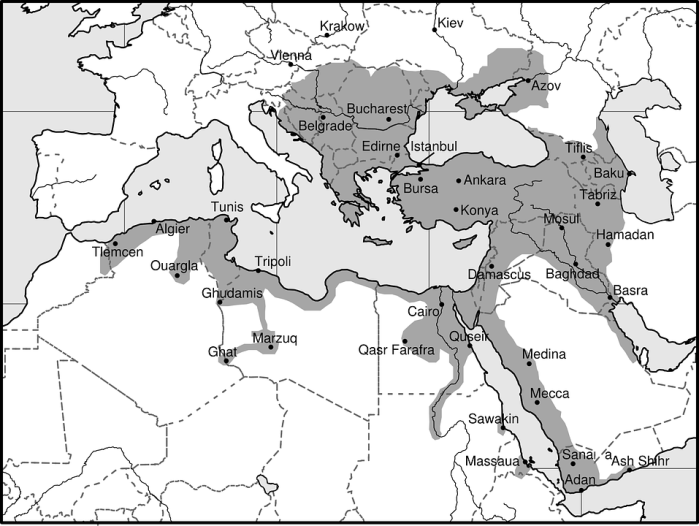

In the Muslim world, Suleiman is known as “Qanuni” or “the Lawgiver,” for his efforts at reforming the complex Turkish legal code. The name “Magnificent” was actually affixed on him by Western admirers who eyed possessively the extent of the vast Ottoman domains, which in his day stretched from Algiers to Baghdad. He also took pains to adorn his cities in splendor; the famous “Forty Arches” aqueduct was completed at his bidding, as well as countless public buildings, mosques, and public squares. His rule also oversaw a flowering of cultural and artistic achievements.

He was–embarrassingly for European states–more tolerant of foreign religions than his Christian counterparts. He did not molest Christians or Jews, and promised the unfettered practice of all faiths in his domain. A Catholic Cardinal would write, “The Turks do not compel others to adopt their beliefs. He who does not attack their religion may profess among them what religion he will; he is safe.” There is ample evidence that some Christian communities actually preferred to be under Ottoman rule, as the Turks, bewildered by the proliferation of Christian sects, were more even-handed than Christian princes. We may contrast this picture with what was going on in Western Europe at the same time, where Protestants and Catholics were slaughtering each other with dedicated enthusiasm.

This picture is not quite perfect, of course, for Suleiman had the vices of all leaders trying to keep together a vast and unwieldy collection of peoples. Corruption and lassitude certainly thrived in Turkish lands, and we miss that commercial vitality that characterized the freewheeling merchant spirit of Holland or Venice in the same period. While Suleiman did not abandon himself to the sexual corruption of the harem to the extent that some later sultans did, he did devote his attentions to elevating his favorite concubine (Roxelana, or “The Laughing One,” also known as Khurrem) to the palace. And he was as addicted to war as any prince of his era.

When he died at the age of 72, he was personally leading an army of over 200,000 men to punish Maximilian II, who had held back the tribute his father promised the Turks. Maximilian also had the temerity to attack Ottoman outposts in Hungary. The Turks actually won the battle of Szigetvar, but the loss of over 30,000 men in the campaign made its continuance inadvisable. Suleiman’s army–and his corpse–reversed course and rode quietly back to Constantinople. He was dead, but in 1568 Maximilian resumed payment to the sultans; and the Turkish navy still controlled the Mediterranean. One might argue that Suleiman had accomplished his objective.

Suleiman died in 1566 while his army was engaged in military operations near Vienna. Part of his remains were buried in what is now Hungary; but when the Hapsburg rulers retook the area in the 1680s, Suleiman’s mausoleum was razed, and its location eventually became lost. It is a familiar story in history, and has been repeated over and over. After many years of searching for the actual grave site, a joint Hungarian-Turkish team seems finally to have found the location of the old mausoleum. As one participant in the dig stated:

“The findings of the surveys done before the excavations were so clear that it was like cleaning sands over a partially visible subterranean wreck … We were all joyful for sure,” said Ali Uzay Peker, a professor of architectural history at Ankara’s Middle East Technical University.

“Last year, the foundation of a square building was unearthed and identified as the tomb of Suleiman. This year, the mosque and tekke [a Dervish cloister] were excavated,” he explained.

“Tools of [16th-century] daily use like coins, knives, potsherds, pipes; architectural fragments … and the layout of the buildings in relation to each other support written and pictorial documentation and technological analyses. So we can say that we unearthed Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s tomb.”

A commemoration will be held at the location (Szigetvar) on September 7. Dignitaries from Turkey, Croatia, and Hungary will be present (the Turkish advance at Szigetvar was halted by Hungarian and Croatian forces). Local authorities are hoping that the discovery of the tomb will bring in much-needed tourism and capital to the area. Researchers have even found descendants of Ottoman royal family to make DNA test comparisons in case any organic material is found at the gravesite.

The great men of European history continue to exert a hold on the minds of their descendants. Their ghosts still haunt the quiet and forgotten fields of the old continent. And Europe’s complex and turbulent relationship with the Islamic world–characterized by admiration and disdain in equal measure–seems to get more intriguing every year. The relics of history are everywhere around us; and there is nothing that ages so well as departed glory. The story is not just in the stones of fallen buildings or temples: it is everywhere. We need only to listen, for a story can be heard everywhere. As the Arabic saying goes:

لكل مقام مقال

And this means, “A discourse is for every place.”

Read Pantheon today to experience the power of historical exemplars, ethical philosophy, and the mind:

You must be logged in to post a comment.