In our lives we often encounter people whose behavior seems to make no rational sense. I am referring to people who do things that seem to be against their own self-interest: those who say one thing, but do something else. We ourselves can fall into this trap on occasion. It is almost as if there exists some morbid consciousness in all of us, a voice calling out for us to exactly what we should not do.

Different ages and eras have interpreted this negative aspect of the soul in various allegorical ways. For me it is enough to acknowledge its existence, its omnipresence, and its destructive power. There is a certain turbulence in the soul which can manifest itself in varying degrees of tumescence; at times it is a moderately placid sea, and at other times it is all white-capped, billowing waves, battering the hull of our ship. Petrarch wrote a letter in 1354 to Giovanni Aghinolfi (Giovanni of Arezzo) in which he stated:

We suffer from the bad acts we have done, and adverse consequences often fall back on the head of him who commits such acts. We are not kept down by others, nor is it right that we should be…

[Patimur mala quae fecimus, et saepe in caput auctoris poena revertitur. Non aliunde premimur, nec oportet…]

Petrarch then goes on to quote the title of a work by John Chrysostom that reinforces this point: No One Can Be Harmed Except by Himself (Nisi A Semet Ipso Neminem Laedi Posse). Now of course we all know that this is true only to a certain extent: outside oppression can exist, and one can very much be harmed by others. But if we think about this, and carefully examine our own life and the lives of others who are experiencing problems, we can easily see that Petrarch’s point is true more often than it is not true. We are the creators and authors of most of our problems, and it is for us to remedy such problems. To take a different position as a matter of faith is to surrender control of one’s free will—insofar as it exists outside of Fortune—and amounts to abandoning the responsibilities of life.

I was watching a documentary the other day about the construction of a massive sarcophagus to house the radioactive remains of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor. When the reactor exploded in 1986, its destructive debris was spread over a wide area. The reactor itself was entombed in a hastily assembled edifice that almost immediately began to fall apart. The site constantly emits gamma rays and other radiation, and the only way to prevent a recurrence of the problem is to enclose it once again in an immense, permanent dome. This “shell,” if we may call it that, will contain and suppress all the waves of poison emanating from the ruined and exposed reactor core.

I mention this in order to make the following analogy. We can see the distressed soul as akin to this ruined reactor: it is constantly emitting harmful radiation, and can contaminate others who spend too much time within its range. It is this toxic nature that causes such people to do things that are obviously against their better interests. Now, you may say, “The reason why so-and-so does things against his own interests is because he has a drug addiction problem. It is a chemical matter, and not a moral or ethical matter.” And my answer to this would be: “Yes, this may be true as far as that goes, but what made him become a drug addict in the first place? What agony of soul, what inner turbulence and instability, caused him to seek relief in drugs in the first place?” It is clear that if we go to the root of most personal problems, we can find some lack of alignment in the soul’s constitution, which in turn manifests itself as a moral or character problem.

I think this is why St. Augustine said the following words in his Confessions (VIII.9):

Therefore there is no grotesque division between “wanting” and “not wanting,” but rather a sickness of the mind. When it is voluntarily raised up, it does not rise up completely, but is dragged down by one’s habits. Thus there are two wills, since one of them does not control everything, and what is present in one is absent in the other.

[Non igitur monstrum partim velle partim nolle, sed aegritudo animi est, quia non totus assurgit, voluntate sublevatur, consuetudine pregravatur, et ideo sunt duae voluntates, quia una earum tota non est, et hoc adest alteri quod deest alteri.]

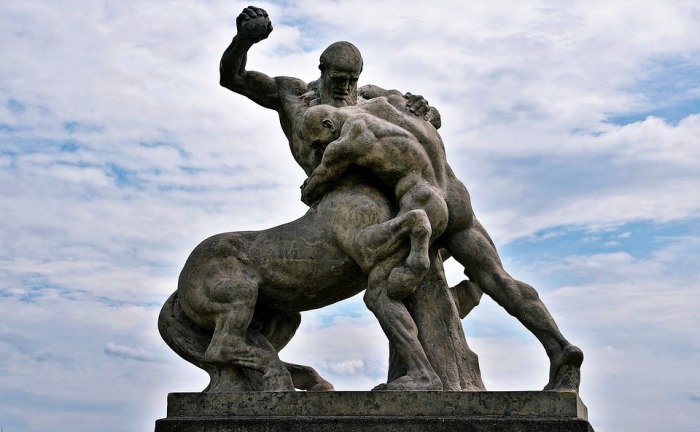

So we have a sickness of the mind at work. The better instincts do not “rise up” completely, because they are dragged down by the negative forces of habit. This explains why we often do things that are against our own interest. There is not just one tugging influence on the soul: there are, in fact, two forces competing for the soul’s direction. We have the will, and we have the force of habit. Habit is like inertia: it carries a certain momentum of its own, and wants to resist any kind of positive change. So how can we learn to restrain this rebellious soul, this soul that spews out harmful rays like the melted core of the Chernobyl reactor? The answer is that it must be tamed by individual force of will: the will must, like the shell entombing that reactor just mentioned, demonstrate its dominance over it. It must smother the soul’s destructive, negative aspects. And this grappling, this wrestling, can take years of effort. I have used the language of conflict in describing it, because conflict is exactly what it is.

In Virgil’s Georgics (IV.387 et seq.), the poet provides a most relevant image along these lines. Cyrene tells Aristaeus that “in the Carpathian gulf of Neptune” there exists a soothsayer named Proteus, who goes about in a chariot drawn by fish and horses. Cyrene tells him that he must seize this Proteus, put him in chains, and make him reveal his secrets:

For without force, he will not give up his secrets; and you will not sway him with prayers.

Use decisive force and clap him in chains,

His hollow tricks will eventually be broken around these.

Persuasion and mind games only work so far. You cannot subdue a radioactive force with benedictions and prayers. You must house it, contain it, entomb it, and enshrine it under a sarcophagus. This is the method that must be used in taming and subduing the wayward soul. It will resist attempts to control it, of course. There is that competing force of “habit” that Augustine mentioned in the previous quote, and this force pulls the soul in the opposite direction. Some will be successful in mastering themselves; some will be moderately successful, and some will not be successful at all, and will remain a slave to their own baser natures. A man does not change until he wants to change: until he wants to clap his Proteus in chains, and force this imp to submit. Some have the strength to accomplish this; and some do not even wish to try. In the end, each person must decide for himself, and live with the consequences.

Read more in On Moral Ends:

You must be logged in to post a comment.