The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word elasticity in the following way: “Of material substances, whether solid, liquid, or gaseous: that spontaneously resumes (after a longer or shorter interval) its normal bulk or shape after having been contracted, dilated, or distorted by external force.”

The first recorded use of the word in the sense defined dates to 1674. It was the British scientist, experimenter, and architect Robert Hooke who first described the law of mechanics governing the principle of elasticity. In its simplest definition, Hooke’s Law states that materials stretch in direct proportion to the force applied to them.

Like many historical discoveries and innovations, it seems today almost obvious in retrospect. One could say the same thing about the invention of the telescope or the microscope: after all, are not these inventions only lenses placed inside hollow tubes, through which the gaze of a curious eye may be directed? It is indeed tempting to congratulate ourselves on our high level of advancement. But we may be assured that future generations will look back at our own era and wonder why we could not see what was so obviously in front of our eyes. For perception requires not just sight, but a mind bold enough to accept novel ways of thinking.

Robert Hooke was born on the Isle of Wight in 1635. He showed an early aptitude for mechanical observation and experimentation, but poverty and a lack of connections slowed his progress. He moved to London in 1648 on the death of his father; by the late 1650s he was active as an experimenter and assistant to prominent scientists of his day, such as Thomas Willis and the chemist Robert Boyle. Hooke’s aptitude for mathematics, curiosity, and ability to design experiments placed him in the first rank of European scientists. In 1660 he discovered what became known as Hooke’s Law. He articulated it elegantly in Latin: Ut tensio, sic vis (“Just as the stretching, so the force”). Hooke’s Law remains a standard consideration in construction problems, engineering, and architecture.

Recognition eventually came. In 1662 he was appointed curator of experiments for the Royal Society. In 1665 Hooke published the landmark work Micrographia, which catalogued his studies of plants and insects with microscopes. Even astronomy beckoned him; he discovered the fifth star of Orion, made tentative steps toward a theory of gravitation. He was not the first to suggest the use of springs in watch construction, but saw their potential, and later generations would build on his foundation.

All in all, Hooke had an astonishing record of achievement in mechanics, physics, astronomy, biology, and even geology (for he argued that fossils in successive ground strata proved the extreme age of terrestrial life). Will Durant’s assessment of his career is not an exaggeration: “He was probably the most original mind in all that galaxy of geniuses that for a time made the Royal Society the pacemaker of European science; but his somber and nervous nature kept him from the acclaim he deserved.”

It is fascinating to see the application of physical laws in the resolution of practical problems. Hooke’s Law presents us with a brilliant example: its employment in the science, or art, of navigation. We take for granted today the ability of ships to travel freely over the world’s oceans. But it was not always so. If they are to fix their location and avoid wreckage and death, mariners need to be able to plot courses over long distances. They need to know their location at all times. In ancient times, this was a problem that could be dealt with by hugging the familiar coast of the Mediterranean or other friendly places; but as man ventured over the globe, he needed to chart extended courses and avoid perils. Dead reckoning and the seaman’s instinct have only so much utility. For centuries the problem of measuring latitude (the distance north or south of the equator) had been substantially solved by monitoring the angles of the sun or certain stars from the horizon. But longitude (the angular distance of a place east or west of a fixed meridian) was an entirely different matter.

Longitude can be measured by comparing one’s present time at sea with the time of some known place on land, such as Greenwich in London. For us in 2023, this is very easy to do. All that is required is to consult a reliable digital timepiece. But until the 18th century, measuring longitude precisely was nearly impossible. Clock technology simply had not advanced sufficiently to permit accurate time measurements to be made at sea. The most accurate clocks at the beginning of the 18th century used pendulums, and these were nearly useless aboard ships. Pendulums rolled about with the waves, were cumbersome and bulky, and their greasy lubricants expanded and contracted as torrid and frigid zones were alternately experienced.

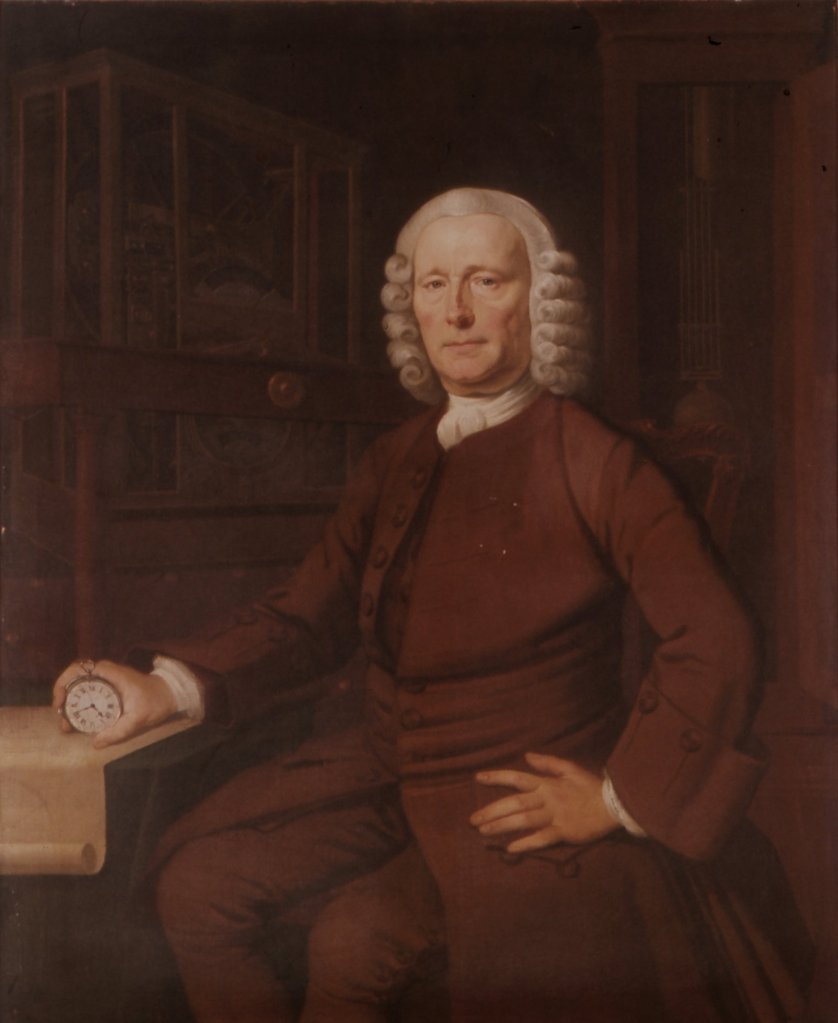

What was needed was an entirely new way of approaching the problem. Ship captains needed reliable, precise timepiece that could be carried aboard ship, and that would function in both freezing and tropical temperatures. The problem was so acute that, in 1714, the British Parliament passed the so-called Longitude Act: it offered a colossal reward of 20,000 pounds to anyone who could develop a reliable way of calculating longitude. The challenge was taken up a solitary mechanical genius named John Harrison, who, after many years of labor, invented new timepieces (“chronometers”) that were truly ship-worthy. These brilliantly designed chronometers, of which there are four, have been assigned the names H-1, H-2, H-3, and H-4. Harrison’s inventions incorporated a variety of innovations, but perhaps the most crucial was his use of Hooke’s Law in the design of his machines’ internal springs.

Metallic springs expand and contract considerably with temperature. Harrison’s H-3 chronometer took advantage of Hooke’s Law by employing bi-metallic strips in its spring design. Different metals, such as brass and steel, expand and contract at different rates. After much experimentation, Harrison confirmed that fine springs made with brass and steel riveted together could automatically compensate for temperature changes, and maintain the chronometer’s accuracy. The same principle is used today, we are told, in the design of thermostats and other temperature-sensitive devices. It was a brilliant solution to an ancient problem, and an edifying illustration of the practical application of theoretical physical laws.

.

.

.

Read more about great discoveries and innovations in Thirty Seven:

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.