The new, annotated translation of Cicero’s classic On the Nature of the Gods (De Natura Deorum) is now available in paperback, hardcover (with classic dust-jacket), and Kindle editions. An audiobook edition will follow in October.

Work on On the Nature of the Gods commenced immediately after the publication of the translation of Tusculan Disputations in 2021. It is the product of two years of continuous and gratifying labor. It is the first original translation of this classic to appear in many years, and I believe it is ideal for the student or general reader. The paragraphs below will explain what the book is about, why it is important, and what features this translation offers the modern reader or student.

On the Nature of the Gods is a work of philosophy composed in dialogue form. Do the gods exist? If so, what is their nature? Is there a divine order to the universe? And if there is, what is humanity’s role in this grand conception? Does a divine power care about human affairs? These are just a few of the profound questions discussed in Cicero’s philosophical masterpiece.

In dialogues that showcase the differing perspectives of the Stoic, Epicurean, and Academic schools, Cicero delves into a prodigious variety of subjects, including human anatomy, theology, cosmology, astronomy, biology, and divination. The persistent themes of Cicero’s vision are his insistence on a moral basis for human conduct, the existence of free will, and his soaring faith in the unique role reserved for the human race in the universe’s destiny. It is no wonder that Voltaire called On the Nature of the Gods, along with Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, “[the] two most beautiful works ever composed by human wisdom.”

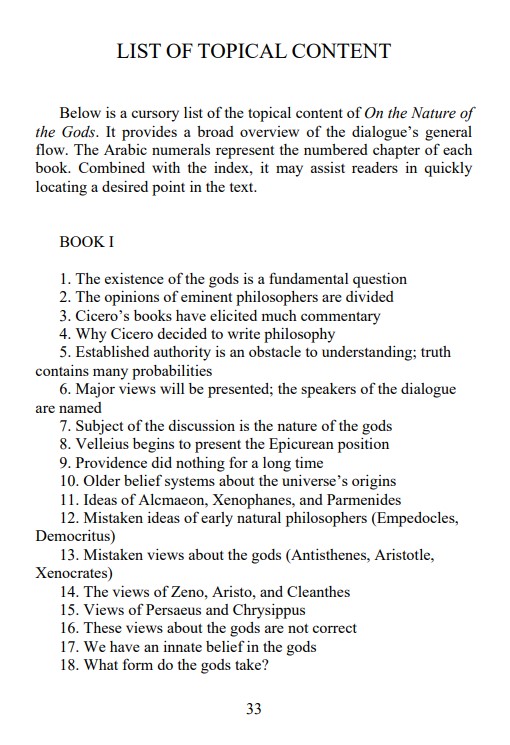

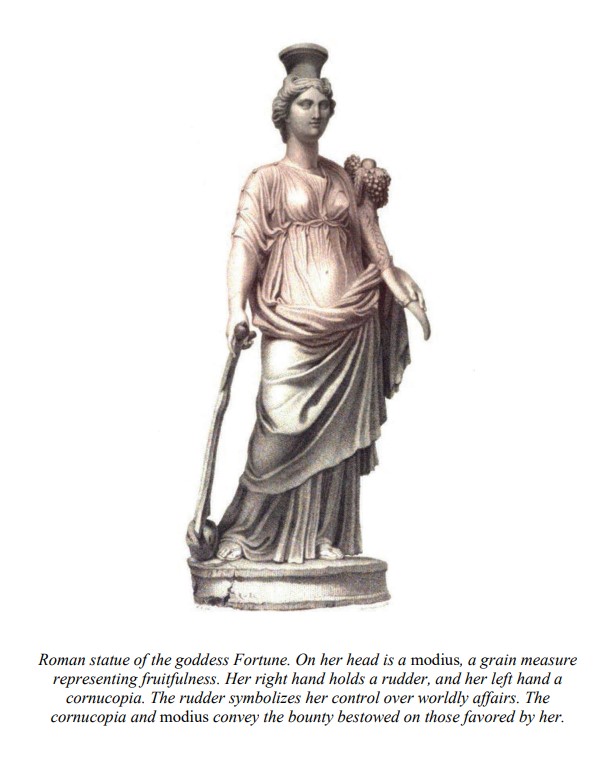

This is the first complete, original translation of On the Nature of the Gods to appear in many years. My goal has been to produce a fresh, modern English edition that breathes new life into a long-neglected classic of Western thought. The text is extensively annotated, and formatted using modern dialogue conventions for ease of reading. It includes a foreword, a detailed introduction, a useful list of topical contents, illustrations, and a comprehensive index. Cicero’s seminal work has much to tell us today, and with this translation has never been more accessible to the modern reader. Below is an excerpt from the Foreword:

Few subjects in philosophy have so consistently engaged the interests of contemplative minds through the centuries as the question of a divine power. Does a supreme being exist? What unseen forces govern the universe? If a divine power does exist, what is its nature? What is the nature of our relationship to it? Does a divine power care about the affairs of mankind, or does it ignore us completely? And as a practical matter, how should we go about investigating this recondite and elusive subject?

What impresses the modern student of philosophy is the fearless readiness of ancient thinkers to propound comprehensive answers to these questions. Despite the wide divergence of perspective among the classic philosophical schools, each of them offered systematic views on the nature and operation of the universe. The ancient schools were not always able to reconcile their cosmologies with the accepted religious beliefs of their day; and, acutely aware of the fates of Socrates and other philosophers who strayed beyond the acceptable limits of impiety and apostasy, they often confined their opinions to sympathetic adherents, or adopted a protective coloration of didactic ambiguity. But in these brave early efforts we feel the first stirrings of mankind’s struggle to understand his place in the cosmos. It is a struggle that has continued to the present day.

Cicero’s On the Nature of the Gods (De Natura Deorum) is the fullest comparative study of ancient theology that has come down to us. Most of the sources that Cicero mentions in his treatise—and as the reader will see, there are many of them—have not survived the ravages of time. The works of Epicurus, Zeno, Cleanthes, Posidonius, Xenophanes, Anaxagoras, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Democritus, and Clitomachus, to name only a few, are known to us only as tantalizing fragments, if at all. Yet Cicero’s work has survived. This fact alone assures the work a prominent place in the history of philosophy.

But as we will discuss in the Introduction, On the Nature of the Gods is a crucial document not simply because it preserved the ideas of some Greek philosophers who predated Cicero. It is an original and profound work in its own right, and is fit to stand alongside the great classics of Western philosophical thought. It offers penetrating analyses of religion’s role in human affairs, man’s place in the cosmos, divine providence, the problem of evil, the necessity of human agency, and the need for free will. The tone throughout is rationalist; but it is a rationalism buttressed by a powerful and inspiring sense of moral purpose. It was not without reason that Voltaire, in his Philosophical Dictionary, identified On the Nature of the Gods, together with Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, as “the two noblest works that were ever written by mere human wisdom.”

On the Nature of the Gods is a dialogue between three speakers, each one representing a particular philosophical viewpoint. The three books of the treatise comprise four general subjects: (1) a review of the opinions of some important early philosophers, and the basic ideas of the Epicurean and Stoic systems; (2) an explanation of the Epicurean position on the nature of the gods; (3) an explanation of the Stoic position on the subject; and (4) a general critique of both the Epicurean and Stoic positions from the perspective of Academic skepticism. Cicero is present during the dialogue, but does not participate actively in it. From references in the text, scholars have dated the composition of the work to 45 B.C.

In the modern era, On the Nature of the Gods has been relatively neglected by both professional scholars and students of philosophy. The general decline in classical learning has something to do with this, but I suspect there are other reasons as well. Discussions about religion and the divine nature unavoidably agitate our most deeply held convictions. Views that do not align with our own are unlikely to receive a warm reception. Even in antiquity, Cicero’s foray into these abstruse questions aroused the ire of both the pagan philosophical schools and some early Christian thinkers. The Epicureans and Stoics resented Cicero’s withering attacks on their philosophies, while some Christian apologists were angered both by his rational ambivalence on the divine nature, and by what they viewed as a utilitarian attitude toward religion that relegated faith to almost an afterthought. These points will be explored in more detail in the Introduction.

But with the advent of the Age of Reason, and later the Enlightenment, rationalist and skeptical approaches to the divine nature became more accepted, at least among the educated. Descartes thought he could prove the existence of god with ontological reasoning, thereby implicitly acknowledging the supremacy of reason; Montaigne’s polite essays elevated skepticism to a literary art form; and Leibniz privately adhered to Spinozism, while outwardly affirming the accepted theology of his day. In England and colonial America, deism flourished as a philosophical movement.

Deism thoroughly rejected the supernaturalist and revelationist doctrines of the conventional theologians, and held that ethical conduct should be based on conscience, virtue, and social responsibility. Deists accepted the existence of a rational and benevolent deity, and argued that this Divine Architect revealed itself through nature’s laws. Thus the rational study of nature was, in their view, an essential path towards understanding the divine nature. While it would be going much too far to call Cicero a proto-deist, it is still interesting to point out similarities between his arguments in On the Nature of the Gods and some ideas articulated by Enlightenment-era thinkers many centuries later.

A new and annotated translation of On the Nature of the Gods has been needed for many years. The text demands readable modern diction, conventional formatting, and a sentence structure free of Victorian archaisms and interminable clauses held together by rickety semicolons. At the same time, there must be a scrupulous fidelity to the words and tone of the original work. This is the approach I have used in translations of other Ciceronian treatises. It is hoped that this present effort will help revive interest in an undeservedly overlooked classic of Western thought.

Below are provided views of some pages of the text:

__

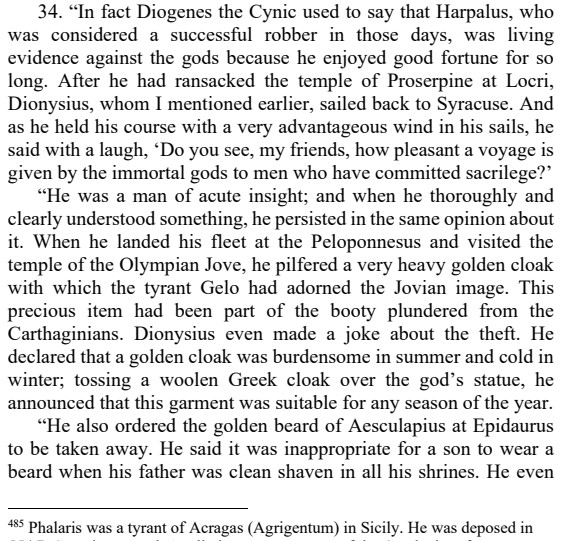

The following are some other excerpts from the book. The truth is, says Cicero, that evil not only exists, but often triumphs or goes unpunished. He provides some examples, in a passage from III.34:

__

Below is a passage from III.27. There are many fools in the world, and perhaps the divine will cares only about those whom it gave “principled reason.” In fact it may be that the gods care nothing about us at all:

__

We may attribute material wealth to divine favor. But no one, says Cicero, ever attributed earned virtue to a god. We know that virtue has to be earned, and not gifted (III.36):

This new translation of Cicero’s On the Nature of the Gods is available at all major booksellers. If you have any questions or comments, please contact me at qcurtius@gmail.com.

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.