The curious mind may be puzzled by the apparent paucity of commercial and cultural contacts between the Roman and Chinese empires. That these two mighty states seem to have had such meager intercourse with each other, for so many centuries, is one of the oddities of antique history.

Yet they did maintain some mutually beneficial interactions, albeit restricted in scope. Before we describe these contacts, we must first recall the vast distances and difficulties of travel that tested the intrepidity of ancient merchants. Simply to reach China from Rome’s eastern territories was an expensive and perilous undertaking. Gibbon tells us (Ch. XL) that, while the cities of Samarkand and Bokhara were ideally situated for overland trade, silk caravans trekking from Samarkand to China’s western edge could make the journey in no less than “sixty, eighty, or one hundred days.” The route was a dangerous one; robbers and bandits considered caravans fair game, and employed all their cunning and ruthlessness to siphon treasure from foreign prey.

The situation was somewhat better by sea. Chinese silk merchants, sailing from Sumatra and accompanied by stores of aloes, cloves, nutmeg, and sandalwood, conducted trade at Ceylon with the inhabitants of the Persian Gulf. Yet for the Romans and Greeks, the remote nations of the East had always been cloaked in obscurity. Strabo, Pliny, Ptolemy, and Arrian contented themselves with legends, speculations, and rumors, a sentiment that was reciprocated on the Chinese side. But it does seem strange that Chinese technological advances, such as the crossbow and printing, never percolated to the Mediterranean region. The knowledge of silk manufacture did eventually find its way to Greece, but this was accomplished only by the subtle daring of monks willing to hazard their lives to conceal silkworms within the hollows of walking staffs. “I am not insensible to the benefits of elegant luxury,” intones Gibbon, “yet I reflect with some pain that, if the importers of silk had introduced the art of printing, already practiced by the Chinese, the comedies of Menander and the entire decads of Livy would have been perpetuated in the editions of the sixth century.” We share his regret.

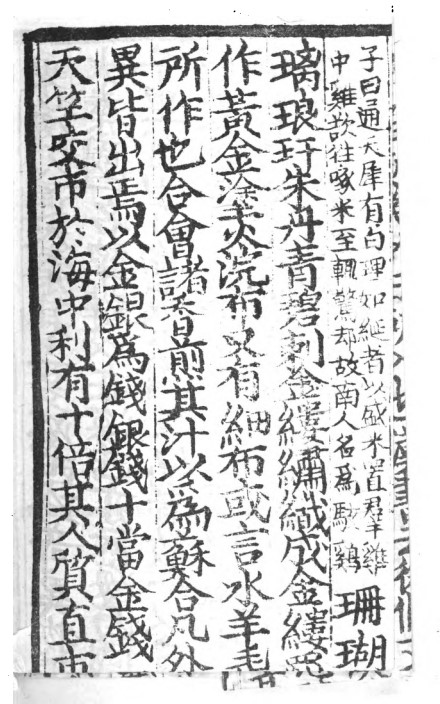

The two great empires were, however, aware of each other. F. Hirth’s China and the Roman Orient: Researches into Their Ancient and Medieval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records, published in 1885, is still a fascinating exploration of the subject. According to Hirth, who pored over and translated the original Chinese texts, the earliest reference to the Roman empire in Chinese documents is in a historical chronicle called the Hou-han-shu, which was composed in the fifth century A.D. The Hou-han-shu, first printed during the Sung Dynasty, was a compendium of original notes and commentaria made by court chroniclers, and covered the period from A.D. 25 to 220. Its objectivity and veracity are enhanced by the fact that it was concealed from the biased scrutiny of the Chinese emperor himself.

According to the Hou-han-shu, in 97 A.D. an emissary from the Chinese court named Kan-ying was sent to a distant region or city called “Ta-ts’in.” Kan-ying reached a city named T’iao-chih, located on the coast of a large sea. But here, Kan-ying was advised not to undertake a sea voyage. The relevant Chinese text reads as follows, as rendered by Hirth:

When about to take his passage across the sea, the sailors of the western frontier of An-hsi [Parthia] told Kan-ying: “The sea is vast and great; with favorable winds it is possible to cross within three months; but if you meet slow winds, it may also take you two years. It is for this reason that those who go to sea take on board a supply of three years’ provisions. There is something in the sea which is apt to make man home-sick, and several have thus lost their lives.” When Kan-ying heard this, he stopped. [Hirth, p. 39]

According to Hirth, “Ta-ts’in” was a flexible Chinese term used to denote the eastern Roman empire, particularly Syria or Antioch. Matters are made somewhat more confusing by the fact that the name Ta-ts’in came to be replaced by the term Fu-lin during the medieval period. Using the clues found in Chinese records, Hirth is able to show convincingly that Chinese trade routes in late antiquity went through Parthia, then around the Arabian peninsula to the Red Sea to the city of Petra.

Parthian merchants, therefore, were the commercial middlemen between the eastern Roman empire and China. They jealously guarded this position. According to the Hou-han-shu, “The kings of Ta-ts’in always desired to send embassies to China, but the An-hsi [Parthians] wished to carry on trade with them in Chinese silks, and it is for this reason that they were cut off from [direct] communication.” So ancient is the lust for monopoly. However, things would change with the campaigns of Marcus Aurelius against the Parthians in A.D. 166. His exertions opened the door to direct contacts between Rome and China. The Hou-han-shu reveals:

This [situation where the Parthians blocked direct contact] lasted till the ninth year of the Yen-hsi period during the emperor Huan-ti’s reign [i.e., A.D. 166 ] when the king of Ta-ts’in, An-tun, sent an embassy who, from the frontier of Jih-nan [Annam] offered ivory, rhinoceros horns, and tortoise shell. From that time dates the [direct] intercourse with this country…One is not alarmed by robbers, but the road becomes unsafe by fierce tigers and lions who will attack passengers, and unless these be travelling in caravans of a hundred men or more, or be protected by military equipment, they may be devoured by those beasts. They also say there is a flying bridge of several hundred li, by which one may cross to the countries north of the sea. [Hirth, p. 42]

The “flying bridge” described above is suggested to be the bridge spanning the Euphrates at Zeugma. Hirth identifies “the king of Ta-ts’in, An-tun” as Marcus Aurelius, with “An-tun” being a Chinese corruption of the name Marcus Antoninus. We have no record, however, of a formal delegation sent by Marcus Aurelius to the court of the Chinese sovereign. What seems more likely is that Syrian merchants financed and conducted commercial expeditions on their own while making use of the emperor’s name. Silks came to the Mediterranean region from China, while Rome provided to the Chinese precious stones, glassware, Syrian and Phoenician textiles, and a natural resin called storax. It is also clear that Ceylon was a location where eastern Roman and Chinese commercial vessels met and exchanged goods.

What is remarkable about all this is that Roman contacts with China never escalated to the level of cultural borrowings that we see in Greek and Roman intercourse with Persia or India. China was simply too far away, too secretive, and too closed to foreigners. The impression formed from an examination of the original sources is that Rome and China received the articles and raw materials they wanted from each other, but felt no inclination to elevate their tenuous contacts to a higher level.

.

.

Take a look at the new annotated and illustrated translation of Cicero’s On The Nature Of The Gods.

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.