Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Sphinx is not one that readers may be immediately familiar with. Despite having been composed in 1850, its lesson resonates powerfully in the age of social media and unrelenting news cycles.

The narrator of the tale begins by informing us that New York’s cholera epidemic has forced him to “spend a fortnight” at the home of a friend on the banks of the Hudson River. (There was, in fact, a serious outbreak of cholera in New York in 1832). News of the climbing fatalities from the disease has darkened our narrator’s spirit; he is weighed down by a pervasive sense of doom and powerlessness. “At length,” he says, “we trembled at the approach of every messenger.” Things are not helped by the fact that the narrator has fixated on reading dreary tomes in his friend’s library that augment, rather than alleviate, his crushing melancholia.

Inevitably the narrator’s mind turns to the subject of omens. He is inclined to believe that they may contain the seeds of truth, while his friend, whose mental equilibrium seems unaffected by the unfolding cholera tragedy, argues for their utter groundlessness. One day, as the narrator is reading, he pauses to look out the window. To his horror, he sees a terrible and gigantic monster crawling across the hills of the distant landscape:

As this creature first came in sight, I doubted my own sanity—or at least the evidence of my own eyes; and many minutes passed before I succeeded in convincing myself that I was neither mad nor in a dream…Estimating the size of the creature by comparison with the diameter of the large trees near which it passed—the few giants of the forest which had escaped the fury of the land-slide—I concluded it to be larger than any ship of the line in existence.

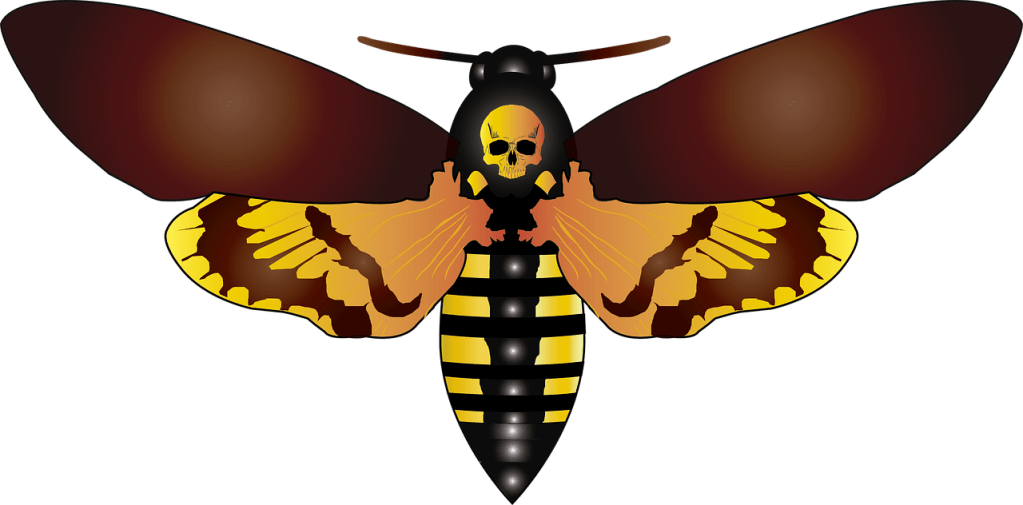

The monster appeared to have a proboscis sixty or seventy feet in length, at the end of which was situated a loathsome mouth. It had scaly wings, and was covered with black, shaggy hair. What particularly shocked the narrator was the image of an apparent death’s head imprinted on the creature’s breast: “While I regarded this terrific animal, and more especially the appearance on its breast, with a feeling of horror and awe—with a sentiment of forthcoming evil, which I found in impossible to quell by any effort of reason, I perceived the huge jaws at the extremity of the proboscis, suddenly expand themselves, and from them there proceeded a sound so loud and so expressive of woe, that it struck upon my nerves like a knell, and as the monster disappeared at the foot of the hill, I fell at once, fainting, to the floor.”

This strange sighting deeply unsettles the narrator. He is unsure if he is losing his grip on sanity, and hesitates to disclose the experience to his friend. Finally he does reveal, in exact detail, what he saw; and he is relieved to find the friend a rational and unperturbed confidant. After hearing the narrator out, the friend reminds him that the “principal source of error in all human investigations [is found] in the liability of the understanding to under-rate or to over-value the importance of an object, through mere misadmeasurement of its propinquity.” In other words, our perception of reality may easily be distorted, or confounded, by an overreliance or underreliance on any number of factors. Perspective, it turns out, is everything.

To illustrate what he means, the friend walks over to his bookshelf and takes down a volume on natural history. He eventually finds what he is looking for, and shows it to the narrator. It is an entry related to an insect “of the genus Sphinx, of the family Crepuscularia, of the order Lepidoptera.” The insect is described as having an elongated proboscis, mandibles, and metallic-looking scales. The entry further states that “[t]he Death’s-headed Sphinx has occasioned much terror among the vulgar, at times, by the melancholy kind of cry which it utters, and the insignia of death which it wears upon its corslet.”

The friend then makes a further demonstration. He sets down the book and seats himself in the very chair the narrator used when first sighting the distant monster. After some peering and shifting his position, he finally sees what he is looking for: the Sphinx insect itself—only about one-sixteenth of an inch in length—crawling along a filament of spider-silk only a fraction of an inch from the pupil of his eye. This, then, was the “monster” that had so terrified the narrator the day before.

The first lesson of philosophy, said Will Durant, is perspective. Has any story so ably illustrated this maxim than Poe’s brilliant three-page tale? If one has, I am not aware of it. How many erroneous opinions, how many flawed conclusions, how many punji-pits of incomprehension, have otherwise intelligent men committed themselves to, by failing to remain mindful of perspective!

That which dominates our thoughts, we tend to see in the outer world. Our fears, our hopes, our secret musings: all of these things skew the processing of what our sense-receptors tell us. He who imagines the attainment of certitude in isolation only deludes himself. Ideas, propositions, and proposals must be bounced off others; they must be discussed, tested, and subjected to the crucible of rational analysis. The distorting effects of subjective observation are nowhere more apparent than on social media and news channels, where cherry-picked video clips, quotes, and other information morsels can send us down twisted rabbit holes of nescience. In the media age, Clausewitz’s “fog of war” (Nebel des Krieges) must be accepted as a permanent condition.

.

.

.

Take a look at the new, annotated translation of Cicero’s On The Nature Of The Gods:

.

A nice word, perhaps even polite, “nescience”. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Allen!

LikeLike