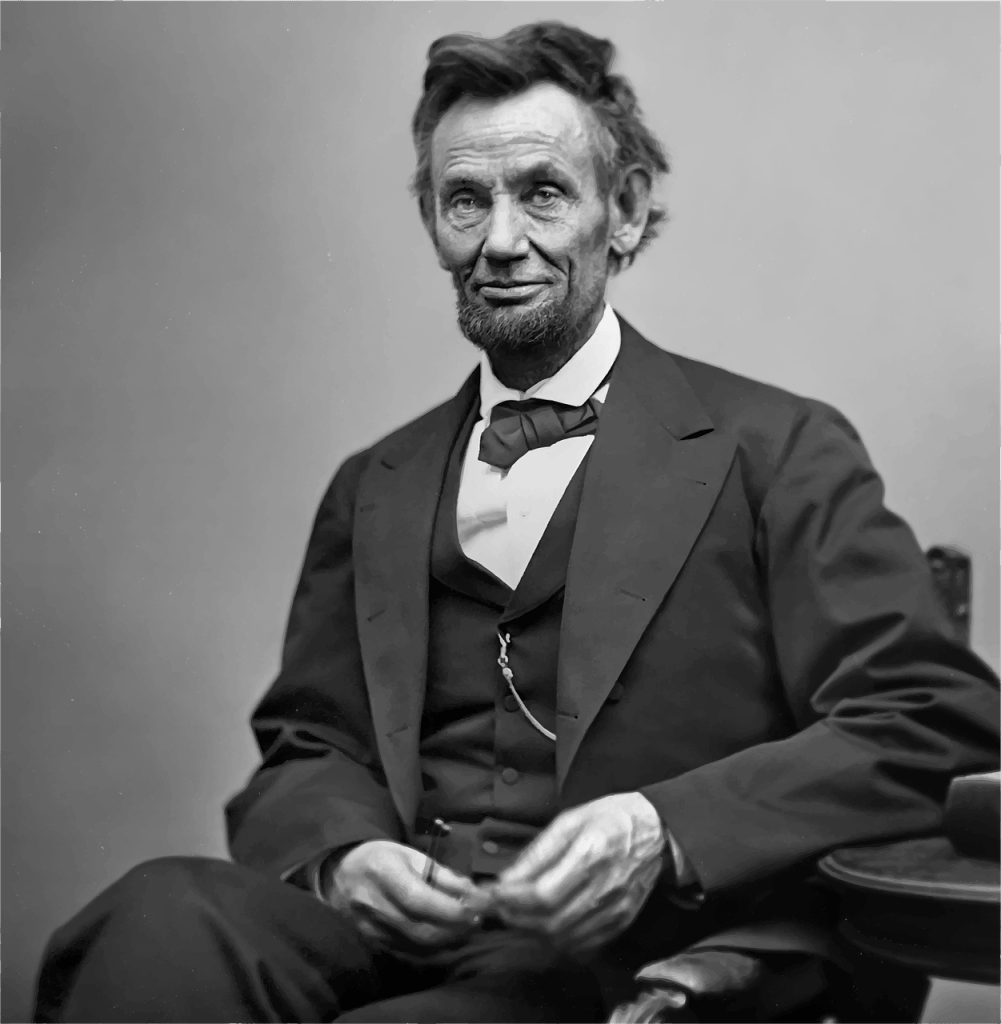

Those who have seen the movie Saving Private Ryan (1998) will recall a scene where the actor playing General George Marshall reads to his staff an eloquent and moving letter of condolence written by President Abraham Lincoln to a Mrs. Lydia A. Bixby during the Civil War. This justly famous epistle, now known as the Bixby Letter, is reproduced below. Who will protest at our quoting it in full here?

Executive Mansion, Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

To Mrs. Bixby, Boston, Mass.

Dear Madam:

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle. I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yours very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln

The letter must rank among the greatest compositions Lincoln ever authored. It is dignified, and imbued with the tenderest of sympathies; it is personal, yet able to reach beyond the confines of death to the noblest of sentiments. Yet it is a great irony that this transcendent piece of prose was, in fact, based on erroneous information provided to President Lincoln. The story behind the Bixby Letter is a fascinating tale, and reminds us that greatness of spirit can emerge even in the unlikeliest circumstances to grasp the most majestic of human truths.

According to William Barton, who researched the Bixby legend and published his findings in the 1926 volume A Beautiful Blunder, the person responsible for sending the information in the Bixby Letter to the War Department in Washington was William Schouler, a state official serving as Massachusetts Adjutant- General during the Civil War. In 1862, after the Battle of Antietam, Lydia Bixby visited William Schouler’s office in Boston. She claimed to have a son who was wounded in the battle, and needed to visit him. She pleaded poverty, and Schouler mentioned her request to Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew; the governor then gave Mrs. Bixby forty dollars to defray her travel expenses.

Apparently, Mrs. Bixby called upon Schouler again in 1864. She showed him what purported to be five letters from five different commanding officers, all informing her of the death of one of her five sons. Schouler was moved by the widow’s circumstances, but took no immediate action on her behalf. The Bixby matter, however, became conflated with another case, and this accident of bureaucratic procedure brought it to the attention of higher offices. A man named James O. Newhall had petitioned the Massachusetts governor for the discharge of one of his five sons. Schouler forwarded the petition on to the governor, and included the following comments:

Pardon me if I add a word in regard to a still more remarkable case than the one presented by Mr. Newhall. Your Excellency may remember that I had the honor two years ago to speak to you of a widow lady, Mrs. Bixby, in the middle walks of life, who had five sons in the Union Army. One of them was wounded at Antietam and was sent to a hospital in Baltimore or Washington. She was very anxious to go and see him, and your Excellency was kind enough to draw your check for forty dollars to pay her expenses, and she made her journey. The boy recovered and joined his regiment again.

About ten days ago Mrs. Bixby came to office and showed me five letters from five company commanders, and each letter informed the poor woman of the death of one of her sons. Her last remaining son was recently killed in the fight on the Weldon railroad. Mrs. Bixby is the best specimen of a truehearted Union woman I have seen. She lives now at 15 Dover Street. Each of her sons by his good conduct had been made a sergeant.

Governor Andrew must have been impressed by both of these stories, for he made copies of each file (Bixby’s and Newhall’s) and forwarded the entire correspondence to Washington, D.C. In his letter to the War Department, the governor endorsed Newhall’s discharge, and added the following words of recommendation:

[I send] 2nd, a report to me by the Adjutant-General of Massachusetts on the case in which he mentions that a widow, a Mrs. Bixby, who sent five sons to the army, all of whom have been recently killed. This is a case so remarkable that I really wish a letter might be written by the President of the United States, such as a noble mother of five dead sons so well deserves.

On October 1, 1864, Colonel Thomas Vincent, the Assistant Adjutant-General in Washington, wrote to Schouler in Boston, asking him to provide additional details on the Bixby case—specifically, the names and units of her five sons who had supposedly died in battle. Schouler had difficulty securing the requested information, but eventually provided the following details on the widow’s sons:

Sergt. Charles N. Bixby, company D, 20th regiment, Massachusetts infantry. Mustered in July 28, 1862. Killed at Fredericksburg, May 3, 1863.

Corp. Henry Bixby, company K, 32nd regiment. Mustered in August 5, 1862. Killed at Gettysburg, July, 1863.

Priv. Edward Bixby, recruit for 22nd regiment, Massachusetts volunteers. Died of wounds at Folly Island, S. C. He ran away from home and was mustered in the field.

Priv. Oliver C. Bixby, company E, 58th regiment, Massachusetts volunteers. Mustered in March 4, 1864. Killed before Petersburg, July 30, 1864.

Priv. George Way, company B, 56th Massachusetts volunteers. Mustered in March 19, 1864. Killed before Petersburg, July 30, 1864. His name was George Way Bixby. The reason why he did not enlist under his proper name was to conceal the fact of his enlistment from his wife.

It would be revealed later that Mrs. Bixby had responded to Schouler with false information. Yet her case eventually landed on the desk of Charles Dana, the Assistant Secretary of War. Dana evidently then passed the information on to the Secretary of War himself, the imperious and ruthlessly efficient Edwin M. Stanton. Stanton’s aggressive demeanor concealed a kind heart, and he almost certainly discussed the Bixby case with President Lincoln at a cabinet meeting. Lincoln, a man of great compassion and magnanimity of soul, would not have required much persuasion to reach out directly to Mrs. Bixby.

In November 1864, Lincoln wrote his letter to Mrs. Bixby in Boston. In the same month, Schouler forwarded to the widow a significant sum of money from the federal government. Schouler gave a copy of the Bixby Letter to the Army and Navy Journal in New York, which published it in December. Mrs. Bixby, however, had not been honest in her initial disclosures to the Massachusetts authorities. Her motivation for lying seems to have been a desire for money and attention.

Charles N. Bixby was in fact killed at Fredericksburg on May 3, 1863. Henry C. Bixby was captured at Gettysburg and honorably discharged in December 19, 1864, later dying in 1871. Edward Bixby did not serve in the 22nd Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers. He never served at all. He was in fact known to be living with his mother in 1876 at 74 Pleasant Street in Boston, eventually dying in 1909. Oliver Bixby was killed in action in Petersburg, Virginia. George Way was captured by the Confederates in 1864 and promptly deserted to the South.

How could such a mistake find its way to the highest office in the land? The answer is exactly what one would expect: the culprit was a mixture of carelessness, bureaucratic ineptitude, and a failure to verify what should have been verified. Not much is known about Lydia Bixby; not even a photograph of her has surfaced. But she must have made a convincing witness. Her story tugged at the heart-strings of both Schouler and Governor Andrew, who were entirely taken in. Schouler claimed to have seen “five” letters from commanding officers about the deaths of Mrs. Bixby’s sons, but it is more likely that he only saw two letters. Both he and Governor Andrew failed to investigate the veracity of her story, and inexplicably compounded their negligence by passing it on, unverified, to Washington.

Perhaps some explanation may be found in the external circumstances the nation faced in 1864. It was an election year, and it was not clear how much longer the war would last. The public mood was tired. Lincoln himself cannot be blamed for the letter; he was dependent on his staff for the information he received, and could do nothing more. Some scholars have speculated that the letter was not even penned by Lincoln, but by one of his secretaries or assistants. No convincing evidence has been advanced to support this theory, and I do not find it credible. The Bixby Letter bears the unmistakable stamp of Lincoln’s prose style, and could have been written by no one else.

It is clear that the Bixby Letter is one of those vaguely comic, yet inexplicably moving, accidents of history. The letter’s deceitful origins do not detract from its beauty and importance. Even if Mrs. Bixby lost only two, and not five, of her sons, is this not sacrifice enough? And who can say at what point grief and depression may cloud factual truthfulness in the mind of an aggrieved widow? There are times when a well-intentioned mistake can grasp the truth more firmly than a rigid adherence to fact. The Bixby Letter ranks among the greatest products of Lincoln’s pen because it managed to distill, in a few sentences, the sentiments of a war-weary but persevering nation.

.

.

Take a look at the new, annotated translation of Cicero’s On The Nature Of The Gods:

You must be logged in to post a comment.