We will discuss the preparation and delivery of the prepared and the extemporaneous speech. I find that, in reviewing the vast corpus of writing about this subject, most authors have devoted their attentions to abstract theories and didactic classifications, instead of practical and effective advice. My comments here are not intended to be an exhaustive study of the art of speech-making; they are meant only to suggest what methods have worked well for me in twenty-five years of trial work before the bar.

The two types of speeches, and their component parts. A prepared speech is one where the deliverer has sufficient time—hours, days, or weeks perhaps—to prepare and refine it. An extemporaneous speech is one that must be given on very short notice, usually within minutes of being obliged to perform the task. Examples of extemporaneous speeches would be those given by lawyers before juries, by politicians before hastily assembled crowds, or by guests at dinners or special events. Contrary to what some believe, there is little fundamental difference between the essentials of these two types of speeches. Both of them contain three—and only three—basic parts: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Pedantic classifiers may wish to add or subtract to these three parts, but in essence, every speech has only three.

The introduction. Every speech has both an objective and a topic. The introduction to a speech functions as a kind of invitation to the audience to perceive the speech’s objective and topic. Perhaps more importantly, the introduction serves to introduce the speaker himself to the audience. His presence and appearance are crucial in determining his credibility. He must “warm up” the audience gradually. He must accustom them to the cadence and flow of his language; he must establish a rapport; and he must draw them into his verbally-created world. One cannot overestimate the importance of this part of a speech. If no connection is established with the audience, the speaker will be unable to deliver his message. The audience will literally shut him off, just as a spigot stops the flow of water: the audience will begin to fidget in its chairs; they will cough and clear their throats; or they will begin to cast their eyes around the room in distracted boredom. These outcomes are fatal to the speaker.

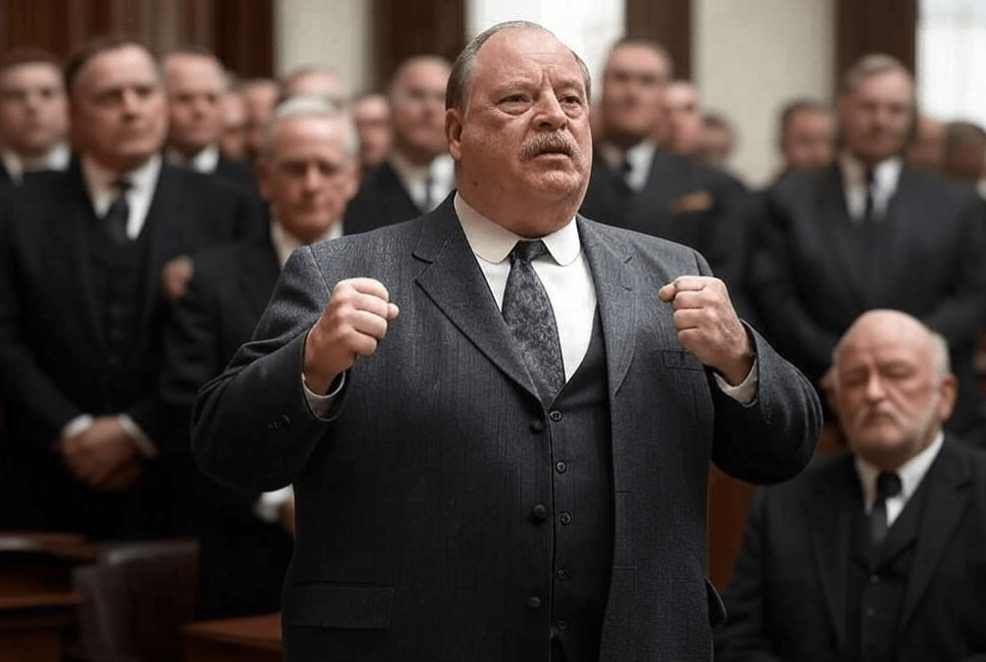

In the introduction phase, it does not much matter what a speaker says. I want to repeat this for those who may not have understood me: it does not matter much what a speaker says in his introductory remarks. Content is not as important as the delivery. The point of the introduction is to establish a rapport, to bring the audience under the speaker’s control, and to plow the ground, so to speak, in preparation for the seeds to be later sown. The speaker should begin slowly and cautiously, his voice measured and smooth. There must be nothing aggressive or bombastic in his introduction. His hand gestures must also be slow and measured, but with this added consideration: hand gestures must also convey authority and power.

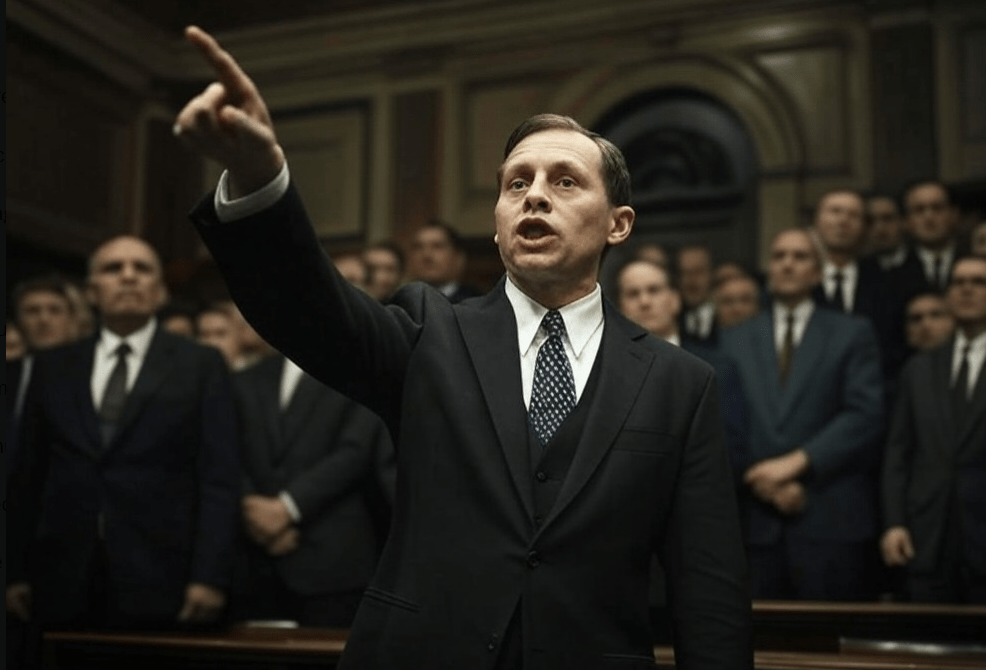

Far too little attention is paid to the nature and quality of gesticulations in speeches. What I have found to be true is this: hand movements must be directed outward, toward the audience, or inward, toward the speaker himself. The axis of movement must be directly between speaker and audience. There should be no movement laterally, to the speaker’s sides, or upward, towards the ceiling or sky. Lateral movements of the hands look weaker than movements to and from the audience. This movement of the speaker’s hands to and from the audience creates, in a way, an axis of connection between speaker and audience. Along this axis will flow, like an electric current, the main points of the speaker’s message to be presented in the body of the speech. Movements of the hands should be crisp and strong, never floppy or limp-wristed.

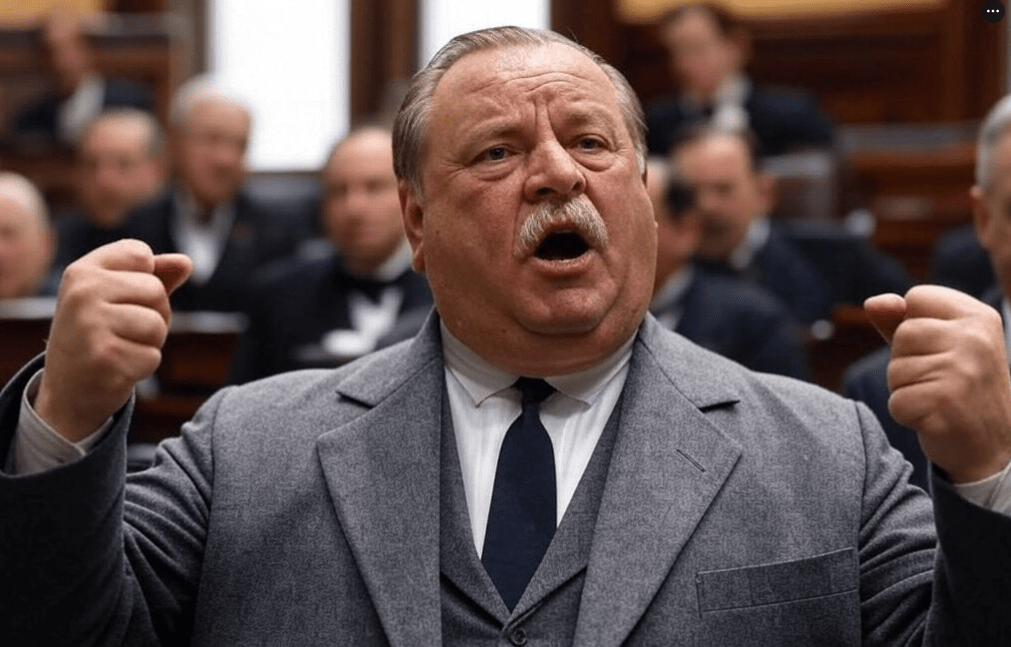

The body. The body of the speech contains the main points and messages of the speech. What is the speaker’s point? What does he want us to think, or to do? What conclusions does he want us to draw about something? These are the questions that should be answered in the body. In practice, the body of a speech can vary widely in length. Some bodies are very short; others will be very long. Everything depends on the nature of the topics being presented. Here I cannot emphasize enough the importance of repetition: attention spans of audiences today are much shorter than they were in, let us say, 1945. A speaker must never lose sight of what points he is trying to communicate, and he must repeat those points in different ways during the body of the speech. Every example, every analogy, every story, every anecdote, and every digression must have this goal in mind: to reinforce the main points that the speaker is trying to convey.

The conclusion. The purpose of the conclusion phase is summarize and congeal all the points made in the body. The conclusion is the speech-maker’s chance to leave his audience with sufficient goodwill towards him and his message. A speech is a form of social interaction, and no social interaction should be closed on a note that is too abrupt. No one wants a door slammed in one’s face; the disengagement with the audience should instead be accomplished with honey and goodwill. It is not necessary to spend too much time summarizing the points of the body of the speech. Several sentences are enough. Nothing can ruin an effective speech more effectively than a ponderous and lengthy conclusion. Less is more. Know when to stop talking; when in doubt, say less and sit down. But what is most important is to end on an emotional note, as this is likely to leave a greater impression on the audience. Quintilian had a word (VI.2.29) for these kinds of emotional invocations: he called them visiones (visions), which he defined as “images of absent things offered to the mind in a way that we picture them with our eyes, and feel them actually to be present.”

Differences between a prepared speech, and an extemporaneous one. I submit that, in terms of content, there is no difference between a prepared speech and one that is delivered immediately. Both types contain the same three parts. What does differ, however, is the manner in which the speaker prepares. In a prepared speech, a speaker will have plenty of time to compose and refine his ideas. He should not waste this opportunity. Some writers believe it is a mistake for a speaker to write out his speech in full before delivery. Quintilian (X.7.32) adhered to this principle; he claimed that the orator should not write out a speech unless he intended to memorize it in full, as such a procedure would reduce a speaker’s agility and vigor at the time of delivery.

I do not agree with this view. In a prepared speech, I have found that writing out the proposed address beforehand was actually an aide to memory. At the time of delivery, I would recall important words and phrases from my pre-written address that could be integrated into the flow of my narrative. The act of written composition etched my mind with what needed to be said, and helped me organize my thoughts for future delivery. There was no cluttering of thought, no tripping over phrases, no unwanted collisions of ideas. Of course, others may differ on this point; and I suppose that one must experiment and discover what method works best.

An extemporaneous speech must be delivered on the spot, always with very little time to prepare. Sometimes there is no time at all to prepare. The only way to prepare for this kind of situation is to do the following: to read a great deal, to write a great deal, and to speak a great deal. The art of oratory is an integrated coordination between mind, mouth, and body; and just as a gymnast cannot master the parallel bars without excruciatingly arduous practice, so must an orator condition himself through years of juggling words and letters in their written and spoken forms. When he has constructed in his mind a silo of stock phrases, words, and verbal constructions, these will flash into his mind when the time to deploy them arrives. He will instantly be able to deploy them as needed, just as a baseball player relies on his muscle memory to field a ground ball hit to second base, or handle fly ball soaring to center field.

It takes time for human body to coordinate rapidly the fluent cooperation of mouth and brain; since the latter operates so much more quickly than the former, and is likely to outpace it, one must have practice to ensure that they function in synchrony. The more realistic one’s training, the better. We are told that Demosthenes would practice his declamations on the beach amid the roar of the surf, in order to condition himself to the raucous noise of the Athenian assembly. To strengthen his breathing, he would run up hills with his mouth full of pebbles. Cicero, despite his formidable memory, was careful to take notes and have them ready for delivery. The only meaningful preparation one can make for an improvised speech is to jot down certain words or phrases as memory aids, and then glance at them as needed while speaking. But here again, one must able to feel the audience, and be attuned to its mood. These, then, are some brief thoughts on prepared and extemporaneous speeches.

.

.

Read more essays on historical and moral subjects in Centuries, which contains all essays from 2020 to 2023.

You must be logged in to post a comment.