We often underestimate the ease with which terrible disasters can accompany our efforts and enterprises. Vigilance tends to lapse with routine; and with time, even the most dangerous cargoes may begin to look benign. Any nation wishing to handle nuclear materials enters a kind of pact with the devil: in return for power and prestige, it can never forget what it is dealing with, and it can never let its guard down. Two lines from the Roman poet Lucan (Pharsalia IX.1020) expresses this idea well:

Tanto te pignore, Caesar,

Eminus; hoc tecum percussum est sanguine foedus.

And this means, “We have acquired you at so great a pledge, Caesar; with our blood this treaty with you was struck.” It may be useful to recount one of the worst nuclear disasters of the Cold War era, one which seems unfortunately to have slipped from our collective memory.

On the Spanish Mediterranean, there is a small town named Palomares in the province of Almería. On Monday morning, January 17, 1966 two American aircraft were carrying out an aerial refueling operation in the region. One plane was a KC-135 jet tanker, and the other was a B-52 bomber which was laden with four thermonuclear bombs. During the operation, one of the B-52’s engines caught fire, and the flames spread to the tanker. The pilots of both aircraft quickly lost control of their machines, and both planes plunged to earth. Seven men died in the accident.

Several miles from the coast, a Spanish fishing captain named Francisco Orts saw a metal tube suspended from a parachute slowly descend in to the sea. This was followed by the sight of three human parachutists falling into the water. Orts rescued them and brought them ashore. The initial response from the administration of U.S. president Lyndon Johnson was guarded and tight-lipped. Within a day of the accident, it was claimed that three atomic bombs had been recovered from the crash site, and an Air Force announcement stated that there was currently no danger to the public. Few placed much credence in these statements, however.

It was the U.S. Navy’s task to recover the bomb which had parachuted into the sea. The salvage operation would eventually become one of the most expensive in American history. The Navy’s salvage superintendent, Commander William Searle, ordered a tug to the area, which arrived on January 18. Minesweepers, landing craft, rescue ships, and oilers soon followed. Overall command of the operation was assigned on January 23 to Rear Admiral William Guest. Technology helped make possible an incredible feat of salvage. Sonar scanning devices and advanced cameras were put to work in aid of the search.

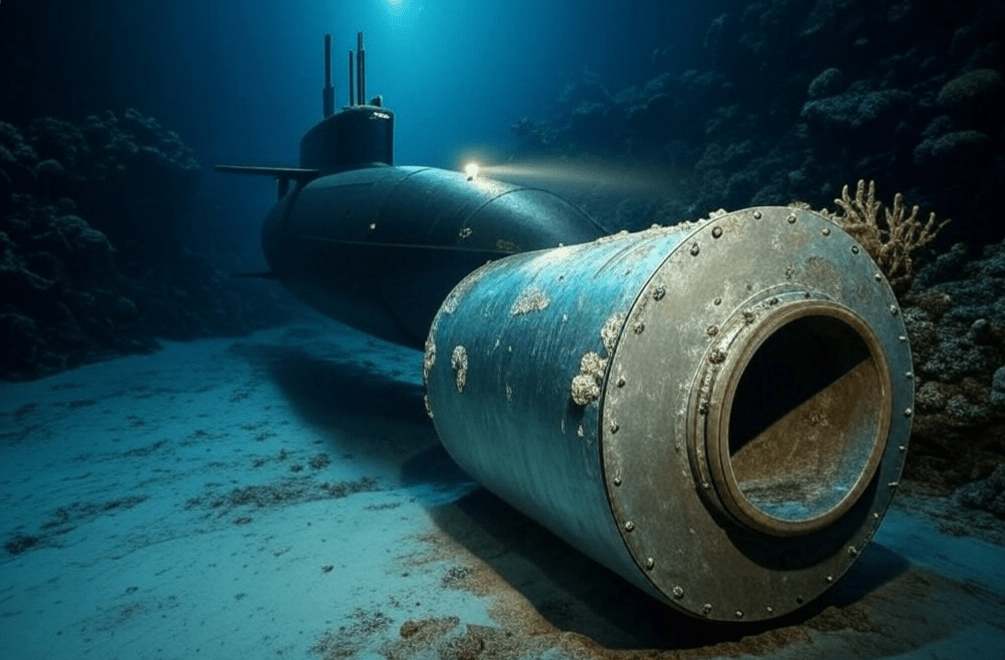

Someone finally thought to consult with Francisco Orts, who had witnessed the bomb fall into the water and sink beneath the waves. It is not often appreciated that experienced fisherman, skilled at reading the signs given by waves, currents, water hues, and reference points on land, can often pinpoint locations at sea with with remarkable accuracy. Orts revealed what he knew, but it was soon apparent that the sea floor in the area where the bomb sank was extremely rocky and uneven. Even worse was the U.S. government’s announcement on March 1 that one bomb was still lost at sea, and that two of the three bombs recovered on land had split open, scattering radioactive material over a wide area of Spanish farmland. On March 15, and with Orts’ direct participation, the bomb at sea was finally discovered. But it was nestled in a precarious location, where one hard jolt might cause its casing to rupture or explode. Miniature salvage submarines photographed the bomb and its precise configuration on the sea floor.

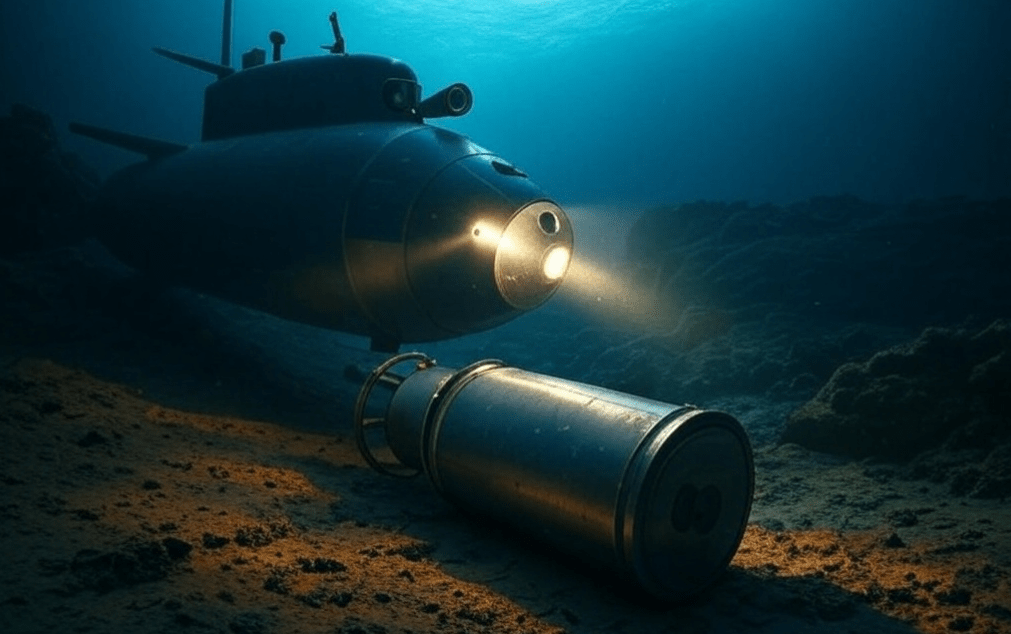

Raising the bomb proved to be extremely difficult. Massy, slippery, and maddeningly cumbersome, it was perched on the edge of a crevice, half buried in mud; and the submersibles were simply unable to get a firm grasp of the metal cylinder. Admiral Guest finally deployed an advanced underwater research vessel called CURV (Cable-controlled Underwater Research Vessel). The advantage of the CURV was that it possessed a strong claw. An Alvin submarine was able to attach an anchor to the bomb’s parachute, and the bomb was raised some distance, but this effort ended in bitter disappointment when the parachute cords snapped and the bomb fell back into the muddy depths.

Storms and squalls caused salvage efforts to be postponed until April 1. After many abortive and frustrating efforts, the CURV descended again and attached itself to the bomb’s parachute. Admiral Guest then ordered the entire affair—the CURV, the parachute, and the bomb itself—to be raised by pulling in the CURV’s power cable. Progress was agonizingly slow: the bomb could only ascend at a rate of about twenty-five feet per minute. When it reached about a hundred feet below the ocean’s surface, scuba divers were sent down to disconnect the bomb’s firing mechanisms and ready the device for the final raising. On April 7th, the project concluded in success. The help of Spanish fisherman Francisco Orts had been essential in identifying precisely where the bomb had fallen into the water. Without him, the bomb might never have been located.

Things on land were far worse, unfortunately. Three atomic bombs had exploded on impact when the B-52 crashed, and radioactive contaminants had been extensively dispersed over an area of about 2.5 square kilometers. Topsoil was stripped away and shipped to the United States for processing. But as recently as 2004, a study of the area showed that significant amounts of radioactive contamination still existed. In 2015, the governments of Spain and the United States signed a bilateral agreement to continue decontamination efforts. To paraphrase the poet Lucan in the lines quoted above, we have acquired our nuclear toys with so great a pledge, and have signed our pact with the atomic devil in blood.

.

.

Read more stories of hazard and daring in the essay collections Centuries and Digest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.