One of the rules of the nineteenth-century whaling industry was that if a captured whale carcass were lost by its owner, it thereafter became the property of the first ship to recover it. After being killed, a whale had to be secured to the side of the whale ship, or towed with ropes; and it occasionally happened that the prize would become untethered from its owner, and float away upon the open ocean. In those cases, the first hand to plant a harpoon in the carcass could claim it as his own.

The following story took place during the nineteenth century near the coast of Greenland. It appears in an anonymous 1840 volume, published in Boston, entitled Book of Shipwrecks and Narratives of Maritime Discoveries and the Most Popular Voyages from the Time of Columbus to the Present Day. Two whaleships sailing near a treacherous ice pack in the north Atlantic spotted, at about the same time, a dead whale bobbing in the water. The captains of both vessels immediately set out for the awaiting prize. An officer with a harpoon at the ready took up position on the bow of each ship. The ships managed to converge on the dead whale at almost exactly the same time; and so intent were they on the aspired prize, that their bows collided, and bounced back some distance.

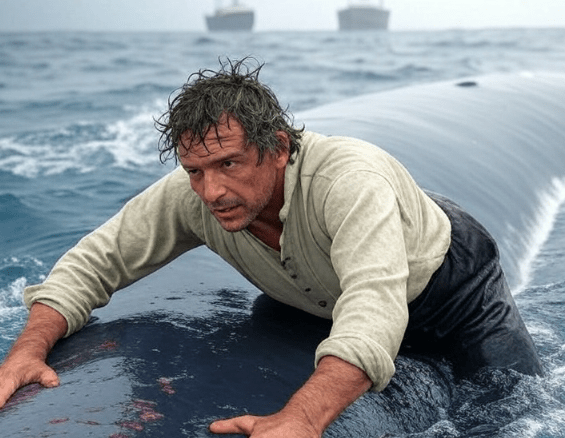

Each officer hurled his harpoon, but neither dart reached its mark. Finally, a daring second mate on one of the ships leaped overboard and swam through the freezing water to reach the whale carcass. He thought that his physical presence on the dead whale would be sufficient to establish his captain’s claim to it. But in establishing possession, guile would eventually defeat audacity.

As often happens at such moments of truth, the valor of the second mate was wasted by the negligence or ineptitude of his captain, who failed to support him. The second mate, with incredible agility, had managed to reach the whale carcass, but could not climb upon it, as its body was bloated to rotundity, and its exterior texture was as smooth as a peeled hard-boiled egg. The mate’s captain failed to sent a small boat to assist the unfortunate man, who by now was beginning to suffer the effects of hypothermia. Instead, the captain chose to waste time trying to moor his ship to a gigantic piece of ice.

Meanwhile, the captain of the other ship sent a boat out to survey the dead whale. The affable occupant of the boat then spoke to the shivering second mate in the water, who by now was clinging precariously to one of the whale’s fins. “Well now, lad, that’s a fine fish you have there!” he exclaimed to the wretched mate. “But don’t you find it very cold?” The mate said that he was indeed suffering greatly in the icy water, and that he would very much like to come into the boat and warm himself. So the freezing mate relinquished possession of the dead whale, and climbed into his competitor’s boat. He was trembling uncontrollably. The occupant of the boat then pulled out his own harpoon, and planted it firmly into the side of the whale carcass, thus claiming it for his ship.

The captain of the mate’s ship eventually found out about this ruse, but it was too late. The prize was now gone to the competitor, and there was no recourse. The captain’s failure to support his second mate meant that his ship ended up with nothing. Had the losing captain shown more initiative, or even a modicum of compassion for his intrepid second mate, who had risked his life to dive into the water and swim out to the whale, the denouement of this little maritime drama would have been quite different.

.

.

Read more about valor and leadership in the annotated translation of Sallust’s Conspiracy of Catiline and War of Jugurtha.

You must be logged in to post a comment.