The pages of the medieval biographer Ibn Khallikan (II.301) contain the following moral anecdotes related to an obscure poet named Abu Al-Hasan Ibn Bassam (?–A.D. 914), who was known by the surname Al-Bassami.

We are told that the elegance and skill of Al-Bassami’s verses were nearly unmatched, but that he was also known for the sharpness of his tongue, and for his inclination to satirize those in positions of authority. These tendencies, of course, did not always serve him well. “None indeed could escape him,” says Ibn Khallikan, “princes and vizirs, high and low, nay even his own father, brothers, and other members of the family had to suffer from his attacks.” But these antagonisms would at times give rise to instructive tales.

On one occasion, Ibn Bassam asked one of the caliph’s vizier’s for a horse. When the vizier refused him, the poet responded with these verses:

Your avarice refused me a vile broken-down horse,

And you shall never see me ask for him again.

You may say that you reserve him for your own use,

But that which you ride was never created by God to be reserved.

[Trans. by M. de Slane]

Our translator tells us that the last line above has a dual meaning. Besides its literal meaning in context, it is secondarily intended to convey the idea that nothing created by God will can remain pure if touched. Some other poignant verses written by Ibn Bassam were these:

When at Sarat, we purloined some nights of pleasure

From the vigilance of adverse fortune, and they now serve

As dates in the sad pages of our life, and as titles announcing

Future joys and hopes to be fulfilled.

“Sarat” is the name of a canal which connected the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. With these lines the poet seems to say that, while memories of past pleasures may evoke sadness at the passage of time, such memories can, at the same time, inspire us to look forward to “future joys and hopes.”

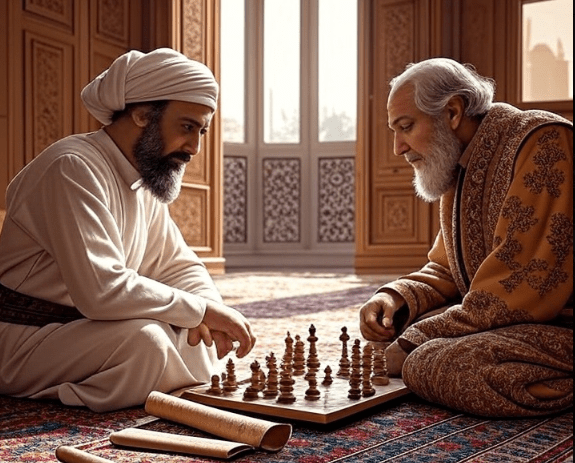

The caliph Al-Mu’tadid was once playing chess when he was approached by one of his viziers. The caliph, deep in thought at the pieces on the board before him, then spoke these philosophically tinged lines:

The life of this one is as the death of that;

In neither case hast thou escaped misfortune.

The caliph’s meaning seems to be this: in some instances, both life and death can be misfortunes, and can, in a way, approach a kind of equivalence. He who wastes his life in folly can hardly be said to have lived at all. When the caliph saw that one of his viziers was standing before him, he told him, “Cut off Al-Bassami’s tongue, so that it may wound you no longer!” The dismayed vizier, believing that the caliph meant this order literally, began to depart, but the caliph gestured him to return, and said, “Do Al-Bassami no harm, but cut off his tongue with kindness. Find him some profitable employment.” The vizier then proceeded to find the poet lucrative employment as a supervisor of bridge tolls. Perhaps the best way to mollify an embittered voice is, in the end, to employ decency and goodness.

.

.

Read more essays containing moral tales and anecdotes in the collections Digest and Centuries.

You must be logged in to post a comment.