The dystopian science fiction film In Time (2011) offers a fascinating and morbid premise. In the future, we are told, time is the ultimate commodity. Everyone is genetically engineered so that the aging process stops at the twenty-fifth year; after this, each person has only one more year of life. A numeric counter is visible on the forearm to show exactly how many years, months, weeks, days, hours, minutes, and seconds each person has remaining on his balance of life.

Additional time is transferred or deducted as one would use currency. A phone call from a public phone might cost a minute. A bus ticket might cost two hours. All of these credits and debits are recorded on the register in each person’s forearm. Time is added or deducted by physical contact of arm against arm, or by arm against a mechanical scanner. Of course, those with wealth are able to accumulate more time on their registers than those lacking in means. A rich man might have hundreds of years on his time counter; a poor man, maybe only a few days or weeks. Every day, then, is a literal struggle for more time to live. It is a horrible conception: those who run out of time drop dead instantly, wherever they may be. Time thieves are always on the prowl, ready to steal years or months from those with large time balances.

The protagonist of the film embarks on a rebellious odyssey against this system. His adventure begins when he encounters a man who, despite having a century of time left on his register, has already lived a very long time, and wants to expire. The man secretly bequeaths our protagonist his massive time balance, and then departs to die, leaving the cautionary message, “Don’t waste my time.” It is an ominous declaration, full of foreboding and portent.

It is undeniable: there is something vaguely horrific about the passage of time. It carries with it a strange mixture of nostalgia, melancholy, and fatalistic resignation. And yet it is not death that disturbs me. It is the remorseless passage of time itself, this ever-widening chasm drawing us further away from our ancestral memories, making us orphans in the insensate void: this pitiless force that grinds even the immoveable mountains into silicate dust. When I first read T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Waste Land,” I was intrigued by its opaque motto, a quotation from chapter 48 of Petronius’s Satyricon. The motto reads in translation:

For in fact I saw with my own eyes the Sibyl of Cumae hanging in a jar; and when the boys said, “What do you want?” she responded “I want to die.”

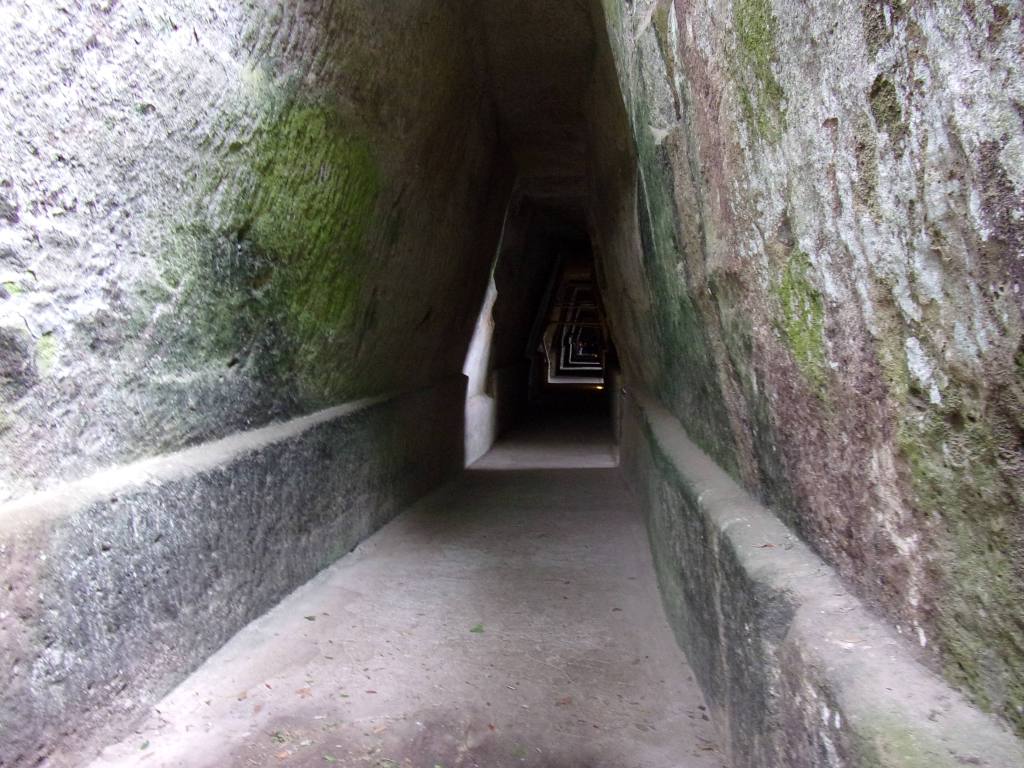

To understand this weird exchange, we must investigate the legends associated with the ancient prophetess known as the Cumaean Sibyl. In the ancient world, temples associated with priestesses and prophecies were an integral part of religion. There were a number of “sibyls” (prophetesses) scattered across the classical world, each one serving the religious needs of the local population. In the Roman world the most famous sibyl was the priestess of Apollo at the town of Cumae. At Cumae was a trapezoidal-shaped grotto leading to an inner sanctum. It can even be visited today. It is a dark and mysterious place, still haunted by the whisperings of a priestess who, one senses, hovers over this lonely outpost.

The tale of the Cumaean Sibyl is among the most unsettling legends encountered in mythology. It appears in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (XIV.129—153). The god Apollo (identified by his epithet Phoebus) approached the Sibyl, a young and beautiful woman, and offered her the gift of eternal life in exchange for taking her virginity. The god told her, “Choose what you want, virgin of Cumae, and you can have your selection.” The girl pointed to a pile of sand, and asked for as many years of life as there were grains of sand in the pile; but, in her haste and immaturity, she forgot to ask that those years be youthful years. So, with the devastating unintended consequences so often found in classical myths, the Sibyl was condemned to live for a thousand years as a decrepit, shriveled hag. As this were not horrible enough, she would also begin to shrink, as age reduced her physical form to an ever-diminishing quantity of matter suspended in a jar:

While I have now spent seven centuries of life, yet, ere my years equal the number of the sands, I still must behold three hundred harvest-times, three hundred vintages. The time will come when length of days will shrivel me from my full form to but a tiny thing, and my limbs, consumed by age, will shrink to a feather’s weight. Then I will seem never to have been loved, never to have pleased the god.

[Trans. by Frank Justus Miller]

Such is the legend. It is a ghastly tale, meant to instruct us on the perils of human vanity. We have been allotted a certain amount of time; it is our task to make productive use of this time on earth in ways that please the gods and our souls. To wish for immortality sets us on a collision course with the will of the gods: immortality is for them alone, and he who aspires to it will be punished severely. Time is a tyrant, but an even-handed one: we can do what we wish with what is given us, but cannot presume to demand more. It is the divine power that sets the clock of life, not us: and no mortal man will be permitted to tamper with its workings.

There is one more tale about the fearful tyranny of time which is relevant in this context. It is a Stephen King short story entitled “The Jaunt,” and it was published in his anthology Skeleton Crew in 1985. In the far future, humanity has mastered the science of quantum teleportation. A person can instantaneously move himself across immense regions of space. As always, however, there rules and limitations to this incredibly powerful technology. A living being can only be teleported while unconscious. If one undertakes a “jaunt” while conscious, the person becomes trapped in a kind of interdimensional limbo for millions of years.

Experiments were conducted on convicted prisoners who volunteered to jaunt while conscious; and in every case, when the participant emerged from the trip, he died nearly instantly of shock, having been suspended in a void for an eternity. What seemed an instantaneous trip to onlookers, was in fact an ordeal of millions of years for the participant. It was as if a prehistoric insect were trapped in amber for an eternity, but instead of being dead, it was aware of what was happening to itself, and of the crushing passage of centuries. I will not reveal the plot or conclusion of the story; that is for the reader to discover. But let us say that the myth of the Cumaean Sibyl survives in the modern era, and its warning still resonates.

.

.

Read more about the workings of human and divine power in the new translation of Cicero’s On The Nature Of The Gods.

You must be logged in to post a comment.