In 1849, the young Fyodor Dostoyevsky was arrested for anti-tsarist activities and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted by the tsar at the last instant, and he was instead given a four-year term in a prison camp in Siberia. From this shattering experience came his semi-autobiographical novel The House of the Dead, which was published in 1860.

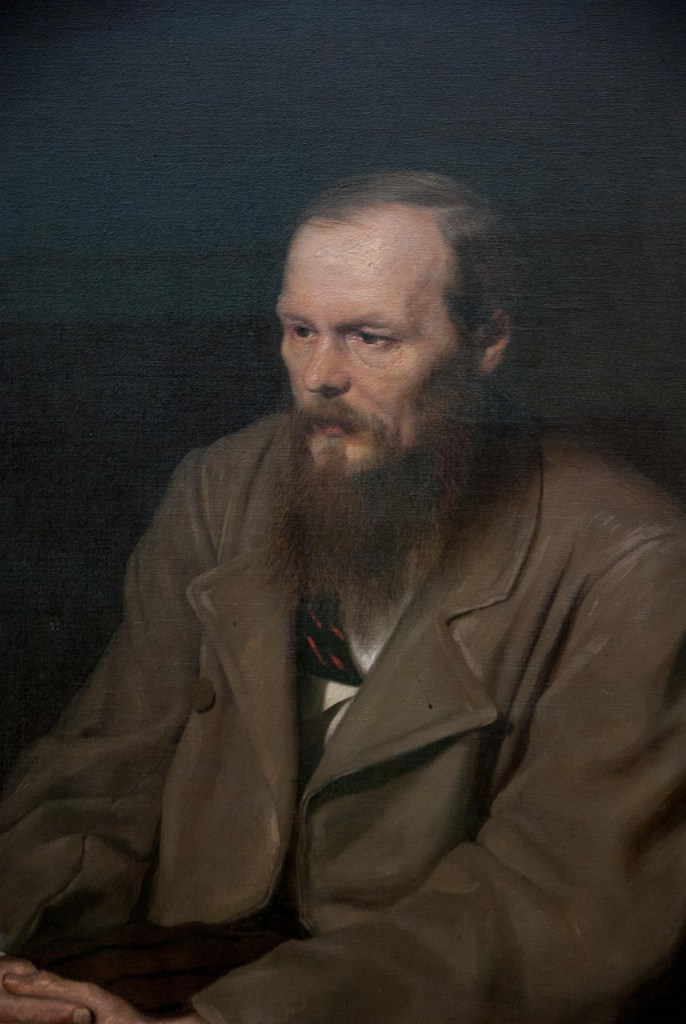

Dostoyevsky loves to explore the psychological motivations and yearnings of his characters. No other novelist probes as deeply, and with as much sympathy and insight, into the minds of his subjects. There is in him this tension between a genuine love of humanity, and a cautious guardedness that springs, perhaps, from having been stung one too many times in his human interactions. This master psychologist somehow manages to be both a detached observer and an intimate participant at the same time. He never glorifies the “unfortunates” (the Russian term for convicts) but, by seeking to understand their motivations and sufferings, anoints them with a quiet dignity that gives their lives moral significance.

Chapter 9 of The House of the Dead contains a tale called “Baklushin’s Story.” Baklushin is an inmate who tells the novel’s narrator, frankly and without equivocation, the story of how he came to be in prison. The name of the novel’s narrator is Alexander Petrovich Goryanchikov, and we can be assured that his views reflect exactly those held by Dostoyevsky.

In the city of Riga, Baklushin tells the narrator, there was a sizeable German population. Baklushin fell in love with a German girl named Louise, who reciprocated his feelings. Unfortunately for him, the girl was involved with a wealthy, older German watchmaker named Schultz, who was also a distant relative of hers. Schultz eventually tells Louise to stop seeing Baklushin. Consumed with unresolved passion, the jilted Russian eventually decides to confront Schultz at his place of work. Before doing so, he puts an old pistol in his pocket. He confronts Schultz amid a group of guests, and impetuously threatens to shoot him. In a fit of perversity and rage, Baklushin pulls out the firearm and, in full view of the assembled guests, presses it against his victim’s head. When Schultz challenges him, Baklushin carries through with his threat, and takes the old man’s life. It is a horrifying and senseless murder, a product of jealousy, ignorance, and blind rage.

The story is told with a mixture of bluster and earnestness, as if Baklushin were desperately trying to relieve himself of the tale’s terrible burden. Dostoyevsky has several motivations with Baklushin’s story. He wants, first of all, to remind us just how easily crimes can occur without any adequate justification. Men are moved by dark passions, and in the absence of the restraints of morality and the virtues, these passions can consume everything in their midst. Lives can be destroyed in an instant, leaving even the survivors permanently affected.

But all is not darkness. For Baklushin is presented in some ways as a sympathetic figure. We condemn his conduct, but can understand that his inability to control his volcanic emotions was what doomed him. The reader also feels a sense of relief at Baklushin’s honesty in taking responsibility for what he did, instead of trying to point his finger at others. Despite the monstrous nature of his crime, Baklushin is still a human being deserving of basic humanity. Dostoyevsky’s complicated views of criminal intent mirror my own, which have been shaped as a criminal defense lawyer during the past twenty-five years. Given the right set of circumstances, crimes—even terrible crimes—can be committed by almost anyone.

This is perhaps the most sobering realization an attorney makes very early in his career. Some criminals are fools, some are rogues, and others idiots. A small number may be said to be truly wicked. But most are hapless nonentities lacking impulse control, or a sense of the consequences of their actions; they failed to police their emotions, and led themselves down irreversible pathways. This is not to excuse their conduct; it is only a way of explaining deviant behavior. Dostoyevsky understands this truth. In a digression in Chapter 8, reminds us that even the worst of men are deserving of basic humanity:

And indeed the lower ranks are irritated by any condescending off-handedness, any disdain that is shown to them. There are some who think, for example, that as long as one feeds a convict, looks after him well, does everything according to the law, the matter is at an end. This is a mistaken view. Everyone, whoever he is and however lowly the circumstances into which he has been pushed, demands, albeit instinctively and unconsciously, that respect be shown for his human dignity. The convict knows he is a convict, an outcast, and he knows his place vis-a-vis his superior officer; but no brands, no fetters will ever be able to make him forget that he is a human being. And since he really is a human being, it is necessary to treat him as one…Human treatment may even render human a man in whom the image of God has long ago grown tarnished. It is these “unfortunates” that must be treated in the most human fashion. It is their salvation and their joy. [Trans. by David McDuff]

The closer we examine things, the more complicated they become; and the greater the power of our microscope’s magnification, the more complex the objects of our study become. Within the human soul exist both moral duality and unresolvable contradictions. All of us wrestle with this fact; and it is only the civilizing influence of moral training and study that can control the impulses inhabiting our darker recesses. Some succeed in taming these passions, while others do not. Perhaps the most that can be said about crime and punishment is contained in that old adage, There but for the grace of God go I.

.

.

Read more about the consequences of our actions in the new, annotated translation of Cicero’s On Moral Ends.

You must be logged in to post a comment.