We are told that the word dystopia first entered the lexicon in 1868, when John Stuart Mill used it in a parliamentary speech. The first dystopian novel is somewhat open to debate, but many consider H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, first published in 1895, to be a strong candidate.

The Time Machine is probably my favorite Wells novel. It is more a science fiction allegory than a dystopian novel. It has a transfixing and unearthly power, a deceptive simplicity that conceals awesome and fateful themes. Its final ghastly images, in which the narrator watches monstrous crabs scuttling along a stagnant, blood-red shoreline in the earth’s remote future, force the reader to contemplate the inescapable Heraclitean cycle of creation and destruction. What is much less well known is that Wells wrote another book that can more properly be considered a “dystopian novel,” as that term is understood today. The book’s name is When the Sleeper Wakes, and it was first serialized in The Graphic magazine from 1898 to 1899. It is a flawed but underappreciated work which remains relevant to this day.

I should note that the original novel underwent a number of revisions by the author when it was republished in 1910 under the title The Sleeper Awakes. It is not uncommon for writers to make these kinds of changes. Some additional material was added, some was taken away, and several chapter titles were changed. But the core of the story remained consistent. Modern readers may find the outlines of the tale vaguely familiar, as some of its plot elements have become mainstays of the dystopian genre.

A Victorian-era Londoner named Graham falls into a coma after taking a dosage of insomnia drugs. The coma becomes, in effect, a state of suspended animation that lasts for over two hundred years. When Graham awakes, he is told he is the world’s wealthiest man. During his period of hibernation, his investments were managed with such shrewdness that his net worth increased with exponential potency. There is now one global society, and it is a highly-controlled nightmare. The rich inhabit their pleasure palaces, while the poor toil in perpetual servitude. London has become a sprawling megalopolis, inhabited by denizens seething with resentment and grievance.

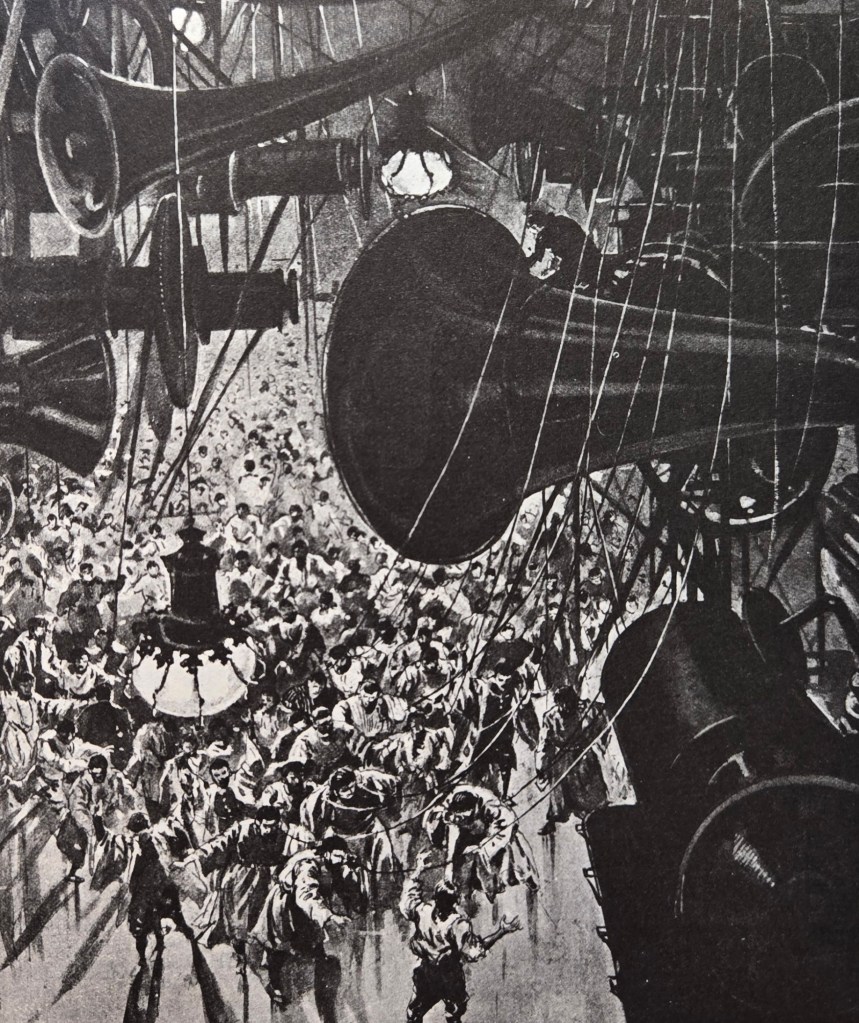

The world is governed by an entity called the White Council, which uses Graham as a kind of symbol and figurehead. Graham is known as The Sleeper, and is an object of reverence for the populace. The White Council, of course, rules for its own benefit, not for the benefit of humanity. Constant propaganda plays a vital role in maintaining control over the restive population. Public machines (“babble machines”) emit a constant stream of disinformation, all of which is designed to prevent the masses from identifying the causes of their misery. Order is also enforced by a foreign police force, apparently imported from Africa. In this passage, Wells describes the omnipresent babble machines (Chapter 20 in the original serialized edition):

As he and his companions pushed their way through the excited crowd that swarmed beneath these voices, towards the exit, Graham conceived more clearly the proportion and features…Altogether, great and small, there must have been nearly a thousand of these erections, piping, hooting, bawling and gabbling in that great space, each with its crowd of excited listeners, the majority of them men dressed in blue canvas. There were all sizes of machines, from the little gossiping mechanisms that chuckled out mechanical sarcasm in odd corners, through a number of grades to such fifty-food giants at that which had first hooted over Graham.

Graham eventually crosses paths with a charismatic figure named Ostrog, who presents himself as a revolutionary. Ostrog and Graham combine forces and eventually take power away from the White Council, but the victory is short-lived. Ostrog, who has concealed his true nature and character, is now revealed to be just another power-hungry opportunist. The new regime, it turns out, is no improvement over the old. Graham decides to lead his own revolt against Ostrog, and takes to the air in a flying machine called an aeropile. The descriptions of aerial combat in the novel read like an uncanny presentiment of the dogfights of the First World War. The novel ends on an ambiguous note; we are not informed of the conclusion of the contest between Graham and Ostrog.

Is When the Sleeper Wakes worth reading today? It is. It is remarkable how many things Wells accurately predicted. The overpopulation of cities, the gross disparity between rich and poor, the depopulation of the countryside, the control of society through ceaseless propaganda, the cynical nature of power, and the hypocrisy of self-proclaimed liberators: all of this he understood and envisioned. And yet, in the midst of all this despair, all this horror, Wells still left room for a guarded optimism. Graham, despite all the unfavorable odds he faced, still elected to rebel. He refused to wallow in despair and inaction; he refused to allow the tyrant-in-making, Ostrog, to consolidate his tyranny. The populace, though poor and unsophisticated, understood the difference between freedom and slavery. When given the choice, they chose to fight for freedom. In this sense, When the Sleeper Wakes can be seen as an ode to hope; and perhaps humanity, when faced with stark choices, is capable of more nobility and greatness than minds accustomed to lethargy and ease can conceive.

.

.

Be sure to take a look at the new, annotated translation of Frontinus’s Stratagems, a classic of military theory.

You must be logged in to post a comment.