New York City, like all large cities, has experienced a number of riots in its long history. But the Draft Riots of 1863 surpassed every other upheaval, before or since, in unadulterated ferocity.

To understand its origins, we must look to the social and political conditions of the era. New York in the 1860s rested on a deeply unstable social order. Its population was about 800,000, and sixty percent of the city’s wealth was controlled by only 1,600 prosperous families. For the well-to-do, life was very good. The picture was a decidedly different one for the masses, however. By the late 1840s, real estate tycoon John Jacob Astor was the city’s richest landlord. Before he ventured into real estate, Astor had amassed tremendous wealth through various ventures, including trading liquor and guns to American Indians for furs, plundering precious woods from the Hawaiian Islands, and smuggling opium into China. Astor acquired huge tracts of real estate in New York City at foreclosure sale prices during the Panic of 1837—in reality, an economic depression—and converted these property holdings into miserable accommodations for the poor.

The European immigrants occupying the lower rungs of the social ladder had few options. With scant access to health care and education, their ranks were ravaged by diseases like cholera, smallpox, and typhoid, and their communities plagued by crime and ignorance. The immigrant Irish community numbered around 200,000 (one-fourth of the city); they tended to be more politically aware than immigrants from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean region, and they were deeply dissatisfied with current conditions. Irish volunteers had contributed significantly to the Union Army, and had sustained high casualties. President Lincoln’s introduction of conscription appeared to them both as an insult to their patriotism, and as an underhanded method of forcing the poor to fight a rich man’s war. New York City industrialists had grown rich from the Southern cotton trade, and yet their sons never seemed to die on the battlefield. This was an era in which wealthy men could pay a substitute to take their place in the ranks. Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, Chester A. Arthur, and the fathers of both Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt, had all hired substitutes. And there were other ways a man could avoid military service. If he could raise $300 in cash, he could purchase his way out of conscription. This sum constituted more than the annual wage of a manual laborer. It is not surprising that the unfairness of the conscription regime contributed to the working class’s alienation from a system that seemed designed to keep them down.

As the Civil War dragged on, inflation destroyed the earnings of Irish laborers and maids, and this generated a seething resentment against the rich, who always seemed to be able to float above the squalor created by their own avarice. During the war, prices had risen by 43%, while wages had seen only a 10% increase. Other issues chafed as well. The Irish had, in general, little love for the Republican Party and its administration in Washington, which they tended to identify with plutocrats and landlords. Having endured their own sufferings under a repressive colonial system, many poor Irish found it difficult to identify with the cause of black emancipation, which increasingly seemed to be a primary war objective. Ferocious competition for limited resources meant that any perceived advantage for one group was seen as harming another. White laborers were inclined to fear that the demise of slavery would result in a surge of free blacks into New York City, with whom they would then be forced to compete at a disadvantage.

To explain is not to condone, and none of this should be interpreted as excusing the perpetrators of the riot or their terrible crimes. Yet it is impossible to understand the causes of the Draft Riots without discussing the social and political conditions that prevailed in New York City of July 1863. It was a social tinder-box which required only a small spark to ignite.

The Enrollment Act of 1863 mandated conscription, and the draft lottery was scheduled to begin on July 11, 1863. New York governor Horatio Seymour was worried about the possibility of mass violence; he asked President Lincoln to postpone the implementation of the draft until more federal troops could be assigned to the city, but his concerns were ignored. When on July 12 the names of the conscripts were published in city newspapers, mass demonstrations against the federal government began. Huge crowds carrying banners that read “No Draft!” moved through the city’s major thoroughfares. As often happens, miscreants, hooligans, and criminal elements found that they could use the demonstrations as cover to indulge their destructive impulses and racial hatreds. Gangs of toughs rampaged through Manhattan, smashing stores and destroying civil infrastructure. A police captain was murdered by a mob, and an arms depot owned by Mayor George Opdyke was plundered.

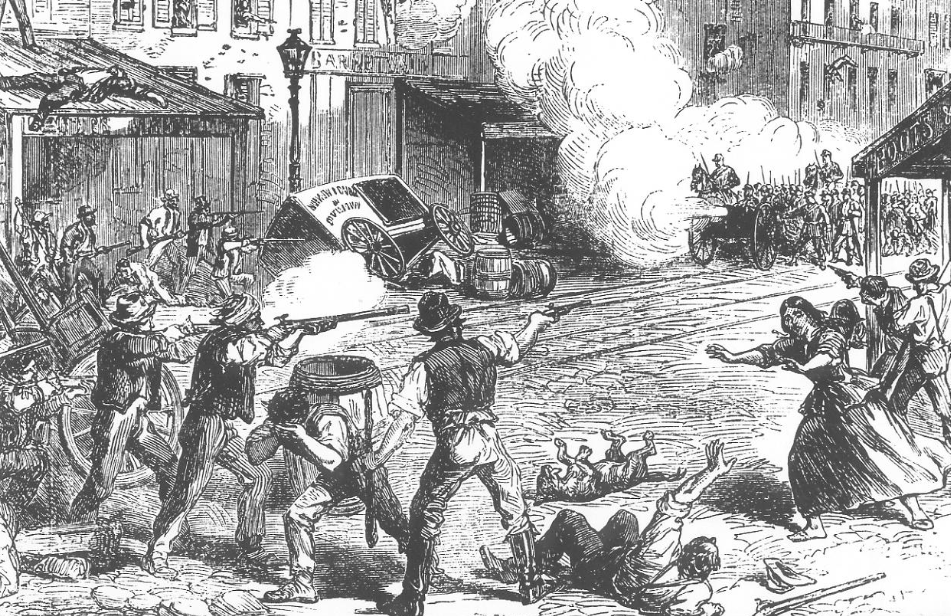

The city’s black population numbered around 10,000, and all of them became potential targets. Also targeted were anyone who looked wealthy, any police officer, or anyone who attempted to intervene to stop the expanding orgy of violence. The city’s small police force was overwhelmed, and could not cope with the scale of the crisis. After the first day, the riot began to take on the characteristics of an urban insurrection: barricades were built, railroads and telegraph lines were destroyed, and symbols of the establishment were ransacked. The Customs House and the Treasury office very nearly came under attack. Weapons were seized from arms depots, newspaper offices were burned, and soldiers in uniform were assaulted. The Colored Orphan Asylum at Forty-Fourth Street was burned to the ground.

A police account of the riot published in 1863 describes one scene, which looks very much like urban warfare:

On Tuesday morning, at 6 o’clock, with two hundred and fifty men, Inspector Carpenter proceeded to Second Avenue; on reaching it at Twenty-first Street the force were met with groans and hooting, but by no assault, until passing the block between Thirty-second and Thirty-third Streets; here the rear of the force was suddenly assailed with showers of bricks, stones, and other missiles, from the roofs and windows of the adjoining houses; several of the men were knocked down; two were badly injured; the Inspector instantly halted his command, and directed a force of fifty to storm the houses, enter to the roofs, and render hors du combat [sic] every one engaged in the assault. The order was obeyed with a cheer, the locked and barricaded doors broken in and forced, the premises entered, all resistants knocked down, the roofs reached, where were found a large number of the assailants. Here a hand-to-hand and desperate fight ensued, in which the ruffians were overcome and several fearfully punished; many were left lying on the roofs, others fled through the scuttles only to receive the clubs of the officers in wait below, and those who escaped into the street were met by the reserve, who administered severe retribution. The victory was complete, the houses thoroughly cleared, and the missiles cast from the roofs into the street. [Barnes, David, The Metropolitan Police: Their Services During Riot Week, (1863) p. 16]

Governor Seymour finally ordered reinforcements into the city. By July 17, the Seventh Regiment had arrived, and heavy artillery had been deployed. Two volunteer regiments from Fortress Monroe joined the occupation. New York City became an armed camp. The military commander, General John A. Dix, suspended habeas corpus and formed a security force to arrest on sight anyone suspected of plotting a renewal of the violence. The precise death toll is not known. Most accounts number it above a hundred, but real total is probably much higher. The dead included police officers, soldiers, innocent victims, and rioters (even women and children). At least eleven blacks were lynched. Yet despite the horrific violence, the city recovered quickly. The draft was resumed in August without incident, and by April 1865 the war was over. The Draft Riots of 1863 stand today as a chilling reminder that unstable social conditions, if left unaddressed, carry the seeds of potential calamity.

.

.

Take a look at Digest, the complete collection of essays from 2020 to 2023, which covers topics in moral philosophy, history, literature, and biography.

You must be logged in to post a comment.