Canto XXVI of Dante’s Inferno takes place in the eighth bolgia (ditch) of the Eighth Circle of Hell. Here reside those guilty of providing fraudulent or deceitful counsel. In life, these souls used their persuasive abilities to harm or destroy others; and, in keeping with Dante’s attention to the principle of contrapasso, their punishment in Hell fits their crimes during life. As they once used their tongues for malicious speech, so in the afterlife are their souls “tongued” forever with flame.

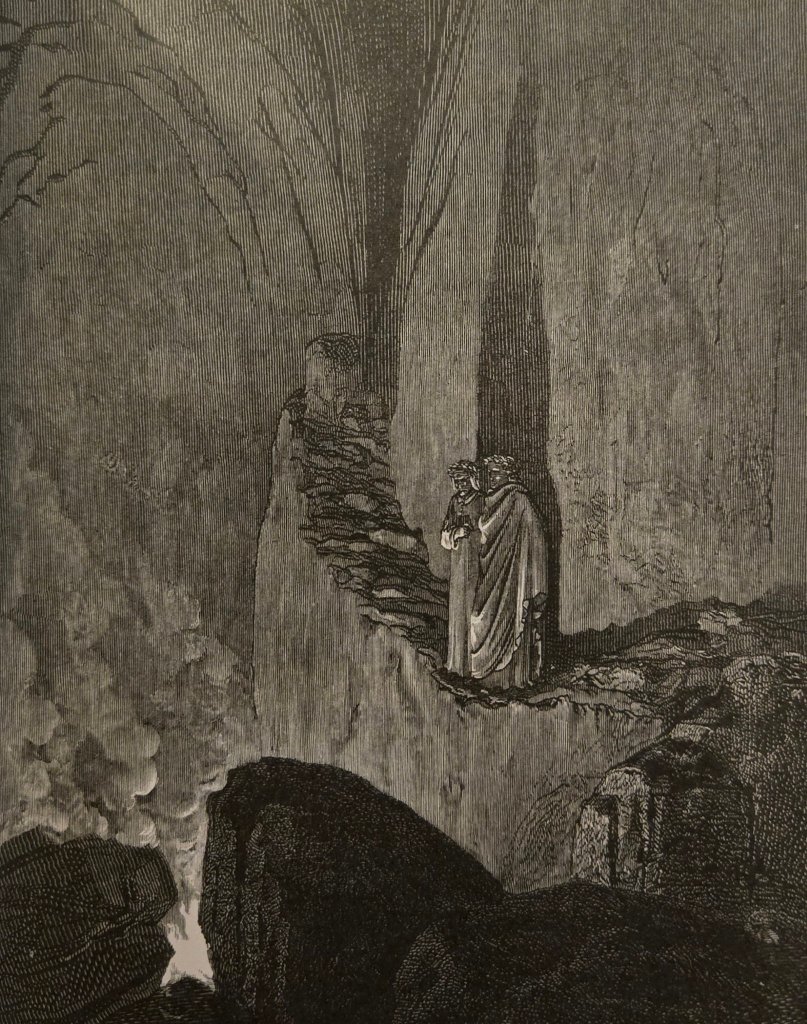

Dante arranges the scene, as always, with unforgettable clarity. He ascends a precipitous rock with his trusted guide, Virgil, and stands upon a bridge:

I stood upon the bridge uprisen to see,

So that, if I had seized not on a rock,

Down had I fallen without being pushed.

And the Leader, who beheld me so attent,

Exclaimed: “Within the fires the spirits are;

Each swathes himself with that wherewith he burns.”

[Longfellow’s translation XXVI.43—48]

From this perch they are able to see below a multitude of flickering flames, as luminous as fireflies on a summer night, each one representing a lost soul in torment. Virgil notices two heroes of the Trojan War, Odysseus and Diomedes; they now face damnation due to their unashamed duplicity throughout their careers. Readers of the Homeric poems will recall that Odysseus never seemed to speak a true word in his life. He helped plan the ruse of the Trojan Horse; he had a hand in the blasphemous theft of the Palladium, the statue protecting Troy; and his later voyages through the Mediterranean are marked by lies, conniving, and trickery. It may have once been entertaining, but it carries a fateful consequence. This fact may contradict our modern favorable estimation of him as a character in literature, but Dante sees things differently: for him, Odysseus was a transgressor, a liar, and a trickster, and he must pay the price for the life he chose to live.

Each swathes himself with that wherewith he burns.”

Dante wishes to converse with Odysseus, but Virgil considers this ill-advised, since the Greek would likely not be inclined to speak to a “Latin,” that is, a descendant of the Trojan race. So Virgil speaks to the flickering tongue of flame that once was Odysseus, and here begins one of the most famous passages in Western poetry. Odysseus describes his wanderings after the Trojan War, and tells of his inability to settle down to a life of domestic predictability. His ties to his aging father Laertes, his wife Penelope, and his son Telemachus, begin to fray—all these connections could not persuade him to lay down his boat-cloak. He had to take to the open ocean. So he gathered together his former comrades—old men by now—and they set sail for lands and shores remote. He tells his friends:

Consider ye the seed from which ye sprang;

Ye were not made to live like unto brutes,

But for the pursuit of virtue and of knowledge.

[XXVI.118—120]

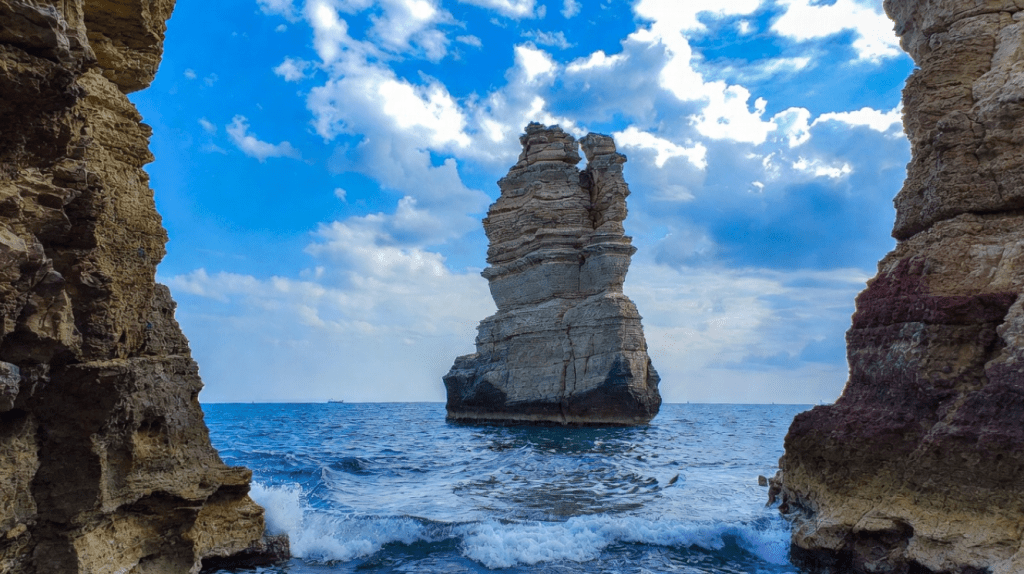

They sailed west across the Mediterranean, through the Straits of Hercules (now known as the Straits of Gibraltar), and into the vast expanse of the Atlantic. For five months they penetrated the southern hemisphere until their ship was wrecked by a storm, and they all perished.

In Dante’s day there was an idea that venturing beyond the Pillars of Hercules was an affront to the divine limits that God had set for mankind. For the medieval mind, the Pillars were not just a physical barrier: they symbolized a certain moral or metaphysical limit as well. Man could go so far, but no further. This idea was encapsulated in the Latin phrase ne plus ultra, which means, “no more beyond.” It is, of course, easy today to view this idea with contempt. After all, a hundred and fifty years after Dante’s death, intrepid voyagers did, in fact, venture beyond the Straits of Gibraltar to discover new continents. Dante himself may even have been aware of the ancient Phoenician circumnavigation of Africa, which is attested to in Herodotus (IV.42). Although the first Latin translation of Herodotus would not appear until the 1470s, and Dante could not read Greek, it is likely that bits and pieces of the Father of History circulated in Italy through manuscripts, oral traditions, and scholarly intercourse.

As we have said, it is easy for us today to scoff at the idea that the Straits of Gibraltar represented a kind of ultimate limit. We like to believe we know so much more than our remote ancestors. But perhaps Dante and his era were in no way as ignorant as we would like to believe. Perhaps Dante is trying to communicate a moral truth: that it is hubris and arrogance for man to assume he knows all, can do all, and can venture into any seas he wishes. Just as the speed of light imposes a kind of cosmic speed limit, perhaps there also exists an ultimate moral limit for man.

Odysseus, in Dante’s view, represents the idea that those who arrogantly assume they can cross all boundaries will, eventually, be made to learn that there are such things as limits. There is a limit to man’s ability to comprehend the universe. There is a limit to how far a man can tamper with Nature. Those who cross such limits commit offenses against Nature, and, in Dante’s view, challenge God. And for this they must be severely punished. It is an idea as old as literature; only by Dante’s time Christian theology had supplanted the moral lessons imparted by Greek drama and the great heroic epics. But the lesson is the same.

We should note that Dante is not saying that the quest for knowledge and virtue is inherently bad: certainly not. He is no timid retrograde, no shriveled and dogmatic intellect afraid to venture outside his front door. He does not wish to keep us frozen in technological time. What he means is that knowledge and power disconnected from principles of humanity and moral goodness are offensive to God, and will inevitably be punished. The principle of ne plus ultra exists, then, not as a physical barrier, but as a moral and metaphysical one. It is, in a sense, the same lesson imparted by Cicero’s On Moral Ends.

Many who hold positions of power and authority today have visibly transgressed, or seek to transgress, those divine limits that have been imposed on us. Narcissistic billionaires believe they can tamper with the secrets of human biology and development, and cherish the notion that they have the right to construct a race of machines powered by artificial intelligence. Political leaders believe they can discard the rule of law and tradition at will, and arrogate to themselves powers that even the dictators of old never dared to acquire. Around us we see a social order saturated with ignorance, arrogance, contempt for the limits imposed by reason, tradition, and law, and a conscious, steady march towards destruction. If there is a moral limit for man—and I am certain that there is—we are coming perilously close to crossing it, if we have not already done so. It is not man’s concern to tamper with the workings of Nature; it is not man’s place to assume divine powers. It is an offense against Nature to disrespect, or to tamper with, the inheritance She has bequeathed us. And if Dante is correct, sooner or later a heavy price will be paid for our presumptions.

.

.

.

Read more about the nature of the ultimate good, and ultimate evil, in the new translation of Cicero’s On Moral Ends.

You must be logged in to post a comment.