I read recently a fascinating tale of nautical survival. In 1965, six teenage Tongan boys were shipwrecked on the uninhabited island of Ata in the Tongan Archipelago of Polynesia. After stealing a boat, they had encountered a storm which deposited them on the island without any means of communication with the outside world.

Instead of descending into a Lord-of-the-Flies-like savagery, the boys cooperated closely to ensure their mutual survival. They lived for fifteen months on the island until their rescue by an Australian fisherman. They were perfectly healthy at the time of their deliverance. This story may be a reminder that zero-sum competition is not inevitable, and that determined efforts at cooperation and mutual aid will bear fruit. On the other hand, perhaps the lesson imparted by this instance is narrow in scope. The Bounty mutineers, for example, who landed at Pitcairn’s Island in 1790 had the opposite experience, fighting and killing each other over resources and women. It is not easy to know for certain. Even the wisest of philosophers cannot hope to circumscribe the limits of human ingenuity in acquisitiveness and slaughter.

Is the zero-sum game inevitable in every instance? Are we destined to squabble amongst each other over every available resource, until nothing, including us, remains? Must one’s gain always represent another’s loss? Is it inevitable that, as Herman Melville says in his war poem “Apathy and Enthusiasm,” human affairs will be like

The Iroquois’ old saw:

Grief to every greybeard

When young Indians lead the war.

We should first state what we mean by the term “zero sum game.” The phrase describes a situation in which resources are finite, and where the acquisitions of one player result in a detriment to another. Suppose you and I peer into a box of ten oranges placed before us. If I reach into the box and remove seven of them for myself, you are of course left with only three. My gain of seven is your loss of seven; and if we sum those two quantities (7 added to -7), the result is zero. This, at least, is the theory.

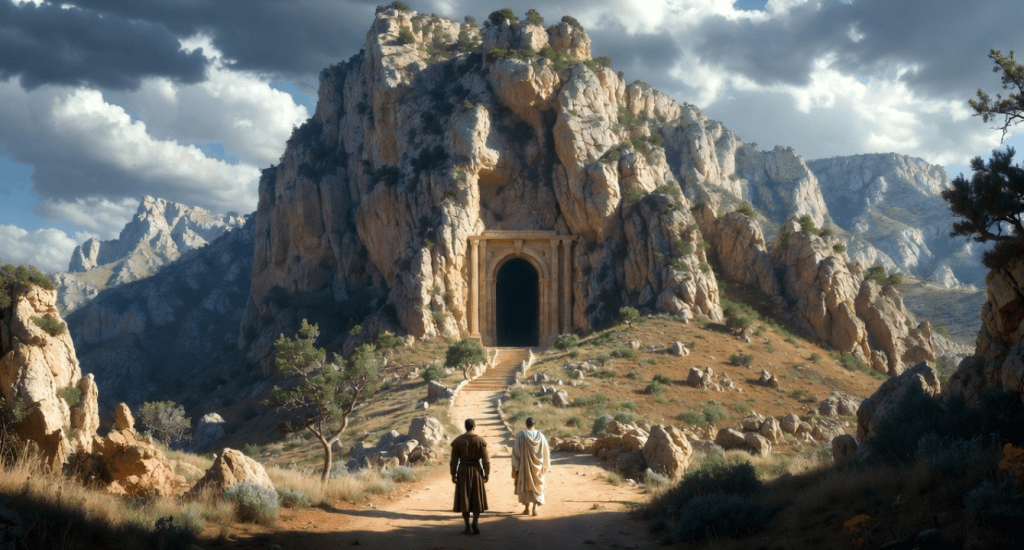

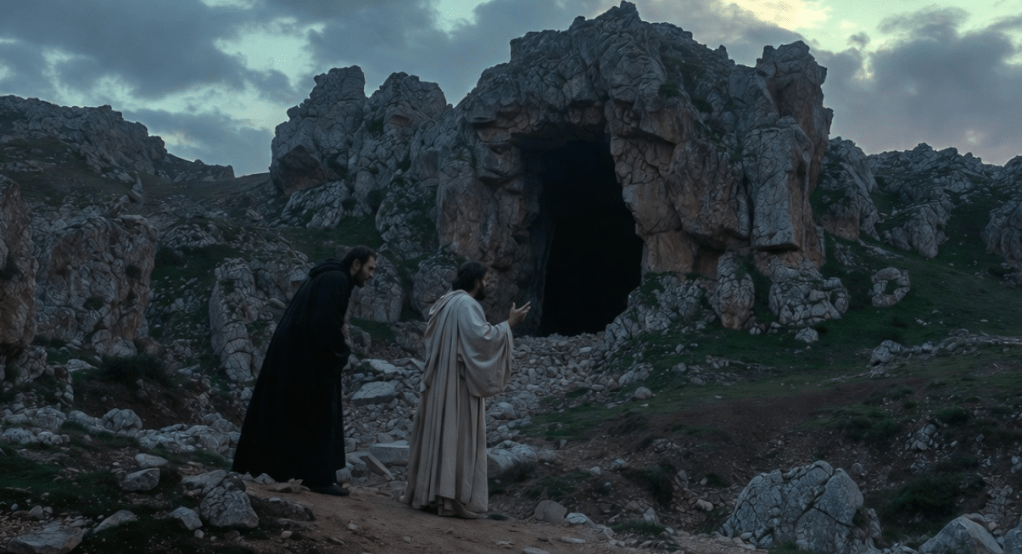

Perhaps metaphysics can assist us where mathematics cannot. In the opening canto of Dante’s Purgatorio, Dante and Virgil have just emerged, streaked with soot and dust, from the terrible circles of Hell. They encounter a figure from classical antiquity, Cato the Younger, posted at the base of the mountain as a kind of watchman—Purgatory in Dante is represented as a mountain with an apex, the opposite shape of Hell’s inverted cone. It is not clear—to me at least—why Dante chose Cato the Younger as Purgatory’s gatekeeper. He seems singularly unsuited for the job: he committed suicide, and he was a violent opponent of Caesar. At the end of the Inferno, Dante places Brutus and Cassius, the conspirators against Caesar, in the gnashing mouths of Satan himself. But let us leave this apparent inconsistency aside, and resume our topic.

Virgil prepares Dante for the ascent up mount Purgatory by washing his face and wrapping a “rush” (reed) around his waist. Scholars tell us that the reed, with its flexibility and strength, was a medieval symbol for humility and abstemiousness, virtues which are required for passage through Purgatory. When Virgil plucks a reed from the ground, Dante notices that the plant instantly regenerates itself. In Longfellow’s translation, the lines are:

There he begirt me as the other pleased;

O marvelous! For even as he culled

The humble plant, such it sprang up again.

[Purg. I.133-135]

Commentators on the Divine Comedy have interpreted this scene as laden with symbolism: whereas the resources of the material world are finite and fixed, the spiritual resources of the divine realm are self-renewing and inexhaustible. Love and wisdom, for example, are not zero-sum resources. If I give love or wisdom to someone else, I am not thereby depleted. On the contrary: I may in fact gain something myself. Suppose I have knowledge of some subject, and wish to teach it to another.

My teaching—my giving of wisdom to another, such as it is—does not diminish my own knowledge. In fact I probably gain in knowledge myself, through the very act of teaching. The same could be said for love. It is a self-renewing resource: if I love someone, and I share my love, I am not thereby diminished in my “volume” of love. So not everything is a zero-sum game. A gain for one is not inevitably a loss for another. Perhaps both parties can win.

And this, I think, is what Dante is trying to tell us in the opening canto of the Purgatorio. If we cease to think in terms of worldly goods and the imperative of our own immediate gratification, a whole new perspective opens up for us. We must not assume that another’s gain always is our loss. The zero sum game is a spiritual trap for the unwary soul. Dante wants us to understand that when we gird ourselves with the “reeds” of humility and moderation, we will be able to perceive the world in expansive and noble ways that have nothing to do with zero sum games. This lesson, drawn from Dante’s spiritual domain, can assist us in learning to work with others in ways that promote cooperation, shared interests, and mutual understanding. Conflict is not always inevitable; but by assuming that it is inevitable, man helps make it so.

.

.

Read more in the new, annotated translation of Cicero’s On The Nature Of The Gods.