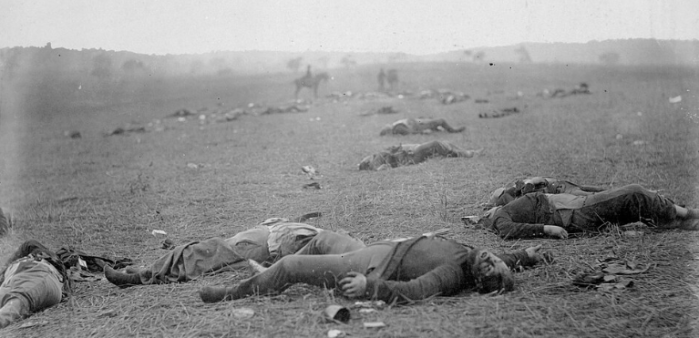

The two greatest artistic productions to come out of the American Civil War were Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch-Book of the War, and Herman Melville’s poetic masterpiece, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War.

Gardner’s work we discussed in 2014 in Thirty-Seven. Melville’s haunting collection of poems needs some introduction, for the work is almost entirely unknown outside the halls of scattered collegiate English departments and the bookshelves of Melville devotees. Why is it that the author of Moby-Dick, a man whose probing intensity plumbed the depths of the earth’s watery foundations, has been so neglected as a versifier? The answers, I suspect, have something to do both with him and with us. Poetry has never been an immensely popular literary form, even in Melville’s day. One would think that it should be: it is compact, laden with imagery and enticing turns of phrase, and often easy to commit to memory. But perhaps it makes demands on readers that most are unwilling to bear. Its unfamiliar grammatical constructions and often elusive meanings do not accord well with the short attention spans of our modern era. This is a shame, but it does not mean that we should cease to recognize and praise what is noble and stately in verse.

A common perception of Melville is that he was detached and aloof from the political events of his day. He has been unfairly depicted as perched atop a metaphorical masthead, surveying the damage below from the security of his nest. As his biographers will tell us, however, this portrayal is far from accurate. It is true that he did not actively participate in politics, and did not make public pronouncements about the Civil War as it raged; but this does not mean he was uninterested in, or unaffected by, the conflagration that engulfed his country from 1861 to 1865. During the conflict he frequently visited his cousin Henry Gansevoort, a Union officer, even becoming involved in a short pursuit of the Confederate guerilla leader John Mosby; he met General Ulysses Grant in Virginia in 1864; and he followed the progress of the war meticulously in the newspapers.

After years of frustrating failure, Melville finally abandoned the novel in the late 1850s as a vehicle of his artistic expression. Thereafter he would publish only in poetry, and even then on a very small scale. By the late 1860s he was remembered, if at all, as a romantic travel writer from the days of sail, whom time had inexorably passed by and left in obscurity. But Melville was not yet done with the world. He still had much to say, and had found a new mode of expression. By this time he had abandoned the old dreams of commercial success; in a way, this was a liberating experience, since it allowed him to do what he pleased without fretting about the acceptance of the public, of whom bitter experience had taught him to be wary.

Battle-Pieces was published in 1866. It is likely that Melville had worked on it intermittently during the war, and gave it final form and polish after the surrender at Appomattox provided him with a definite ending-date for the conflict. Its seventy-two chronologically arranged poems each feature a particular event or “aspect,” of the war; the unifying themes of the work revolve around the war’s tragic fratricidal nature, its occasional moral ambiguity, and the need for a new, postwar conception of the United States. The general tone is somber and reflective; there is no celebratory flag-waving, no insensate jingoism, no bugles and bombast, no sharp divide drawn between heroes and villains.

For Melville, as for Abraham Lincoln, the war was both a crucible and an atonement: a crucible in the sense that the United States would never be able to realize fully the dreams of its founders without undergoing a fiery rebirth; and an atonement in that the entire nation would have to pay a price for generations of injustice and oppression in the form of chattel slavery. Melville was a staunch Union man, but his personality recoiled from the extremism and vindictiveness of abolitionists like Emerson or Thaddeus Stevens. He came from a Democratic family, and like many of his peers was slow to appreciate Lincoln’s greatness. Some of his views are not widely shared by historians today; he seemed, for example, to hold Union Gen. George McClellan’s military abilities in undeservedly high regard.

Yet Melville saw nuances where others saw sharp tones; for him, the shame of slavery should be shouldered as much by the North as by the South, since all regions of the country had profited from it in one way or another. What mattered to him was binding up the country’s wounds, promoting a reconstruction regime that did not humiliate or embitter former enemies, and achieving a degree of salutary understanding that could form the basis of a new and just society.

It is interesting that no other writer attempted to do what Melville did in Battle-Pieces. I believe he aimed at nothing less than a kind of American Aeneid: that is, a heroic testament in verse to the birth, or rebirth, of a nation destined to play a decisive role in world affairs. His peers were not up to the task, or never attempted to conceive the task. Longfellow lacked the heroic vision; Emily Dickinson was a recluse who could not be pried out of her boudoir; and Emerson was too narrowly a New England partisan. Even Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps falls far short when compared to Battle-Pieces: its abstractness removes it from the distinctly American context of the war, and its sprawling, rambling verses seem ill-suited to the seriousness of the subject matter. Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage, while a great novel, remains a deeply personal tale, and one restricted in scope by its somewhat facile and immature conception of war. Nathaniel Hawthorne had died in 1864, but even had he been alive, he was not the type of writer who could deal with contemporary themes.

Melville’s economy of poetic management is wondrous. In “Shiloh: A Requiem,” for example, he expresses in simple lines an indelible image of this terrible engagement:

Skimming lightly, wheeling still,

The swallows fly low

Over the field in clouded days,

The forest-field of Shiloh—

Over the field where April rain

Solaced the parched ones stretched in pain

Through the pause of night

That followed the Sunday fight

Around the church of Shiloh—

The church so lone, the log-built one,

That echoed to many a parting groan

And natural prayer

Of dying foemen mingled there—

Foemen at morn, but friends at eve—

Fame or country least their care:

(What like a bullet can undeceive!)

But now they lie low,

While over them the swallows skim,

And all is hushed at Shiloh.

As in any great work there is some unevenness of quality. Some of the poems do not quite reach their intended marks. “Lyon: Battle of Springfield, Missouri” is one unfortunate example. But we cannot expect perfection in any product of human artistry. What matters is the greatness of Melville’s vision, the all-embracing attempt to give the war a larger significance, and the inherent decentness of the author’s character. Melville felt compelled to add a “Supplement” essay at the end of his book, in which he describes some of his personal sentiments in prose. It is a revealing insight into the mind of an intensely private writer who rarely, if ever, spoke directly about political questions. The tone of the Supplement is infused with pleas for reconciliation, forgiveness, and brotherhood:

There seems to be no reason why patriotism and narrowness should go together, or why intellectual impartiality should be confounded with political trimming, or why serviceable truth should keep cloistered because not partisan. Yet the work of Reconstruction, if admitted to be feasible at all, demands little but common sense and Christian charity. Little but these? These are much…

Patriotism is not baseness, neither is it inhumanity. The mourners who this summer bear flowers to the mounds of the Virginian and Georgian dead are, in their domestic bereavement and proud affection, as sacred in the eye of Heaven as are those who go with similar offerings of tender grief and love into the cemeteries of our Northern martyrs. And yet, in one aspect, how needless to point the contrast.

Melville’s literary hopes for Battle-Pieces were as surely dashed by an apathetic literary market-place, as his aspirations for Reconstruction were wrecked on the rocks of political factionalism, narrow-mindedness, and internecine hatred. The book sold poorly; it was understood by few, and appreciated by even fewer. But altogether and in retrospect it is a stunning literary achievement, grand in conception and elegant in composition.

Reconstruction similarly dismayed Melville. With the removal from the political scene of its one irreplaceable stabilizing and unifying figure, Abraham Lincoln, the nation descended in 1865 into a form of polarized inertia that forever squandered the opportunities presented by Reconstruction. Radicals in Congress clashed with an inept president and a resentful South; the massive federal investment and commitment which should have accompanied Reconstruction never occurred; and political wisdom gave way, on both sides, to stridulous fanaticism. It is a lesson that remains timely. Melville’s Battle-Pieces stands as a monument to our darkest years because it succeeded, in a way that no other literary work succeeded, in distilling a meaning from the conflict derived from the values of martial virtue, heroism, compassion for the fallen, brotherhood, and the indissoluble bonds of our shared history.

.

.

[I recommend the edition of Battle-Pieces published by DeCapo Press in 1995, with an introduction by Lee R. Brown. It is a sturdy, well-printed facsimile of the original 1866 edition.]