The two greatest artistic productions to come out of the American Civil War were Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch-Book of the War, and Herman Melville’s poetic masterpiece, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War.

Continue reading

The two greatest artistic productions to come out of the American Civil War were Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch-Book of the War, and Herman Melville’s poetic masterpiece, Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War.

Continue reading

In November of 43 B.C., Rome was gripped by a terrible sense of foreboding. The historian Appian, in his Civil Wars (IV.1.4) relates that all kinds of strange portents were observed around the city. Statues sweated blood; a newborn infant uttered words; lightning struck sacred temples; and cattle spoke with a human voice. So alarmed were some senators that they summoned expert diviners from Etruria to weigh these ominous signs. The most authoritative of these was an elderly man who told them, “The monarchical rule of ancient times is returning. You will all be slaves except me.” Once the Etruscan priest spoke these words to the startled senators, says Appian, he closed his mouth and held his breath until he dropped dead before them.

Continue reading

Abraham Lincoln’s literary powers were a product of his life experiences and his innate abilities. From a young age, his exposure to tragedy had been personal and continuous. The death of his mother, the death of Ann Rutledge, and various other hardships had given him an acute sensitivity to the meaning of loss. In the writing of letters of consolation, Lincoln was able to harness these sentiments and express them in ways that gave specific tragedies a timeless and almost cosmic significance. We have already here discussed the famous Bixby Letter. Two other letters of consolation from Lincoln’s hand, much less well-known, merit our attention as models of compassion and heartfelt sympathy.

Continue reading

Ambrose Bierce remains the only major writer who actually experienced, and survived, combat in the American Civil War. Henry James and Mark Twain chose to sit out the war. Twain’s actions in particular look very much like the behavior of a deserter. Walt Whitman served as a nurse, but he did not fight.

Continue reading

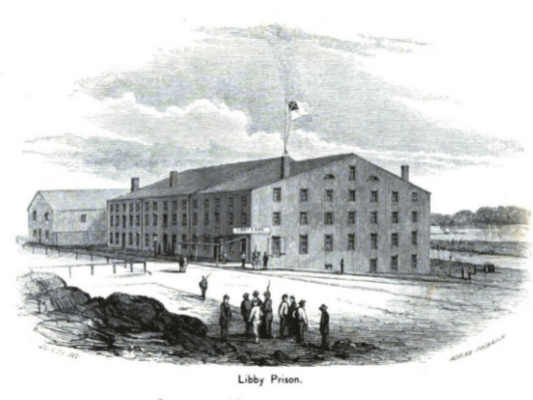

The greatest prison camp escape in American history took place at Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, in February 1864. On a cold winter night, 109 Union officers crawled through a suffocating, claustrophobic tunnel from a Confederate hell-hole to an empty lot near the building, and from there tried to make their way through hostile country to Union lines more than fifty miles away. Many of them won their freedom, but many were recaptured and sent right back to prison.

Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.