The name Heinrich Barth is almost unknown today. But he is without doubt the greatest explorer that Germany produced in the nineteenth century, and probably even in the twentieth. Not only did he penetrate completely unknown regions of Africa, but he kept a meticulous record of his travels, to such an extent that his published works are still useful to scholars today. Even in his own day he did not receive the recognition that he deserved; central Africa was then so unknown even to educated Europeans that a balanced appraisal of his work was not possible at the time. Yet a review of his life and travels leaves little doubt that he must be ranked among the bravest and most resourceful of all explorers of the African continent.

He was born in Hamburg in 1821. His father was a merchant and trader, and possibly imparted a love for travel and foreign languages in his son. The young Heinrich distinguished himself in his early schooling by showing a passion for hardship and foreign lands: as a teenager he had already begun to teach himself Arabic, and to master his body with a rigorous physical fitness regimen. Enrolling in the University of Berlin in 1839, he basked in the aura of Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Ritter, and August Boeckh, brilliant instructors in the fields of geography, biology, and philology. By this time he had also mastered Latin, and became well acquainted with classical literature; a trip to Italy further reinforced these classical inclinations. We get a taste of his Stoic character when, in May 1842, a massive fire in Hamburg severely damaged his father’s business, and also totally destroyed Heinrich Barth’s personal library (which was extensive even as a student). His comment on this tragedy, worthy of Simonides, was this:

One’s only secure possessions are those which he carries within him. Wealth? Can be gone in a second. Outward joy? Breaks as easily as glass. But inner strength and refinement can never be taken away–they only disappear when one ceases to exist, making them superfluous.

He received his university degree in 1844, after completing a dissertation on the commercial activity of the ancient Greek city of Corinth. He had no job prospects; yet he audaciously proposed to undertake an extended journey around the Mediterranean’s shores. He believed that the resulting book from such a trip would attract the attention of professionals. He had no money, but his father generously agreed to finance Heinrich himself: on top of everything else, he was blessed with supportive and broad-minded parents. Before setting out for the trip, he spent some time in London perfecting his mastery of spoken and written Arabic, which he knew would be an essential tool. From 1845 to 1847 he traversed North Africa, then moved up through the Levant into Syria and Turkey, finally ending in Greece. There was some element of risk involved: he had been robbed by bandits near Egypt. He published a book about these experiences in 1849.

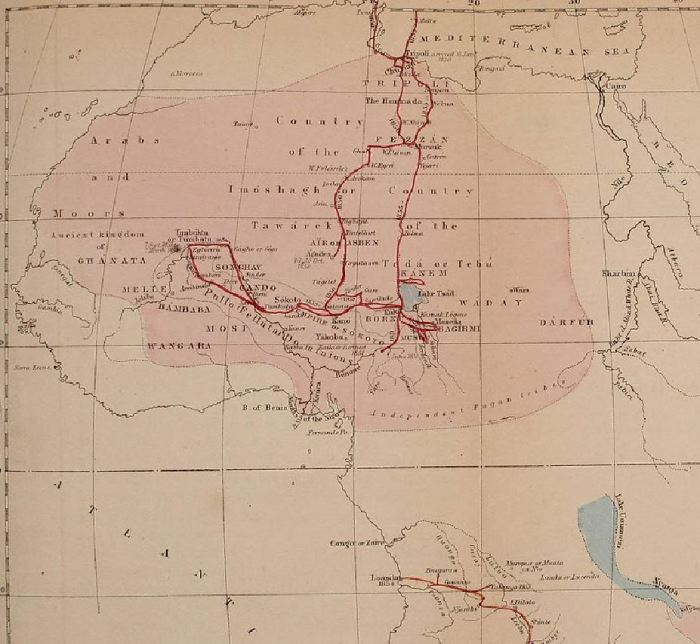

This trip would set the stage for what would prove to be the pivotal experience of his life. We must first keep in mind that the African continent in the 1840s was largely terra incognita to Europe; indeed, the source of the Nile was not even known until the late 1850s. Explorers who proposed to penetrate beyond the Sahara into the heart of the continent would have been viewed in the same way as astronauts are today. A British explorer named James Richardson had received a commission from his government to conduct an expedition into central Africa; he needed men of proven worth and experience, and Barth offered his services. He was accepted; besides all the other languages he knew, he was also fluent in English.

He freely acknowledged the debt he owed to those who came before him. In his monumental five-volume record of his expedition, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, he would write nobly:

In matters of science and humanity all nations ought to be united by one common interest, each contributing its share in proportion to its own peculiar disposition and calling. If I have been able to achieve something in geographical discovery, it is difficult to say how much of it is due to English, how much to German influence; for science is built up of the materials collected by almost every nation, and, beyond all doubt, in geographical enterprise in general none has done more than the English, while, in Central Africa in particular, very little has been achieved by any but English travelers.

Let it not, therefore, be attributed to an undue feeling of nationality if I correct any error of those who preceded me. It would be unpardonable if a traveler failed to penetrate further, or to obtain a clearer insight into the customs and the polity of the nations visited by him, or if he were unable to delineate the country with greater accuracy and precision than those who went before him.

For the journey he would call himself “Abd al-Karim Barth al-Inglisi.” It was not, of course, a good idea to appear too conspicuously foreign. Among his many notebooks, he wrote the following epigraph in Arabic, perhaps as inspiration for the road ahead:

Knowledge is power.

Because science is

The confidante in the wilderness,

The companion in a foreign land,

The storyteller in solitude,

The guide in joy and sorrow,

The weapon against the enemy,

And the ornament for friends.

The expedition left France and arrived on the North African coast. In 1850 Barth and his comrades crossed the Sahara (an extremely arduous feat in that era), and arrived in the city of Agadez in what is today Niger. But the years 1851 and 1852 would bring disaster, as the deaths of the two other principals of the expedition, Richardson and Adolf Overweg, left Barth on his own. But in some strange way, this may have been exactly what Barth’s life up to this point had led to: for years, he had cultivated his self-sufficiency and independence. He was by now an experienced traveler, able to record everything that mattered about a region: language, climate, biology, topography, and ethnic details.

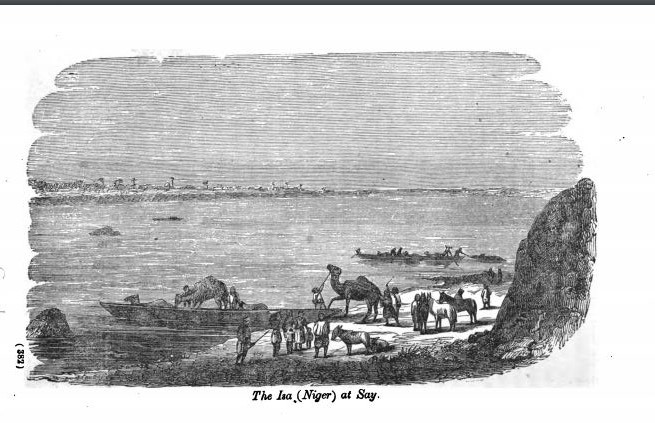

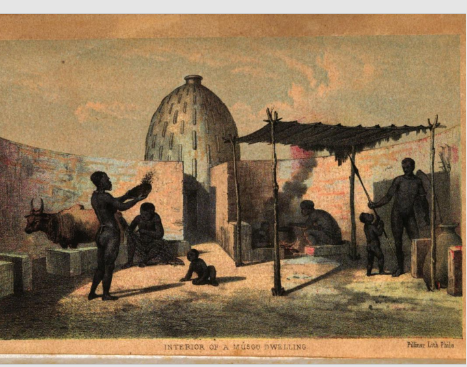

From this point Barth was on his own. He logged about 12,000 miles of travel in what is now Cameroon, Chad, and Timbuktu, patiently recording every observation that mattered. His fluency in Arabic was put to good use, as that language was (and is) the lingua franca of the Islamic world; yet during his time in central Africa he also managed to learn several regional tongues, specifically Hausa, Fulani, and Kanuri. Curiosity about travelers goes both ways; not only was he interested in the customs of the diverse peoples he encountered in Africa, but the same peoples were of course intensely interested in him. Who was this tall, pale-faced stranger with his baggage trains, books, and strange scientific and medical instruments? Barth records the following amusing anecdote, which shows that humor and curiosity are universal:

The princesses also, or the daughters of the absent king, who in this country too bear the title of “mairam” or “méram,” called upon me occasionally, under the pretext of wanting some medicines. Among others, there came one day a buxom young maiden, of very graceful but rather coquettish demeanor, accompanied by an elder sister, of graver manners and fuller proportions, and complained to me that she was suffering from a sore in her eyes, begging me to see what it was ; but when, upon approaching her very gravely, and inspecting her eyes rather attentively without being able to discover the least defect, I told her that all was right, and that her eyes were sound and beautiful, she burst out into a roar of laughter, and repeated, in a coquettish and flippant manner, “beautiful eyes, beautiful eyes.” [p. 297]

Finally, on August 28, 1855, after an absence of five years and five months, Heinrich Barth returned to Tripoli in North Africa. He had been gone so long that London assumed he had perished. In Hamburg, German officials awarded him a gold medal. Tragically, however, his achievements became obscured in a swell of professional jealousies, conflicting national prides between England and Germany, and simply bad timing. Frustrated with the lack of recognition for his achievements, he applied himself to write his testament to posterity, the 3,500 page Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa. (Mercifully, an abridged one-volume version was also prepared, from which the quotes in this article are taken). Barth strikes a note of pride in his discoveries:

Thus I closed my long and exhausting career as an African explorer, of which this narrative endeavors to incorporate the result. Having previously gained a good deal of experience of African travelling during an extensive journey through Barbary, I had embarked on this undertaking as a volunteer, under the most unfavorable circumstances for myself. The scale and the means of the mission seemed to be extremely limited, and it was only in consequence of the success which accompanied our proceedings that a wider extent was given to the range and objects of the expedition; and after its original leader had succumbed in his arduous task, instead of giving way to despair, I had continued in my career amid great embarrassment, carrying on the explorations of extensive regions almost without any means.

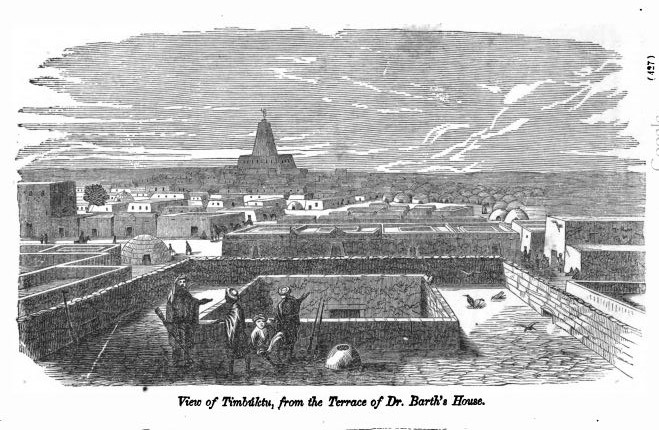

And when the leadership of the mission, in consequence of the confidence of her majesty’s government, was entrusted to me, and I had been deprived of the only European companion who remained with me, I resolved upon undertaking, with a very limited supply of means, a journey to the far west, in order to endeavor to reach Timbúktu, and to explore that part of the Niger which, through the untimely fate of Mungo Park, had remained unknown to the scientific world. [p. 537]

He was eventually awarded a post at the University of Berlin. He continued to travel, visiting the Balkans extensively in 1865. In November of that year he died suddenly, possibly the result of an intestinal disease he had contracted in Africa. Barth’s biographer, Steven Kemper, speculates in his book A Labyrinth of Kingdoms that the cause of death was the result of years of hard living and poor diet while on the march. An autopsy also revealed a bullet lodged in his thigh, a relic from an encounter with bandits. He was only forty-four years old. But his achievements and his books live on, and they assure him immortality.

Read more on the exploits of visionary men in Pantheon:

You must be logged in to post a comment.