Tales of superlative leadership abound in naval history. Through the study of historical examples, we are instructed in the qualities and characteristics of proper command. In early 1871 the British Admiralty sent a detachment of soldiers and marines to Australia aboard the iron screw frigate Megaera. The ship carried 42 officers, 44 marines, 180 seamen, and 67 boys, for a total of 333. After stopping briefly at the Cape of Good Hope, the Megaera embarked on the long journey across the Indian Ocean to Sydney. It was anticipated that the vessel would reach its destination by July 5.

But Fortune would not be so accommodating. On June 8 the ship collided with a terrible storm, and became afflicted with a serious leak; with every passing hour, the water in the ship’s hold rose by one inch. The captain of the Megaera was Arthur T. Thrupp, an experienced Royal Navy commander and a veteran of the Crimean War. Captain Thrupp ordered the pumps to be manned throughout the night, and by morning the level of water in the engine room had been reduced to thirteen inches. But the problem persisted, because the location of the leak could not be found; not only was the bottom of the hold submerged, but the inside of the hull was lined with iron plate and cement. Since the leak could not be located and plugged, the only available remedy was continuous pumping. Soon these unrelieved exertions began to take their toll on the crew.

Day after day, the pumps were manned. The captain even had water hauled out from the hold in buckets; fife and drum music was deployed to raise the men’s morale and help synchronize their tedious labors. But by June 13, it was clear that the Megaera was losing its battle against the rising water level. The hole was eventually discovered; it was a worn-out section of iron plating. A team of men attempted to seal the hole with another piece of plate covered with gutta-percha (a latex obtained from a certain species of tree), but they lacked the proper tools for the task. Fortunately, the ship was by this time (June 17) about ten miles from St. Paul Island, a tiny speck of land in the Indian Ocean. The island is barely two miles in length and one in width.

When the ship finally put ashore at St. Paul Island, Captain Thrupp sent a diver to inspect the bottom of the ship’s hull. The diver discovered that the hull was infested with rotted timbers and thin, worn plating; the vessel was essentially unseaworthy and should never have passed inspection before leaving England. Captain Thrupp, therefore, did the only sensible thing under the circumstances: he ordered the men to make camp on the island, remove the supplies from the ship, and await rescue. Fortunately the island was inhabited by two Frenchmen, who were able to show the crew where to find water.

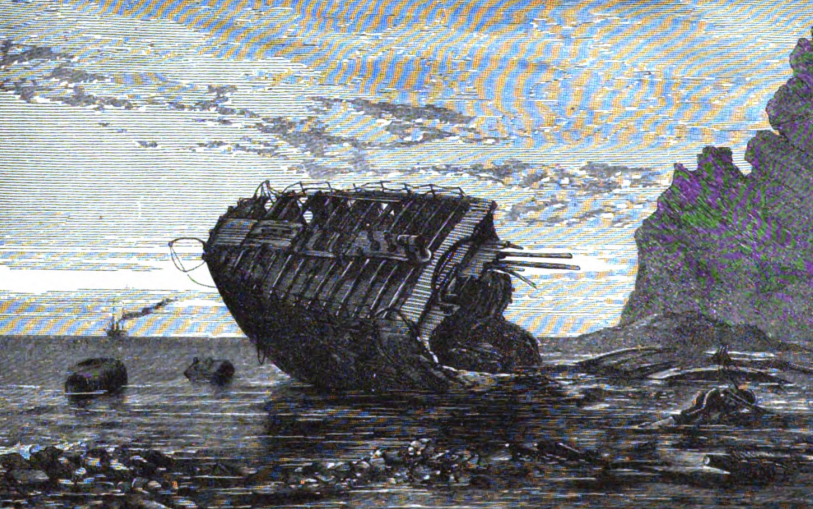

Thrupp ordered all hands to begin unloading the ship’s cargo to shore. The Megaera was now so unseaworthy that the decision was made to run her aground. Day after day under the burning sun, the men labored to salvage what could be saved from the wreck of the ship. Captain Thrupp, like many commanders of expeditions stranded in remote parts of the globe, realized that unless he maintained the strictest discipline, morale among his men would rapidly deteriorate. He ordered an insubordinate seaman who had refused to work to be lashed with a cat-o’-nine-tails; this spectacle quickly deterred any other potential shirkers.

The ship finally broke apart in a heavy storm. Rescue was now the only hope for the stranded men. Captain Thrupp maintained a strict routine for his men: he appointed sanitary inspectors, set up a signal station, formed an executive staff, and even had guards posted. One the island’s highest point, they erected a pole with the British ensign hanging upside down, to signal distress to any passing ship that might see it. On July 16, the flag was spotted by a passing Dutch ship, the Aurora; an officer of the Megaera, Lt. Lewis Jones, boarded the Aurora, which eventually landed in Java in early August. From there, Lewis telegrammed the British legation in Hong Kong, informing it of the condition of the Megaera’s stranded crew on St. Paul Island. Rescue was now just a matter of time.

The challenge facing Captain Thrupp was how to make his meager provisions last until the arrival of a rescue party. From the ship they had rescued about 13,000 pounds of biscuit, and six weeks’ worth of other foodstuffs, mainly flour, preserved meats, tea, rum, chocolate, and some sugar. The men could not be certain when a rescue ship would arrive—it might take much longer than expected. To slow the rate of food consumption, Thrupp ordered the men placed on one-third rations. This caloric intake was fortunately supplemented by fresh fish and the meat of wild goats, which were present on the island.

Some of the men did suffer from tropical diseases, but not many. Morale remained high due to Strupp’s insistence on a daily regimen to keep the men working and constantly busy. But salvation was near. A steamer, the Malacca, left Hong Kong with orders to rescue the castaways on St. Paul Island and transport them to Sydney. The Malacca reached the island on August 29, rescued the Megaera survivors, and departed for Sydney. En route to Australia, Captain Thrupp was transferred to a different ship bound for England, where he would have to face an obligatory inquest over the loss of the Megaera. He was not only completely exonerated, but in fact was commended for his leadership under severe duress. His persevering leadership had saved the lives of all, or at any length most, of the men under his responsibility.

.

.

Read more on the qualities of good command in the new annotated and illustrated translation of Cornelius Nepos’s Lives of the Great Commanders:

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.