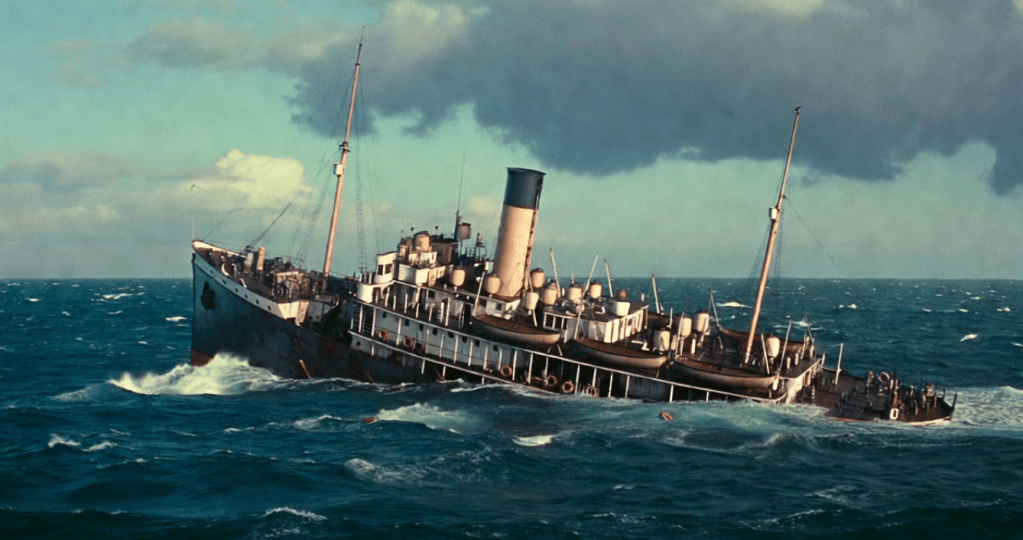

It is at moments of unremitting extremity that we discover our true natures. The tragic loss of the British ship Stella in 1899 provides an illustration of this principle. The story appears in a 1962 volume of nautical lore entitled Women of the Sea by the maritime writer Edward R. Snow; but since the book has long been out of print, it will be retold here in abbreviated form, with Mr. Snow’s account as my primary source.

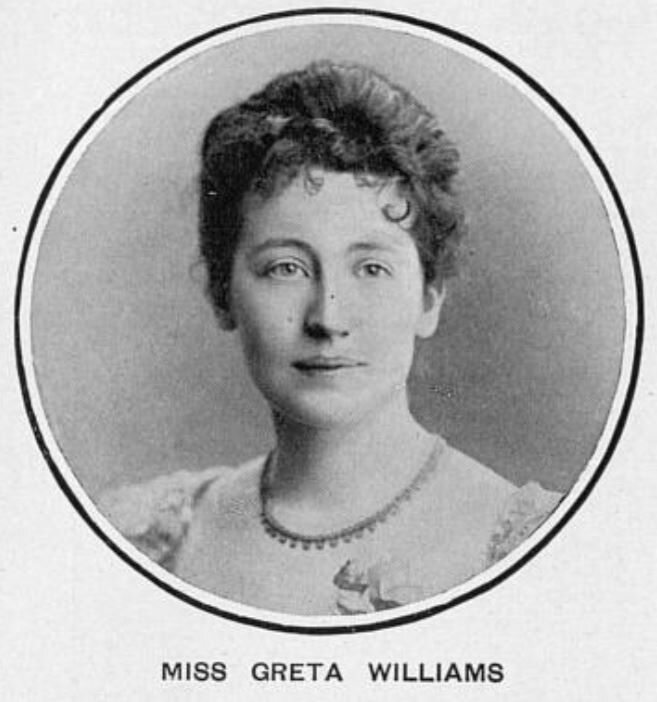

The twin-screw passenger steamship Stella left Southampton, England for Guernsey in the Channel Islands on March 30, 1899. The ship carried 140 passengers, and had a crew of forty. She was captained by one William Reeks. The vessel’s tonnage was just barely over 1,000, and had a length of 253 feet. We are fortunate to have a vivid first-hand account of the events that followed, because one of the passengers, a resolute woman named Greta Williams, survived the ordeal. Williams was an opera singer, a celebrated soprano who had already won several prestigious awards before 1899. After leaving England, the Stella made good time, and cut through the water briskly despite the ominous presence of a thick fog. After about five hours at sea, the ship made its rendezvous with Fate. Williams describes what occurred:

Nearly five hours had passed since we sailed, and we were still going smoothly ahead. Suddenly, without the slightest warning, there came a strange, grinding sound and a shock, which even the merest landsman knew was not caused by the sea. The check to our easy running, the sudden cries we heard, the hurrying of feet, and many dismaying noises told us that something terrible had happened.

Indeed something terrible had happened, for the Stella had collided with “Black Rock,” one of a notorious group of rocks known as the Casquetes. These treacherous projections were located about eight miles west of Alderney Rocks, and had long been a bane to mariners. For some reason, the Stella‘s captain had not reduced his speed in the fog, so that when the ship struck the rocks, the damage was so extensive that the ship was effectively doomed. The order was given to lower the lifeboats at once, but the Stella was already sinking quickly. Fortunately, neither the passengers nor the crew panicked, but displayed the kind of discipline and cool-headedness for which British vessels were justifiably recognized.

Women and children were, of course, given first seating. Unfortunately, there were only seven lifeboats. When Ms. Williams saw how overcrowded one was, she and her sister Theresa decided to use another; this decision saved their lives, for the lifeboat was pulled down by the vortex created when the Stella plunged into the depths. It took only eight minutes—eight minutes!—for the Stella to recede below the waves. Williams reflected later on the shocking suddenness of Fate’s reversals:

Seven short minutes only had passed since we were lying in our cozy stateroom in a strong and beautiful steamer—and now she had vanished, and we were tossing wildly on the seething waters which had just engulfed her…The air was burdened with the most dreadful sounds—the cries of the drowning and despairing, and the infinitely worse appeals of those who begged to be taken into boats that were already overladen…They fought despairingly to get into our little craft—clinging to the gunwale and clutching wildly at those of us whom they could reach. One of the men in our boat beat them off with his oar, and they fell back into the water and took their chance again.

Perhaps it is a lesson we should all pause to consider: that heaven and hell can change places very quickly. I cannot fail to repeat an incredible instance of courage and self-sacrifice recorded in Ms. Williams’s account. After the ship went down, and many men and women bobbed helplessly in the waves, a stewardess named Mary Ann Rogers swam to one of the lifeboats. She was urged to climb into one of them, but, after inspecting their condition, she said stoically, “No, they are too full already. There is no room for me.” She was implored to get in, but she persisted in her refusal, not wishing to endanger those already in the lifeboats. Mrs. Rogers slowly drifted away from the boats and, when she was still within earshot, she raised her hands to the sky, and cried out, “Lord, have me!” Those were her last words; she then disappeared beneath the water. The doleful scene was one Greta Williams would never forget; she later called Mrs. Rogers “surely one of the noblest women who ever gave their lives for others.”

Five hours after the sinking of the Stella, the survivors in the lifeboats were shivering, exhausted, and terrified. Suddenly Williams had the idea that singing to the survivors might be a way to raise morale. With a bit of encouragement from her sister, she began; and, although some survivors were hardly in the mood to listen to singing, the consensus was that she performed a valuable service during those terrible hours. By taking the survivors’ minds off their suffering, Williams helped sustain their spirits until deliverance finally arrived. On the morning of March 31, Williams’s boat was rescued by the ship Vera, which delivered them to St. Helier in Jersey. The total loss of life was heavy: out of 140 passengers and 40 crewmen, 86 passengers and 19 crewmen perished.

The inquiry into the tragedy determined that Captain William Reeks, with his insistence on steaming at a reckless speed, bore full responsibility. Greta Williams died in 1964 at the age of 95.

You must be logged in to post a comment.