The Roman historian Sallust, in his Conspiracy of Catiline, reminds us that

Continue reading

It is tempting to believe that our current social problems are uniquely modern, and that they have no analogues to conditions of previous ages. A review of the thoughtful writings of the past shows that this belief is far from the truth. Consider, for example, this comment from the Latin dialogue Antonius, which was composed by the humanist Giovanni Pontano around 1487 and first printed in 1491:

Continue reading

In the 1340s the Italian scholar Petrarch composed a long letter to the poet Homer. He enjoyed these imaginary exercises in which he could “communicate” with some of the great literary figures of the past; there exist letters to Cicero, Livy, and some other ancient writers.

Continue reading

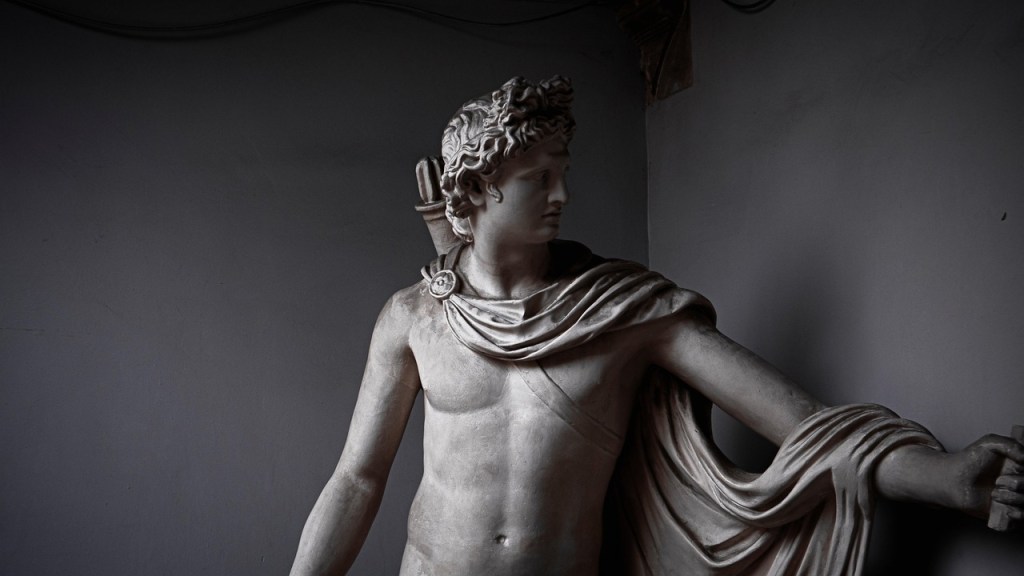

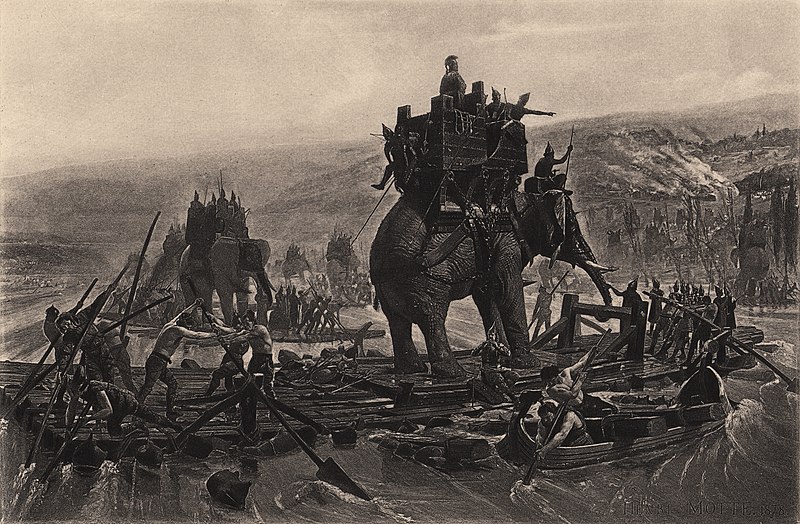

Alexander the Great’s incursions into the Indian subcontinent brought him into conflict with local rulers unwilling to submit to Macedonian rule. One of these rulers is known to history by the name Porus. The sources are vague and contradictory, but he apparently controlled the Punjabi region bordered by the Jhelum and Chenab rivers.

Continue reading

This morning my friend Dr. Michael Fontaine sent me an email that contained the following quote by the French Enlightenment thinker Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle. When Fontenelle, at the age of 85, met Rousseau in 1742, he counseled him, “You must courageously offer your brow to laurel wreaths, and your nose to blows.”

Continue reading

Philo of Alexandria wrote a relatively obscure essay entitled On the Prayers And Curses Uttered by Noah When He Became Sober. His translator has fortunately shortened this unwieldy title to the compact De Sobrietate, or On Sobriety. It contains the following passage of importance:

Continue reading

There is an interesting passage in the writings of Valerius Maximus (III.3) that is open to different interpretations. It reads as follows:

The Athenian statesman and lawgiver Solon is said to have enacted an unusual law in 594 B.C. The essence of the law was that, in times of civil conflict or crisis, every citizen had to take one side or another. Neutrality was not an option; one could not “sit on the sidelines” and wait things out. Anyone doing so would run the risk of being declared an outlaw (atimos), and might have his property confiscated.

The world is a much smaller place than we are aware. Things we do, actions we take, can have far-reaching effects that come back to us in ways we can never imagine. While events, places, and the flowing rush of time are shifting and transitory, the power of virtue is such that it transcends time and place. I was reminded of this recently after reading the Second World War memoirs of Col. Hans von Luck, a German commander who fought in all the major theaters of the European war.

Philo of Alexandria, in his essay on agriculture (De Agricultura), points out that there is a difference between an ordinary tiller of the ground, and an actual farmer; and that there is also a clear difference between a shepherd and someone who just tends to sheep. In the same way, he tells us, there is a great difference between a rider of a horse and a true horseman.

You must be logged in to post a comment.