It has been clear for some time that neither the American political right, nor its counterpart on the left, has capably embraced the leadership challenges of twenty-first century modernity. Even a cursory survey of the political landscape reveals a dismal picture. On the right, we find the mouthpieces of corporatist and plutocratic reaction, mixed with an assortment of cranks, religious ideologues, demagogues, and rogues; while the left, which once represented the interests of the working classes, has been almost entirely overwhelmed by a venomous and destructive obsession with identity, race, and gender politics, which accomplishes nothing except to corrode the fraternal bonds essential for the maintenance of a healthy social order. The inevitable result of this acute polarity has been a debilitating paralysis. Congress can hardly accomplish anything except token and toothless half-measures, which succeed only in delaying problems, instead of solving them.

Is there an alternative to the present state of affairs? Is there a way to combine a robust, nationally-minded patriotism with a concern for social justice, progress, and development? The answer is yes. There once existed a force on the American political scene which may be called the progressive right. It was an ideology that combined conservative, patriotic values—with an emphasis on individual social responsibility, good citizenship, public service, a muscular foreign policy, and a strong military—with a concern for social justice that was manifested in vigorous anti-trust and anti-monopolist prosecutions, legislation on fair wages and working conditions, civil rights, public health and education, and environmental conservation. In many ways, the progressive right combined the best features of both the left and the right. And yet this kind of program seems almost unthinkable today, in a corrupt political mural dominated by money, corporate influence, and parochial interests.

The first modern figure who may be placed in the progressive right camp is arguably Otto von Bismarck. As chancellor of Germany from 1871 to 1890, he was a veritable bastion of visionary conservatism. He championed the importance of a strong military—a requirement necessitated by both tradition and his nation’s geography—as well as the need for social order. At the same time, however, he enacted a stunningly progressive series of measures that ensured the loyalty of the citizen to the state. The Health Insurance Bill of 1883, the Accident Insurance Bill of 1884, the Old Age and Disability Insurance Bill of 1889, the Worker’s Protection Act of 1891, and the Children’s Protection Act of 1903: all of these laws went far beyond anything done in America or England at the time. Cynics have attempted to taint Bismarck’s achievement by asserting that he advanced progressive legislation only as a political maneuver to take the wind out of the socialists’ sails. In this they are mistaken. Bismarck genuinely believed that the foundation of a strong nation could only be a satisfied, healthy, and secure population, and that a government’s responsibility was to see that this was accomplished.

In this respect, Bismarck resembled that icon of the American progressive right, Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was an unapologetic nationalist, a firm believer in American power and its destiny. But at the same time—and in stark contrast to his social peers and political contemporaries—he had a consuming belief in the need for fair play and social justice. He practically worshipped the military, and considered an interventionist foreign policy a right and a necessity; but he was never a narrow-minded jingoist. His advocacy of physical fitness was legendary; he would have loathed our modern squeamishness in making physical training mandatory in youth education. Roosevelt was a maverick, and one of the most brilliant firebrands the American political system has ever produced.

What animated TR was a passion for justice and fairness. He detested the monopolistic practices of the tycoons of his day, and pursued anti-trust enforcement with a ferocity that has never been equaled. His “Square Deal” legislation regulated the railroads (in some ways, the “internet” of its day), as well as the food and drug industry. His reputation for even-handedness helped to negotiate an end to the Coal Strike of 1902. He took action to protect the environment from the predations of corporate power by setting aside an incredible amount of land for national parks and preserves. He tended to favor tariffs as reasonable safeguards to prevent the American economy from being overwhelmed by cheap goods from foreign competitors.

Perhaps the most complete expression of his political philosophy may be found in his “New Nationalism” speech, delivered in Osawatomie, Kansas in 1910. It was the responsibility of government, Roosevelt argued, to look after the welfare of its citizenry; and to do this, it must have the power to legislate and regulate where needed. Big business, he knew, could only be restrained and kept honest by a powerful central government; courts alone were incapable of matching the power of concentrated capital. If corporate power was not observed closely, he declared, the inevitable result would be the exploitation of the citizenry, which in time would dissolve the social fabric. Below is an excerpt from Roosevelt’s speech which provides a flavor of the whole:

At many stages in the advance of humanity, this conflict between the men who possess more than they have earned and the men who have earned more than they possess is the central condition of progress. In our day it appears as the struggle of freemen to gain and hold the right of self-government as against the special interests, who twist the methods of free government into machinery for defeating the popular will. At every stage, and under all circumstances, the essence of the struggle is to equalize opportunity, destroy privilege, and give to the life and citizenship of every individual the highest possible value both to himself and to the commonwealth. That is nothing new…Practical equality of opportunity for all citizens, when we achieve it, will have two great results. First, every man will have a fair chance to make of himself all that in him lies; to reach the highest point to which his capacities, unassisted by special privilege of his own and unhampered by the special privilege of others, can carry him, and to get for himself and his family substantially what he has earned. Second, equality of opportunity means that the commonwealth will get from every citizen the highest service of which he is capable. No man who carries the burden of the special privileges of another can give to the commonwealth that service to which it is fairly entitled.

Roosevelt called for wide-ranging progressive reforms: national health care, social security insurance, minimum wage laws for women, eight-hour workdays, workmen’s compensation, and an inheritance tax. What political “conservative” today would dare advocate in such a way for the public good?

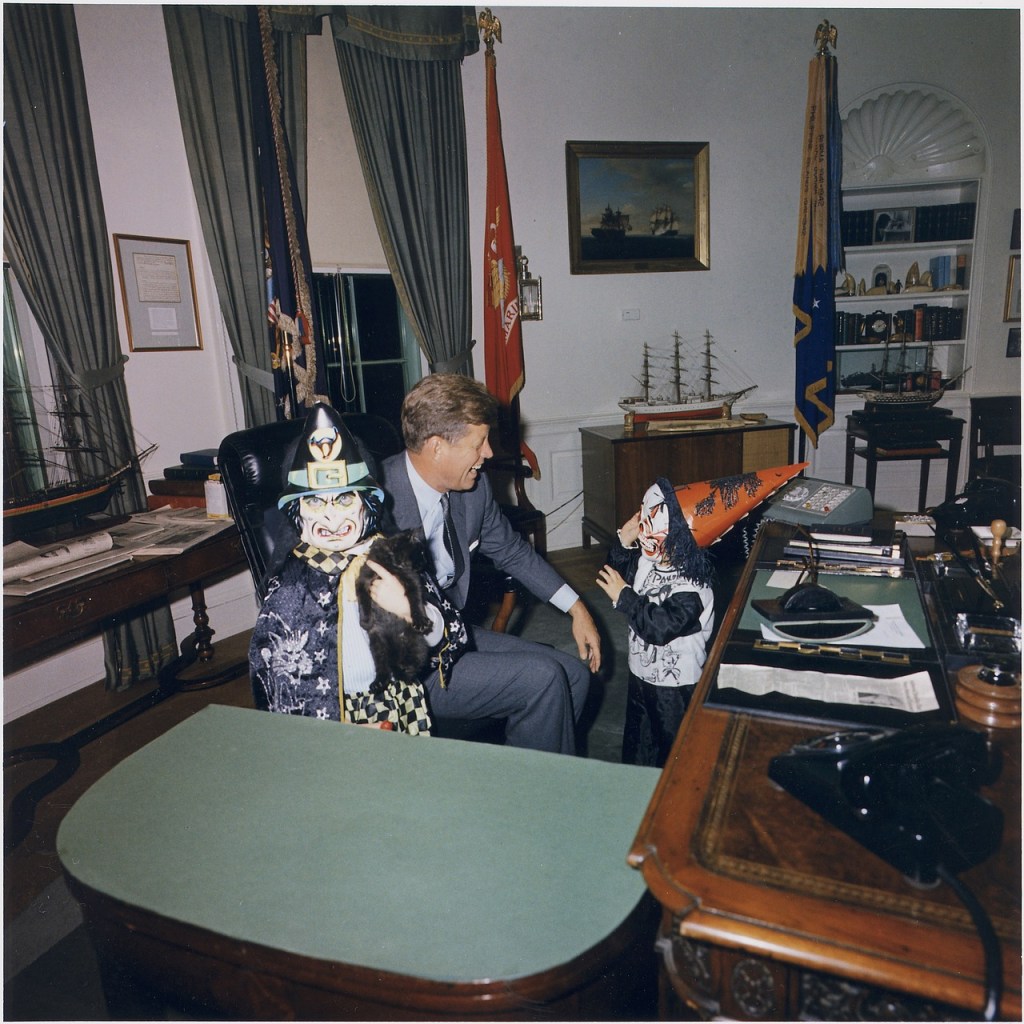

After Roosevelt, the progressive right faded. The reforms he instituted or advocated were either obstructed or ignored by his successors; his warnings against the pernicious influence of corporate control of government were maligned, derogated, or dismissed as outdated. I would argue that the last major figure of American progressive conservatism was John F. Kennedy. Although he was a Democrat, it is clear that by today’s standards, he must be considered a man of the right. Kennedy, like Theodore Roosevelt before him, was a combat veteran and understood the importance of a potent national defense. After taking office, Kennedy published an article in Sports Illustrated called “The Soft American,” and demanded a national program to cultivate youth fitness. He created a national office to address the issue; physical fitness, he argued, was the business of the federal government, and it deserved a comprehensive solution. JFK wanted the famously difficult “La Sierra” fitness program to spread across the country’s high schools. These kinds of initiatives would be unthinkable for a Democratic president today.

At the same time, Kennedy favored progressive legislation as a curative for social ills. He made civil rights a focus of his presidency, and pushed for an increase of the minimum wage. He was not afraid to denounce corporate power and control, which he saw as a potential threat to the public interest. One such instance was JFK’s denunciation of the steel trusts, which he delivered on April 11, 1962, after several steel corporations had colluded in price-fixing. Kennedy described it in this way:

Simultaneous and identical actions of United States Steel and other leading steel corporations, increasing steel prices by some 6 dollars a ton, constitute a wholly unjustifiable and irresponsible defiance of the public interest. In this serious hour in our nation’s history, when we are confronted with grave crises in Berlin and Southeast Asia, when we are devoting our energies to economic recovery and stability, when we are asking Reservists to leave their homes and families for months on end, and servicemen to risk their lives—and four were killed in the last two days in Vietnam—and asking union members to hold down their wage requests, at a time when restraint and sacrifice are being asked of every citizen, the American people will find it hard, as I do, to accept a situation in which a tiny handful of steel executives whose pursuit of private power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility can show such utter contempt for the interests of 185 million Americans. If this rise in the cost of steel is imitated by the rest of the industry, instead of rescinded, it would increase the cost of homes, autos, appliances, and most other items for every American family. It would increase the cost of machinery and tools to every American businessman and farmer. It would seriously handicap our efforts to prevent an inflationary spiral from eating up the pensions of our older citizens, and our new gains in purchasing power.

It is difficult to imagine any president today, Democrat or Republican, daring to speak this way on behalf of the public interest. Kennedy’s nationalist impulse also found expression in his declared goal of achieving a manned moon landing before the end of the 1960s. This was precisely the kind of grand, ambitious project that would have fired the imagination of Theodore Roosevelt, the architect of the Panama Canal project.

After JFK, the idea of a progressive right faded into near oblivion. “Conservatism” became a label for unchecked greed, and the worship of unrestrained corporate control over public, and increasingly private, life; overtly religious voices naively, or maliciously, claimed that the admonitions of faith could serve as a substitute for federal power in the regulation of plutocratic abuses; and a cruel apathy evidenced a contempt for social justice and the welfare of all citizens. “Liberalism,” in its turn, became a well-deserved term of derision for those who sought to elevate frivolity, irresponsibility, and self-indulgence to the status of a creed. Entirely vanished from the political scene was the concept of the public good—the idea that the needs of the whole should outweigh the needs of the few, or the one.

In 2024, for the first time in history, American billionaires now have a lower effective tax rate than the working class. Clearly both modern conservatism and liberalism have failed the American people. What is needed is a new form of progressive nationalism: a vigorous, strong leadership in the mold of Bismarck, Theodore Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy, a stewardship that weds patriotic nationalism with ambitious progressive programs. We need a restoration of national sentiment. We need to imbue our youth with a sense of responsibility to their nation; instead of looking at what the country can do for them, as President Kennedy said, they should look at what they can do for their country. We must restore the military draft, and the concept of public service. Plutocratic power must be brought to heel. Special interests must not be permitted to take precedence over the good of the American people. These things have been done before, as the preceding discussion has shown. And if we are to survive, they must be done again.

.

.

Read more about leadership, virtue, and service in the new translation of Cornelius Nepos’s Lives of the Great Commanders.