The island of Cerigo, modernly called Kythira, is situated off one of the southern-jutting fingers of the Greek peninsula. Greece’s rocky shores have without doubt claimed more than their fair share of shipwrecks; and in 1807, near the end of the Napoleonic wars, they became the scene of a terrible tale of maritime suffering and survival, which we will now relate.

In early January 1807, the H.M.S. Nautilus, commanded by Captain Edward Palmer, was selected to transport some critically important military dispatches from the eastern Mediterranean to Cadiz. On January 3, she embarked from the Bay of Abydos in the Hellespont, where she was part of the squadron of Sir Thomas Louis. The ship moved cautiously among the Greek islands, heading in a southern direction. Even for a skilled mariner, however, navigation in this region can be hazardous. Hidden shoals and rocks lurk nearly everywhere. Movement is even more difficult at night; and without the technological advantages of modern seamanship, any inexperienced ship captain in these parts courts disaster. A seaman named John Boone, a survivor of the wreck who published an account of his ordeal in 1827, explained:

About five o’clock in the evening we made the island [of Falconera], and shortly after, that of Anti-Milo, fourteen or sixteen miles N. W. of the extensive island of Milo, in lat. 36. deg. 41 min. N. long. 24 deg. 6 min. E. which we could not see, in consequence of the haziness of the weather: Here the pilot, a Greek, gave up his charge of the ship, being ignorant of the navigation beyond Milo. The care of the ship again devolved on our captain, who, anxious to obey orders so urgently given, and having so plainly seen Falconera and Anti-Milo, determined to go on during the night; and by passing between Candia and Cerigotto, he felt confident that by the morning we should be clear of the Archipelago, and have escaped the dangers of our passage. How weak are human foresight and experience!

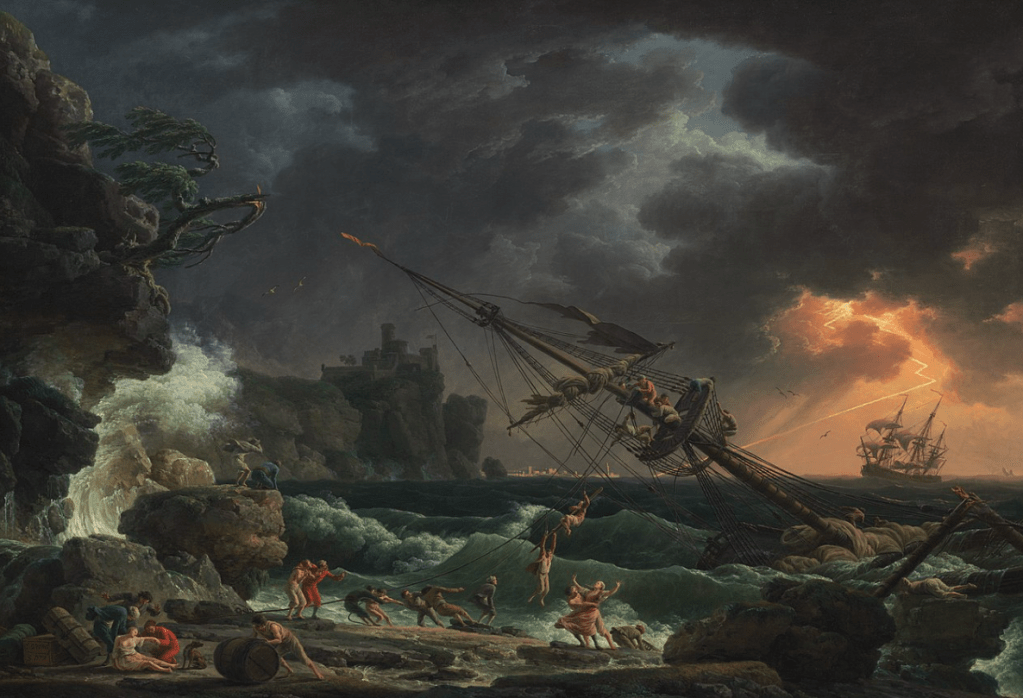

Clearly, Captain Palmer believed speed was essential, and was determined to get to Cadiz in the shortest possible time. As it turned out, his impatience would reap terrible consequences, both for his crew and himself. By midnight, storm conditions had developed, and visibility, obscured by freezing rain, became a serious problem. Around three o’clock in the morning, the watches spotted an island about a mile ahead of the Nautilus, which was believed to be Cerigotto. Captain Palmer, now convinced that he was out of danger, went below to consult his charts. He and everyone else awake were then jolted by cries of “Breakers ahead! Breakers ahead!” The Nautilus smashed into the rocks. The shock was tremendous, and flung some of the men sleeping below from their racks. Boone describes the scene:

[S]uch was the violence of the shock, that the writer of these pages was thrown from his bed, and was unable to stand upon deck without holding. It is impossible to describe the feelings which predominated, at a moment so distressing. Hope, fear, and despair, by turns prevailed. The greater part of our crew immediately hurried upon deck; before all reached it, the ladders gave way, and left many poor wretches struggling in the water, which had already rushed in torrents into the ship. Upon deck all was confusion and alarm; when we had clearly ascertained our situation, we could not but consider our destruction as inevitable.

Luckily the Nautilus was possessed of a very good executive officer, one Lieutenant Alexander Nesbitt, who took charge of the chaotic situation. But the ship was stuck on the rocks, and as the stormy waves dashed against her hull, she began to break apart. Nesbitt ordered life boats to be launched, but only one small whaleboat managed to escape the wreck; the others either capsized in the storm or were unable to move. The one boat that escaped the wreck, piloted by a coxswain named George Smith, took aboard as many men as it could, and rowed towards the island of Pauri. Under the circumstances, there was nothing else they could do; their best course of action was to reach a population center and request help for their comrades.

Meanwhile, the Nautilus continued to break apart. The men left aboard were forced to evacuate the ship and huddle together, battered by freezing surf and rain, on a tiny shoal of rock perched just barely above the waves. The ledge was between three hundred and four hundred yards in length, and only about two hundred yards in width. Nearly a hundred men now occupied this miserable, slippery, freezing speck of reef. Most of them were without adequate clothing or shoes. As they huddled there, shivering, they could hear the splitting roars of the Nautilus’s timbers as they broke apart amid the fury of the waves.

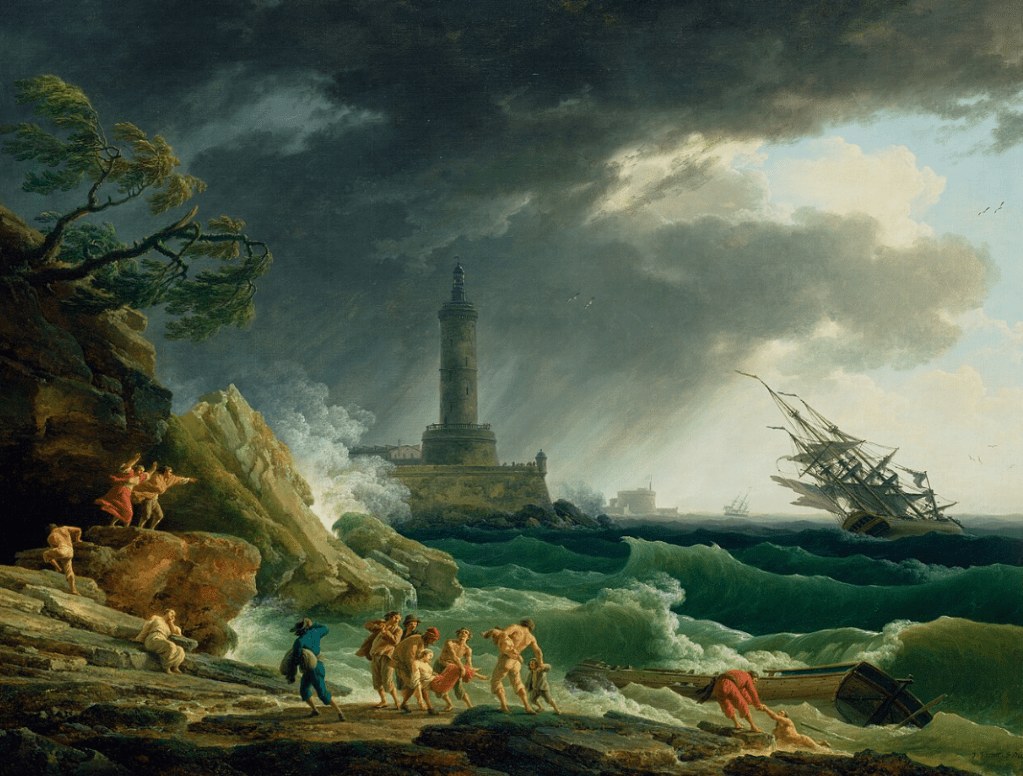

As dawn came, the men were greeted by fresh horrors. Around them in the sea were visible the floating corpses of some of their dead comrades, mixed in with bits and pieces of the Nautilus’s wreckage. The men estimated that they were at least twelve miles from the nearest land. They flew a distress flag in the hope of attracting a passing vessel, but it was clear that their only real hope was that coxswain George Smith would return with local boats to rescue them. One of the men luckily had a knife and flint; with this they were able to build a fire. A tent was constructed with salvaged canvas and poles from the ship. Most distressing of all was the fact that the men had no food or water of any kind. Soon they began to experience the torments of thirst and hunger.

George Smith did in fact manage to reach Pauri. But there he found very little besides impoverished Greeks and a few sheep and goats. Smith and his party rowed back to the men stranded on the reef, and were shocked by the desperate condition of their shipmates. Smith spoke to Captain Palmer, who was among the stranded, and offered to take him aboard; to his credit, Palmer chose to remain with his men. He told Smith to take ten more men from the reef, and make for the island of Cerigo (Kythira), where there might be a better chance of finding a population center. After Smith departed in the whaleboat, the waves rose and began to lash the exposed men on the reef with merciless ferocity. They had no fire, no way of catching food, and, worst of all, no water. Many men perished of exposure and thirst. Boone describes one tragic incident with fearsome vividness:

It will appear, perhaps, almost incredible, that we could have sustained the many hardships we had already gone through. One poor fellow, in crossing the channel between the rocks at an improper time, was violently dashed against the craggs, so as to be nearly scalped, and presented a dreadful object to our view—he lingered during the night, and the next morning expired. His more fortunate survivors were but ill prepared to meet the terrible effects of famine; our strength was exhausted, our bodies without covering, and hope had almost left us. We had great fears too for the safety of our little boat: she might be lost, as the storm came on before it was possible she could have reached the island. It is a great and merciful God alone, that we have to thank for our preservation. And the afflicting scenes which the next morning presented, render our deliverance from total destruction, almost miraculous.

The men on the shoal could do nothing except try to survive the waves while praying for George Smith to return with a rescue party. There then occurred an event so heartbreaking, and heartless, that it might hardly be believed, were it not confirmed by the testimonial record of the Nautilus affair. “I have now to relate,” says Boone, “an instance of the most cruel inhumanity—of inhumanity, I should hope for the honor of mankind, unparalleled.” The men spotted a full-rigged ship approach their shoal; the ship, of indeterminate nationality, clearly saw the stranded men, and launched a boat to investigate. The Nautilus crewmen were overjoyed at the imminent prospect of their rescue. But it was not to be: the rowboat, filled with men in European dress, suddenly paused as it approached the shoal, then turned around and went back to the ship. The vessel had clearly seen them, but sailed away without making contact with the men.

This cruel incident brought the men of the Nautilus to the brink of despair. Some of the men, no longer able to restrain their thirst, drank seawater and quickly became howling madmen. Then George Smith returned, carrying earthen jars of water; but the jars could not be brought on the shoal, as the sea was too rough. He did inform the desperate survivors that a rescue ship was on the way, and should arrive at any time. But no rescue came, and another day passed. The men now resorted to cannibalism; one corpse was cut up, but the men were so parched by thirst that they could not even masticate the grisly meal. Around this time, Captain Palmer perished from exposure and thirst.

Some of the men decided to try and build a raft, surmising that it was better to die at sea than to wait for hunger and thirst to claim them on the rocks. Those who entered the water on these makeshift rafts saw them dashed to pieces immediately by the waves; the men were swept away by the currents and drowned. George Smith returned again on this whaleboat, and told the survivors that he had managed to convince some Greek fishermen to come to their rescue once the stormy seas had subsided. After five full days on the rocks with no food or drink, rescue came on the morning of the sixth day. Greek boats arrived with food and water, and brought them to the island of Cerigotto (Antikythira). Boone describes the island:

We found Cerigotto, an island belonging to the dependency of Cerigo, inhabited by twelve or fourteen families of fishermen. It may be about fifteen miles long, and ten broad; its soil appears barren and uncultivated. The inhabitants are in the lowest state of poverty and wretchedness, their huts are built generally against the rock, and consist of one or two rooms on the same floor, the walls are clay and straw, and the roof is supported by a tree, which is placed in the centre of the dwelling; their food indicates extreme poverty, being a coarse kind of bread made from boiled pease [sic] and flour, this, with occasionally a bit of kid, was all the Greek fishermen, our deliverers, could offer us. They drink a strong liquor made from corn, the flavour of which is agreeable, and from its strength, our sailors drank it with great avidity.

Of the 122 men who had been stranded on the rocks, only 64 survived; the rest were taken by hunger, thirst, or the sea. The survivors spent eleven days at Cerigotto in recuperation, then sailed to Malta. A court-martial conducted at Cadiz found Captain Palmer’s haste a proximate cause of the wreck, but had warm words for the actions of Lieutenant Nesbitt. The inquest found that “Lieutenant Nesbitt and the officers and crew did use every exertion that circumstances should dictate.” As so often happens in the fateful annals of conflict and exploration, folly and heroism are mixed in equal portions; and what is wrought by the former is hopefully tempered by the latter.

.

.

Take a look at the new, annotated translation of Cicero’s On The Nature Of The Gods.

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.