Of the German explorers of the eighteenth century, the only man whose accomplishments rival those of Alexander von Humboldt is Carsten Niebuhr. His extensive travels and surveys in the Near East and India resulted in specific geographical data, surveying information, and historical insights. This was no dreamy wanderer; this was a trained professional, a man who was tough, hard-bitten, and practical, with the astuteness to process what was going on around him and commit his observations faithfully to paper.

If he is little-known today–as are so many of these great explorers we have enshrined here–the fault lies with us, not with him; for as the sole survivor of the so-called “Danish-Arabian Expedition,” he proved himself not only as a scientist, but as a tenacious fighter. His origins were modest, as are those of many great explorers. He was born in 1733 in Lower Saxony to an agrarian family. Access to education for him was not easy, but he did learn the value of hard physical labor; perhaps it was these early years before the plow that forged the iron constitution his body would display in future travels. He did show an aptitude for surveying and map-reading, and as he grew to adulthood his services were sought by local notables in the area.

The mid-eighteenth century was a period of religious revival in Europe as well as in the American colonies; there was a hunger for accurate and modern information on the regions described in the Bible. The Ottoman sultans were in general favorably disposed towards permitting foreigners access to their domains, as long as they secured permission in advance. Motivated crowned heads in Europe did not take long to respond to such windows of opportunity.

Through one of his colleagues, Niebuhr received word that Frederik V of Denmark was assembling an expedition to Arabia, Syria, Egypt, and other parts of the Near East. The subtle Danish king prided himself on being a patron of the arts and sciences, and was determined to expand the outer limits of the current knowledge of the Middle East. Having nothing else to do, Niebuhr resolved to apply for the position of surveyor. In preparation, he polished his skills at the University of Goettingen, and applied himself to the study of the Arabic language. He would never achieve the dazzling proficiency in Arabic that we find in John Lewis Burckhardt or Richard Burton; but Niebuhr was good enough, and he more than made up any shortcomings in this area with other equally important skills.

By 1760 the members of the expedition had been chosen. They were: Peter Forsskål, a Swedish naturalist; Frederik Christian von Haven, a Danish linguist and philologist; Niebuhr himself, who would act as surveyor and geographer; Christian Carl Kramer, a Danish physician; Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind, a painter and artist (in the days before photography, artists were part of every well-equipped expedition); and Lars Berggren, a Swedish soldier and orderly. Frederik’s instructions to his men were to “make as many scientific discoveries as possible,” and, most importantly, to refrain from any conduct that might arouse the antagonism of the “native Mohammedans.” In other words, they were to act in a modest, humble manner, and not as arrogant imperialists or conquerors.

The expedition left Europe in January 1761, and made for Alexandria, Egypt. From here the team traveled to Suez, then Jeddah in Arabia, and then into Yemen (Hadramaut), which was at that time was a very remote corner of the Arab world. But disaster struck in Yemen; two members of the expedition died in May 1763 (von Haven and Forsskål), probably from malaria, although the record is not entirely clear. We must understand that Europeans at that time did not appreciate the need to adopt local clothing and mannerisms. In addition, modern knowledge of vitamin deficiency diseases, dehydration, and malnutrition were entirely lacking.

Among the team members, only Niebuhr seemed to thrive. He was a tough, lean German of peasant stock who was used to physical privation. More importantly, however, he had the humility and canniness to watch how the Arabs dressed and conducted themselves in the desert, and quickly set about imitating them. This amused the locals, of course; but the bedouins respected him, and gave him an extensive wardrobe of native garb, as well as foods more suited to the climate, such as dates, dried meats, and thick cheeses. Niebuhr’s account of his travels was translated from German into English in the early 1790s. It makes for interesting reading today, as it contains a wealth of personal observations that scrupulously strive for objectivity despite the obfuscating fogs of cultural conditioning. Here he describes some social habits of his hosts:

The Arabs are not quarrelsome; but, when any dispute happens to arise among them, they make a great deal of noise. I have seen some of them, however, who, although armed with poignards, and ready to stab one another, were easily appeased. A reconciliation was instantly effected, if any indifferent person but said to them, Think of God and his Prophet. When the contest could not be settled at once, umpires were chosen, to whose decision they submitted. The inhabitants of the East in general strive to master their anger.

A boatman of Muscat complained to the governor of the city of a merchant who would not pay a freight due for the carriage of his goods. The governor always put off hearing him, till some other time. At last the plaintiff told his case coolly, and the governor immediately did him justice, saying, I refused to hear you before, because you were intoxicated with anger, the most dangerous of all intoxications. Notwithstanding this coolness, on which the people of the East pique themselves, the Arabs shew great sensibility to every thing that can be construed into an injury. If one man should happen to spit beside another, the latter will not fail to avenge himself of the imaginary insult.

In a caravan I once saw an Arab highly offended at a man, who, in spitting, had accidentally bespattered his beard with some small part of the spittle. It was with difficulty that he could be appeased by him, who, he imagined, had offended him, even although he humbly asked pardon, and kissed his beard in token of submission. They are less ready to be offended by reproachful language, which is, besides, more in use with the lower people than among the higher classes. [Heron, p. 198]

Here Niebuhr describes the basic dress of the region:

The ordinary dress of the Arabs is indeed simple enough; but they have also a sort of great-coat, without sleeves, called Abba, which is simpler still. I was acquainted with a blind taylor at Basra [in Iraq], who earned his bread by making Abbas; so that they cannot be of a very nice shape, or made of many pieces; In Yemen they are worn only by travellers; but in the province of Lachsa, the Abba is a piece of dress commonly used by both sexes. [Heron, p. 235]

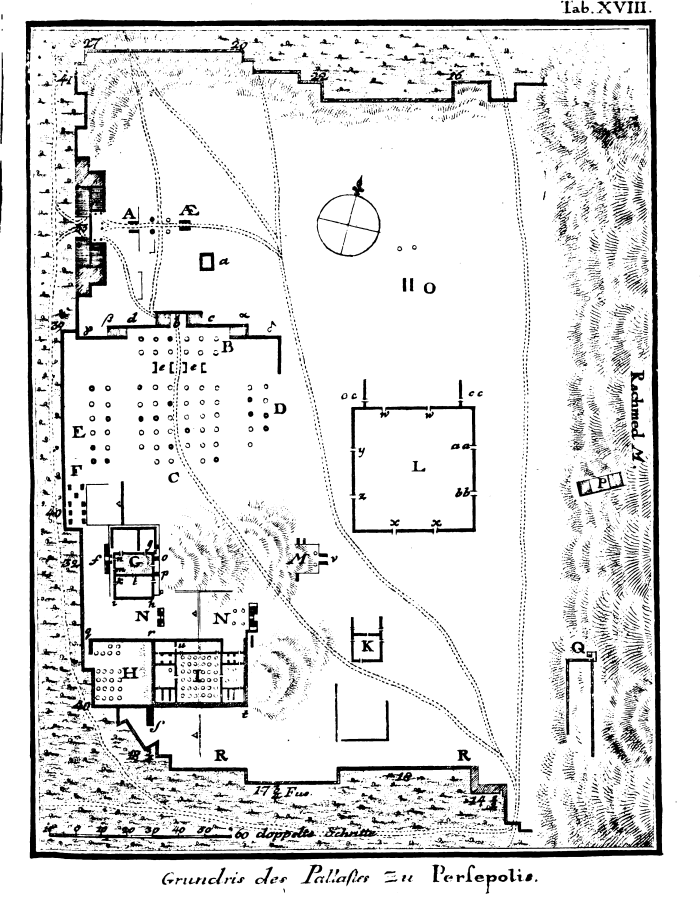

The expedition next sailed from Yemen to Bombay. En route, two more members died (Georg Baurenfeind and Lars Berggren); and once the ship reached India, the physician, Kramer, also died, leaving Niebuhr now completely alone. It was a similar situation that African explorer Heinrich von Barth would encounter in later decades. Niebuhr decided to press on, oblivious to the hardships and determined to carry out the commission entrusted to him by the Danish king. After spending a little over a year in Bombay in preparation, he traveled overland through Persia, then what is now Iraq, Syria, and Palestine, Cyprus, and Israel. He transcribed the famous “Behistun Inscription” in 1764 (which helped pave the way for the later decipherment of cuneiform script), and finally reached Constantinople in February 1767.

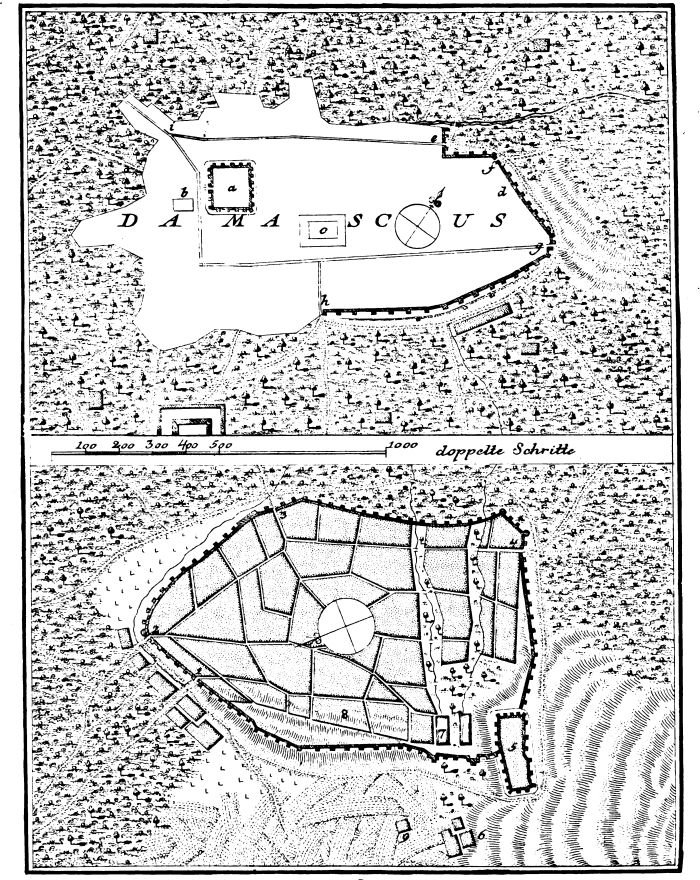

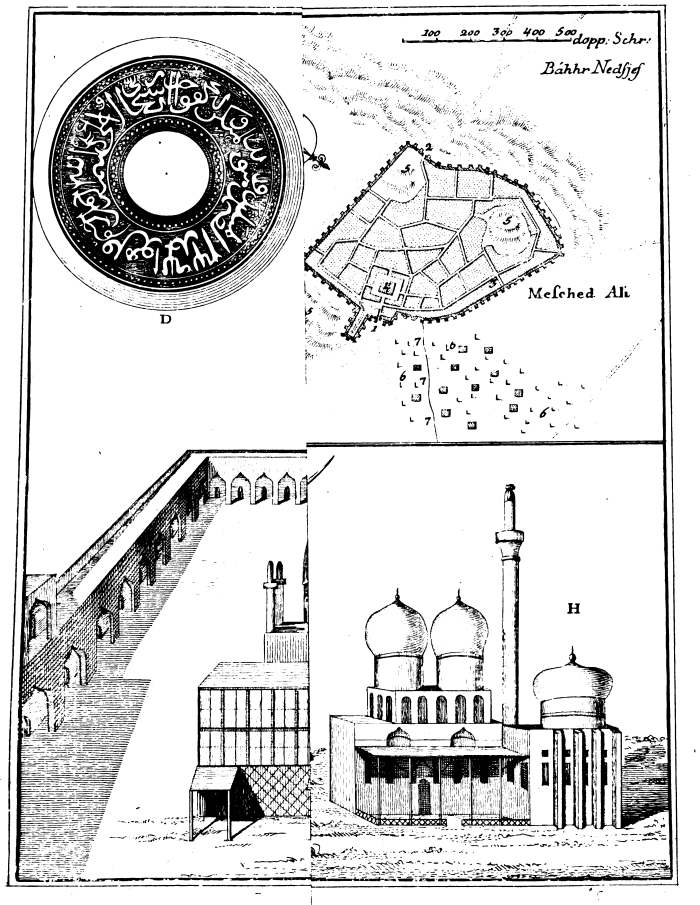

From here he sailed back to Copenhagen in triumph; it had been an incredible odyssey, exceeded in romantic danger only by its practical utility. Rarely has one man’s travel yielded so much in practical detail; Niebuhr’s maps are masterpieces of utility, and were used for generations. Plant and animal specimens, as well as Arabic and Persian manuscripts, were also brought back and are still used to this day. His explorations also provided precious ethnographic and historical information for later scholars. Before they died, the other members of the team did their jobs wonderfully, and Niebuhr (in contrast to the behavior of some later explorers) was careful to give them the credit that they deserved.

Of Niebuhr’s absolute dedication to scholarship there can be no question. Not only did he risk his life (and devote ten years of it) during the expedition, but he was forced to commit his personal resources to ensure that his books and maps found print. As often happens in such situations, royal interest in the expedition waned quickly after Niebuhr returned to Copenhagen. The government was willing to finance his efforts from that point only grudgingly. The voluminous output of his findings stretched into six volumes, most of which Niebuhr had to pay for himself. And yet it was all worth it: all the suffering, all the financial expenditure, and the lives of the men who had been lost. For here, for the first time, was hard, tangible information about the Arabic-speaking regions of the East, as well as antiquarian data on the ruins that dotted western Persia. All later travelers would stand on the shoulders of their achievements. Niebuhr died in the city of Meldorf in 1815 at the age of 82.

All in all, the Danish-Arabian expedition was a triumph of Enlightenment faith in science and observation, wedded with iron determination, luck, and sustained effort. It was imbued with a spirit of genuine curiosity and scientific objectivity; and there was not a shred of the cultural friction that has too often marred the record of European contact with the region. To this day, it remains perhaps the most productive expedition to the Middle East ever carried out.

Read Sallust today in this groundbreaking annotated edition, with maps, background information, diagrams, and much more:

You must be logged in to post a comment.