Some months ago The Guardian published an article about the reopening of a reconstructed mithraeum (Temple of Mithras) in London. I had known about the cult of Mithras for some time; the Roman emperor Julian, whom I have written about, was a devoted follower of the religion. Yet it remains almost totally unknown to the public, even to students of classical literature and ancient history. It will be useful to review its origins, doctrines, and the reasons for its extinction.

It was an eastern (“oriental”) faith of Persian origin. The god Mithras originally belonged to that complex pantheon of deities that can be found in the remote pasts of Persia and India. India, that eternal wellspring of religious faiths, was the ultimate source of Mithraism; the name “Mithra” appears in both the Vedas and the Avesta. Mithra (or “Mitra-Varuna”) was held to be a god of light, a protector of truth and a deliverer from error. The worship of Mithra gradually percolated into Persia, where it became incorporated into Zoroastrianism and was assigned a position in that religion’s cosmology. Mithra occupied an intermediary place between the most elevated god Oromazes and the ruler of the realm of darkness Ahriman. From the beginning, the god was attended by a complicated series of rituals and ceremonial initiations, a feature that Mithraism would retain as it moved westward into the Greco-Roman world.

The Greeks had a long tradition of contact with Persia and its customs, and it was only natural that aspects of that culture would begin to be felt in Europe. The primary means of dissemination of the cult of Mithra was through the military; Greek or Roman soldiers serving in the East came into contact with this strange “mystery” religion, were attracted by its rituals and masculine hierarchies, and brought it back home with them. As historian Franz Cumont writes, in his The Mysteries of Mithra, “The contact of all the theologies of the Orient and all the philosophies of Greece produced the most startling combinations, and the competition between the different creeds became exceedingly brisk.”

Over time, the pure Mithraism of India and Persia became blended and changed by Grecian and Roman elements; it added a strong Neoplatonic flavor, as well as Syriac and Assyrian colorings. It was also heavily influenced by Stoicism, as Cumont explains:

Mysteries might possess for minds formed in the schools of Greece; philosophy also strove to reconcile their doctrines with its teachings, or rather the Asiatic priests pretended to discover in their sacred traditions the theories of the philosophic sects. None of these sects so readily lent itself to alliance with the popular devotion as that of the Stoa, and its influence on the formation of Mithraism was profound. An ancient myth sung by the Magi is quoted by Dion Chrysostomos on account of its allegorical resemblance to the Stoic cosmology; and many other Persian ideas were similarly modified by the pantheistic conceptions of the disciples of Zeno.

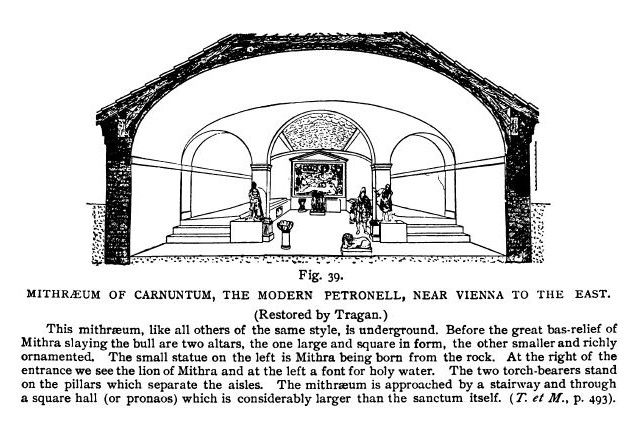

Since Mithraism tended to be a masculine religion, its practice took on the flavor of a secret society, with windowless temples dug into the earth, along with secret rituals that could only be revealed to initiates. Mithraism was combination of a Persian core mixed with Semitic rituals and adorned with Hellenic philosophical trappings in the form of Neoplatonism. This should not surprise us; all religions are in some ways composites of the environment from which they have evolved. With Roman expansion into Asia, the faith spread; the poet Statius mentions it in his Thebiad (I.717): Persei sub rupibus antri Indignata sequi torquentem cornua Mithram. It was a religion of soldiers, for its doctrines appealed to the masculine beliefs in sacrifice, redemption, and the acquisition of knowledge. Soldiers, like sailors, tend to be pious and superstitious, since so much of their lives depend on geography, the elements, and the randomness of fate.

What were the doctrines of this faith, the so-called “mysteries”? Because of its secret nature, we still to this day do not have a precise liturgy of Mithraism. It worshipped the four elements earth, air, fire, and water, and produced hymns in honor of the creative power of these elements. But the most potent of Mithraism’s rituals was that surrounding the bull, a fertility symbol dating back to the dawn of history itself. Ancient man venerated the bull as a source of food, fertility, and the power of nature itself. The importance of the bull to the worship of Mithra is explained by scholar Franz Cumont:

In the eyes of [ancient man], the capture of a wild bull was an achievement so highly fraught with honor as to be apparently no derogation even for a god. The redoubtable bull was grazing in a pasture on the mountain-side; the hero, resorting to a bold stratagem, seized it by the horns and succeeded in mounting it. The infuriated quadruped, breaking into a gallop, struggled in vain to free itself from its rider; the latter, although unseated by the bull’s mad rush, never for a moment relaxed his hold; he suffered himself to be dragged along, suspended from the horns of the animal, which, finally exhausted by its efforts, was forced to surrender.

Its conqueror then seizing it by its hind hoofs, dragged it backwards over a road strewn with obstacles into the cave which served as his home. This painful journey (transitus) of Mithra became the symbol of human sufferings. But the bull, it would appear, succeeded in making its escape from its prison, and roamed again at large over the mountain pastures. The Sun then sent the raven, his messenger, to carry to his ally the command to slay the fugitive. Mithra received this cruel mission much against his will, but submitting to the decree of Heaven he pursued the truant beast with his agile dog, succeeded in overtaking it just at the moment when it was taking refuge in the cave which it had quitted, and seizing it by the nostrils with one hand, with the other he plunged deep into its flank his hunting knife.

Then came an extraordinary prodigy to pass. From the body of the moribund victim sprang all the useful herbs and plants that cover the earth with their verdure. From the spinal cord of the animal sprang the wheat that gives us our bread, and from its blood the vine that produces the sacred drink of the Mysteries….

The seed of the bull, gathered and purified by the Moon, produced all the different species of useful animals, and its soul, under the protection of the dog, the faithful companion of Mithra, ascended into the celestial spheres above, where, receiving the honors of divinity, it became under the name of Silvanus the guardian of herds. Thus, through the sacrifice which he had so resignedly undertaken, the tauroctonous hero became the creator of all the beneficent beings on earth; and, from the death which he had caused, was born a new life, more rich and more fecund than the old.

This is the origin of the bull-sacrifice motif in Mithraism. Life is presented as a battle, and the continuation of life is dependent on sacrifice and struggle. The religion counseled resistance to carnal delights and sexual indulgence; this asceticism was probably a relic of its early Stoic influences. Mithraism also elevated dynamic action over passive contemplation, and courage over mercy. Good and evil were in constant tension with each other, its adherents believed, and only by constantly emphasizing good would a man be able to overcome the forces of darkness. This ethical code accounted for much of Mithraism’s success.

The new religion was remarkable in that it was able to adapt itself to a wide variety of environments and locales. There was a real possibility that it might have become the dominant religion of the Empire and of Europe. Temples to Mithras (mithraea) have been found all over the former Roman domains. Why, then, did the religion die out? Simply put, it could not compete with the spread of Christianity, which doomed many other Oriental cults of late antiquity (the cults of Adonis, Serapis, and Isis to name the most prominent).

Mithraism did not proselytize; and by forbidding women any role in the faith, it deprived itself of an incalculable source of potential power. Perhaps, too, Mithraism was too burdened with the weight of weird Indian and Persian gods that would have been bizarre to Roman, Greek, or Germanic sensibilities. It also must be said that Christianity persecuted all rival religions with a ferocity that was unmatched: mobs sacked temples to Mithras, slew Mithraic priests, and suppressed its liturgy on pain of physical retribution.

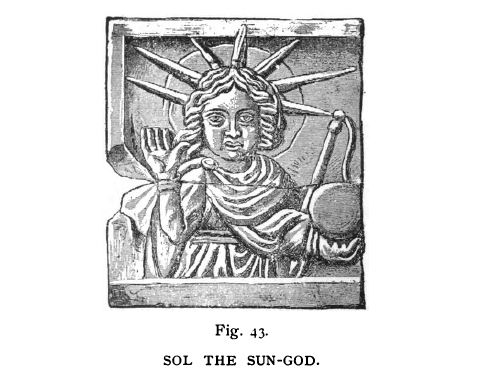

Yet the influence of Mithraism is undeniable. Consider, for example this illustration of Sol invictus, the invincible Sun God of the Mithraic cosmology, which is found in Franz Cumont’s 1903 study of Mithraism. It looks uncannily like the American Statue of Liberty in New York City, and must have had some substratal influence in its design:

In history, nothing is ever really forgotten. A religion may die; but its art, ethic, and soul endure, in whatever incarnation human genius and sensibility see fit to generate.

Read the newest, most innovative translation of Sallust today:

You must be logged in to post a comment.